Longtermism: a call to protect future generations

Benjamin Inouye, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

When the 19th-century amateur scientist Eunice Newton Foote filled glass cylinders with different gases and exposed them to sunlight, she uncovered a curious fact. Carbon dioxide became hotter than regular air and took longer to cool down.1

Remarkably, Foote saw what this momentous discovery meant.

“An atmosphere of that gas would give our earth a high temperature,” she wrote in 1857.2

Though Foote could hardly have been aware at the time, the potential for global warming due to carbon dioxide would have massive implications for the generations that came after her.

If we ran history over again from that moment, we might hope that this key discovery about carbon’s role in the atmosphere would inform governments’ and industries’ choices in the coming century. They probably shouldn’t have avoided carbon emissions altogether, but they could have prioritised the development of alternatives to fossil fuels much sooner in the 20th century, and we might have prevented much of the destructive climate change that present people are already beginning to live through — which will affect future generations as well.

We believe it would’ve been much better if previous generations had acted on Foote’s discovery, especially by the 1970s, when climate models were beginning to reliably show the future course of warming global trends.3

If this seems right, it’s because of a commonsense idea: to the extent that we are able to, we have strong reasons to consider the interests and promote the welfare of future generations.

That was true in the 1850s, it was true in the 1970s, and it’s true now.

But despite the intuitive appeal of this moral idea, its implications have been underexplored. For instance, if we care about generations 100 years in the future, it’s not clear why we should stop there.

And when we consider how many future generations there might be, and how much better the future could go if we make good decisions in the present, our descendants’ chances to flourish take on great importance. In particular, we think this idea suggests that improving the prospects for

This article will lay out the argument for this view, which goes by the name longtermism.

We’ll say where we think the argument is strongest and weakest, respond to common objections, and say a bit about what we think this all means for what we should do.

Table of Contents

The case for longtermism

While most recognize that future generations matter morally to some degree, there are two other key premises in the case for longtermism that we believe are true and underappreciated. All together, the premises are:

- We should care about how the lives of future individuals go.

- The number of future individuals whose lives matter could be

vast . - We have an opportunity to affect how the long-run future goes — whether there may be many flourishing individuals in the future, many suffering individuals in the future, or perhaps no one at all.4

In the rest of this article, we’ll explain and defend each of these premises. Because the stakes are so high, this argument suggests that improving the prospects for all future generations should be a top moral priority of our time. If we’re able to make an exceptionally big impact, positively influencing many lives with enduring consequences, it’s incumbent upon us to take this seriously.

This doesn’t mean it’s the only morally important thing — or that the interests of future generations matter to the total exclusion of the present generation. We disagree with both of those claims.

There’s also a good chance this argument is flawed in some way, so much of this article discusses objections to longtermism. While we don’t find them on the whole convincing, some of them do reduce our confidence in the argument in significant ways.

If we’re able to make an exceptionally big impact, positively influencing many lives with enduring consequences, it’s incumbent upon us to take this seriously.

However, we think it’s clear that our society generally neglects the interests of future generations. Philosopher Toby Ord, an advisor to 80,000 Hours, has argued that at least by some measures, the world spends more money on ice cream each year than it does on reducing the risks to future generations.5

Since, as we believe, the argument for longtermism is generally compelling, we should do a lot more compared to the status quo to make sure the future goes well rather than badly.

It’s also crucial to recognise that longtermism by itself doesn’t say anything about how best to help the future in practice, and this is a nascent area of research. Longtermism is often confused with the idea that we should do more long-term planning. But we think the primary upshot is that it makes it more important to urgently address extinction risks in the present — such as catastrophic pandemics, an AI disaster, nuclear war, or extreme climate change. We discuss the possible implications in the final section.

But first, why do we think the three premises above are true?

1. We should care about how the lives of future individuals go

Should we actually care about people who don’t exist yet?

The discussion of climate change in the introduction is meant to draw out the common intuition that we do have reason to care about future generations. But sometimes, especially when considering the implications of longtermism, people doubt that future generations matter at all.

Derek Parfit, an influential moral philosopher, offered a simple thought experiment to illustrate why it’s plausible that future people matter:

Suppose that I leave some broken glass in the undergrowth of a wood. A hundred years later this glass wounds a child. My act harms this child. If I had safely buried the glass, this child would have walked through the wood unharmed.

Does it make a moral difference that the child whom I harm does not now exist?6

We agree it would be wrong to dispose of broken glass in a way that is likely to harm someone. It’s still wrong if the harm is unlikely to occur until 5 or 10 years have passed — or in another century, to someone who isn’t born yet. And if someone else happens to be walking along the same path, they too would have good reason to pick up the glass and protect any child who might get harmed at any point in the future.

But Parfit also saw that thinking about these issues raised surprisingly tricky philosophical questions, some of which have yet to be answered satisfactorily. One central issue is called the ‘non-identity problem’, which we’ll discuss in the objections section below. However, these issues can get complex and technical, and not everyone will be interested in reading through the details.

Despite these puzzles, there are many cases similar to Parfit’s example of the broken glass in the woods in which it’s clearly right to care about the lives of future people. For instance, parents-to-be rightly make plans based around the interests of their future children even prior to conception. Governments are correct to plan for the coming generations not yet born. And if it is reasonably within our power to prevent a totalitarian regime from arising 100 years from now,7 or to avoid using up resources our descendants may depend on, then we ought to do so.

While longtermism may seem to some like abstract, obscure philosophy, it in fact would be much more bizarre and contrary to common sense to believe we shouldn’t care about people who don’t yet exist.

2. The number of future individuals whose lives matter could be vast.

Humans have been around for hundreds of thousands of years. It seems like we could persist in some form for at least a few hundred thousand more.

There is, though, serious risk that we’ll cause ourselves to go extinct — as we’ll discuss more below. But absent that, humans have proven that they are extremely inventive and resilient. We survive in a wide range of circumstances, due in part to our ability to use technology to adjust our bodies and our environments as needed.

How long can we reasonably expect the human species to survive?

That’s harder to say. More than 99 percent of Earth’s species have gone extinct over the planet’s lifetime,8 often within a few million years or less.9

It’s possible our own inventiveness could prove to be our downfall.

But if you look around, it seems clear humans aren’t the average Earth species. It’s not ‘speciesist’ — unfairly discriminatory on the basis of species membership — to say that humans have achieved remarkable feats for an animal: conquering many diseases through invention, spreading across the globe and even into orbit, expanding our life expectancy, and splitting the atom.

It’s possible our own inventiveness could prove to be our downfall. But if we avoid that fate, our intelligence may let us navigate the challenges that typically bring species to their ends.

For example, we may be able to detect and deflect comets and asteroids, which have been implicated in past mass extinction events.

If we can forestall extinction indefinitely, we may be able to thrive on Earth for as long as it’s habitable — which could be another 500 million years, perhaps more.

As of now, there are about 8 billion humans alive. In total, there have been around 100 billion humans who ever lived. If we survive to the end of Earth’s habitable period, all those who have existed so far will have been the first raindrops in a hurricane.

If we’re just asking about what seems possible for the future population of humanity, the numbers are breathtakingly large. Assuming for simplicity that there will be 8 billion people for each century of the next 500 million years,10 our total population would be on the order of forty quadrillion. We think this clearly demonstrates the importance of the long-run future.

And even that might not be the end. While it remains speculative, space settlement may point the way toward outliving our time on planet Earth.11 And once we’re no longer planet-bound, the potential number of people worth caring about really starts getting big.

In What We Owe the Future, philosopher and 80,000 Hours co-founder Will MacAskill wrote:

…if humanity ultimately takes to the stars, the timescales become literally astronomical. The sun will keep burning for five billion years; the last conventional star formations will occur in over a trillion years; and, due to a small but steady stream of collisions between brown dwarfs, a few stars will still shine a million trillion years from now.

The real possibility that civilisation will last such a long time gives humanity an enormous life expectancy.

Some of this discussion may sound speculative and fantastical — which it is! But if you consider how fantastical our lives and world would seem to humans 100,000 years ago, you should expect that the far future could seem at least as alien to us now.

And it’s important not to get bogged down in the exact numbers. What matters is that there’s a reasonable possibility that the future is very long, and it could contain a much greater number of individuals.12 So how it goes could matter enormously.

There’s another factor that expands the scope of our moral concern for the future even further. Should we care about individuals who aren’t even human?

It seems true to us that the lives of non-human animals in the present day matter morally — which is why factory farming, in which billions of farmed animals suffer every day, is such a moral disaster.13 The suffering and wellbeing of future non-human animals matters no less.

And if the far-future descendants of humanity evolve into a different species, we should probably care about their wellbeing as well. We think we should even potentially care about possible digital beings in the future, as long as they meet the criteria for moral patienthood — such as, for example, being able to feel pleasure and pain.

We’re highly uncertain about what kinds of beings will inhabit the future, but we think humanity and its descendants have the potential to play a huge role. And we want to have a wide scope of moral concern to encompass all those for whom life can go well or badly.14

When we think about the possible scale of the future ahead of us, we feel humbled. But we also believe these possibilities present a gigantic opportunity to have a positive impact for those of us who have appeared so early in this story.

The immense stakes involved strongly suggest that, if there’s something we can do to have a significant and predictably positive impact on the future, we have good reason to try.

Arnold Paul, CC BY-SA 2.5 (cropped)

Arnold Paul, CC BY-SA 2.5 (cropped)3. We have an opportunity to affect how the long-run future goes

When Foote discovered the mechanism of climate change, she couldn’t have foreseen how the future demand for fossil fuels would trigger a consequential global rise in temperatures.

So even if we have good reason to care about how the future unfolds, and we acknowledge that the future could contain immense numbers of individuals whose lives matter morally, we might still wonder: can anyone actually do anything to improve the prospects of the coming generations?

It’d be better for the future if we avoid extinction, manage our resources carefully, foster institutions that promote cooperation rather than violent conflict, and responsibly develop powerful technology.

Many things we do affect the future in some way. If you have a child or contribute to compounding economic growth, the effects of these actions ripple out over time, and to some extent, change the course of history. But these effects are very hard to assess. The question is whether we can predictably have a positive impact over the long term.

We think we can. For example, we believe that it’d be better for the future if we avoid extinction, manage our resources carefully, foster institutions that promote cooperation rather than violent conflict, and responsibly develop powerful technology.

We’re never going to be totally sure our decisions are for the best — but often we have to make decisions under uncertainty, whether we’re thinking about the long-term future or not. And we think there are reasons to be optimistic about our ability to make a positive difference.

The following subsections discuss four primary approaches to improving the long-run future:

Reducing extinction risk

One plausible tactic for improving the prospects of future generations is to increase the chance that they get to exist at all.

Of course, if there was a nuclear war or an asteroid that ended civilization, most people would agree that it was an unparalleled calamity.

Longtermism suggests, though, that the stakes involved could be even higher than they first seem. Sudden human extinction wouldn’t just end the lives of the billions currently alive — it would cut off the entire potential of our species. As the previous section discussed, this would represent an enormous loss.

And it seems plausible that at least some people can meaningfully reduce the risks of extinction. We can, for example, create safeguards to reduce the risk of accidental launches of nuclear weapons, which might trigger a cataclysmic escalatory cycle that brings on nuclear winter. And NASA has been testing technology to potentially deflect large near-Earth objects on dangerous trajectories.15 Our efforts to detect asteroids that could pose an extinction threat have arguably already proven extremely cost-effective.

So if it’s true that reducing the risk of extinction is possible, then people today can plausibly have a far-reaching impact on the long-run future. At 80,000 Hours, our current understanding is that the biggest risks of extinction we face come from advanced artificial intelligence, nuclear war, and engineered pandemics.16

And there are real things we can do to reduce these risks, such as:

- Developing broad-spectrum vaccines that protect against a wide range of pandemic pathogens

- Enacting policies that restrict dangerous practices in biomedical research

- Inventing more effective personal protective equipment

- Increasing our knowledge of the internal workings of AI systems, to better understand when and if they could pose a threat

- Technical innovations to ensure that AI systems behave how we want them to

- Increasing oversight of private development of AI technology

- Facilitating cooperation between powerful nations to reduce threats from nuclear war, AI, and pandemics.

We will never know with certainty how effective any given approach has been in reducing the risk of extinction, since you can’t run a randomised controlled trial with the end of the world. But the expected value of these interventions can still be quite high, even with significant uncertainty.17

One response to the importance of reducing extinction risk is to note that it’s only positive if the future is more likely to be good than bad on balance. That brings us onto the next way to help improve the prospects of future generations.

Positive trajectory changes

Preventing humanity’s extinction is perhaps the clearest way to have a long-term impact, but other possibilities may be available. If we’re able to take actions that influence whether our future is full of value or is comparatively bad, we would have the opportunity to make an extremely big difference from a longtermist perspective. We can call these trajectory changes.18

Climate change, for example, could potentially cause a devastating trajectory shift. Even if we believe it probably won’t lead to humanity’s extinction, extreme climate change could radically reshape civilisation for the worse, possibly curtailing our viable opportunities to thrive over the long term.

There might even be potential trajectories that could be even worse. For example, humanity might get stuck with a value system that undermines general wellbeing and may lead to vast amounts of unnecessary suffering.

How could this happen? One way this kind of value ‘lock-in’ could occur is if a totalitarian regime establishes itself as a world government and uses advanced technology to sustain its rule indefinitely.19 If such a thing is possible, it could snuff out opposition and re-orient society away from what we have most reason to value.

We might also end up stagnating morally such that, for instance, the horrors of poverty or mass factory farming are never mitigated and are indeed replicated on even larger scales.

It’s hard to say exactly what could be done now to reduce the risks of these terrible outcomes. We’re generally less confident in efforts to influence trajectory changes compared to preventing extinction. If such work is feasible, it would be extremely important.

Trying to strengthen liberal democracy and promote positive values, such as by advocating on behalf of farm animals, could be valuable to this end. But many questions remain open about what kinds of interventions would be most likely to have an enduring impact on these issues over the long run.

Grappling with these issues and ensuring we have the wisdom to handle them appropriately will take a lot of work, and starting this work now could be extremely valuable.

Cobija, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Cobija, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia CommonsLongtermist research

This brings us to the third approach to longtermist work: further research.

Asking these types of questions in a systematic way is a relatively recent phenomenon. So we’re confident that we’re pretty seriously wrong about at least some parts of our understanding of these issues. There are probably several suggestions in this article that are completely wrong — the trouble is figuring out which.

So we believe much more research into whether the arguments for longtermism are sound, as well as potential avenues for having an impact on future generations, is called for. This is one reason why we include ‘global priorities research’ among the most pressing problems for people to work on.

Capacity building

The fourth category of longtermist approaches is capacity building — that is, investing in resources that may be valuable to put toward longtermist interventions down the line.

In practice, this can take a range of forms. At 80,000 Hours, we’ve played a part in building the effective altruism community, which is generally aimed at finding and understanding the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them. Longtermism is in part an offshoot of effective altruism, and having this kind of community may be an important resource for addressing the kinds of challenges longtermism raises.

There are also more straightforward ways to build resources, such as investing funds now so they can grow over time, potentially to be spent at a more pivotal time when they’re most needed.

You can also invest in capacity building by supporting institutions, such as government agencies or international bodies, that have the mission of stewarding efforts to improve the prospects of the long-term future.

Summing up the arguments

To sum up: there’s a lot on the line.

The number and size of future generations could be vast. We have reason to care about them all.

Those who come after us will have to live with the choices we make now. If they look back, we hope they’ll think we did right by them.

But the course of the future is uncertain. Humanity’s choices now can shape how events unfold. Our choices today could lead to a prosperous future for our descendants, or the end of intelligent life on Earth — or perhaps the rise of an enduring, oppressive regime.

We feel we can’t just turn away from these possibilities. Because so few of humanity’s resources have been devoted to making the future go well, those of us who have the means should figure out whether and how we can improve the chances of the best outcomes and decrease the chances of the worst.

We can’t — and don’t want to — set our descendants down a predetermined path that we choose for them now; we want to do what we can to ensure they have the chance to make a better world for themselves.

Those who come after us will have to live with the choices we make now. If they look back, we hope they’ll think we did right by them.

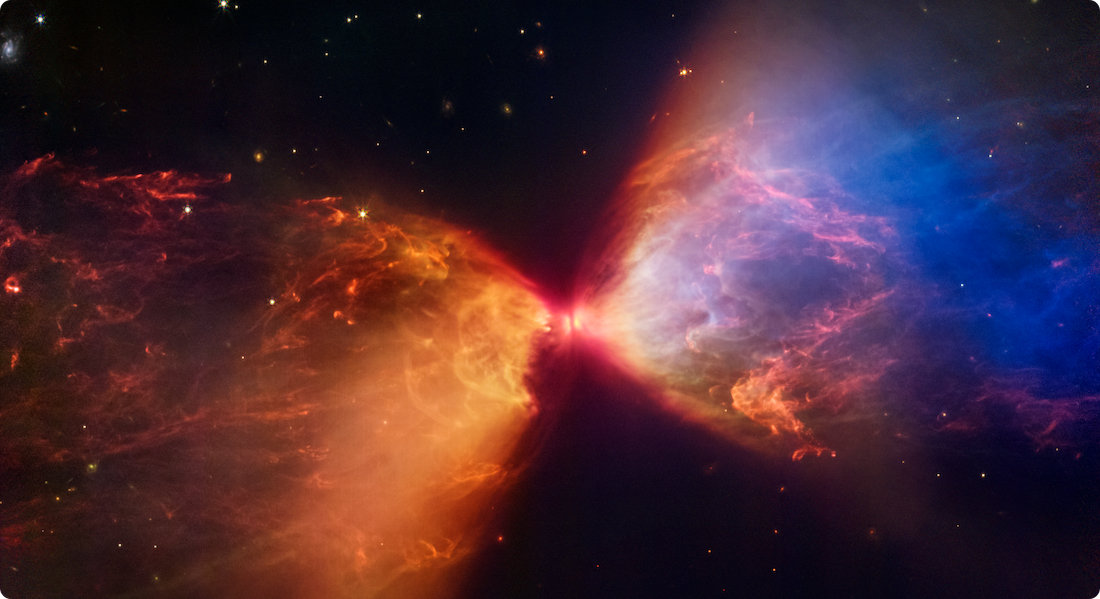

A protostar is embedded within a cloud of material feeding its growth. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

A protostar is embedded within a cloud of material feeding its growth. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScIObjections to longtermism

In what follows, we’ll discuss a series of common objections that people make to the argument for longtermism.

Some of them point to important philosophical considerations that are complex but that nonetheless seem to have solid responses. Others raise important reasons to doubt longtermism that we take seriously and that we think are worth investigating further. And some others are misunderstandings or misrepresentations of longtermism that we think should be corrected. (Note: though long, this list doesn’t cover all objections!)

Making moral decisions always involves tradeoffs. We have limited resources, so spending on one issue means we have less to spend on another. And there are many deserving causes we could devote our efforts to. If we focus on helping future generations, we will necessarily not prioritise as highly many of the urgent needs in the present.

But we don’t think this is as troubling an objection to longtermism as it may initially sound, for at least three reasons:

1. Most importantly, many longtermist priorities, especially reducing extinction risk, are also incredibly important for people alive today. For example, we believe preventing an AI-related catastrophe or a cataclysmic pandemic are two of the top priorities, in large part because of their implications for future generations. But these risks could materialise in the coming decades, so if our efforts succeed most people alive today would benefit. Some argue that preventing global catastrophes could actually be the single most effective way to save the lives of people in the present.

2. If we all took moral impartiality more seriously, there would be a lot more resources going to help the worst-off today — not just the far future. Impartiality is the idea that we should care about the interests of individuals equally, regardless of their nationality, gender, race, or other characteristics that are morally irrelevant. This impartiality is part of what motivates longtermism — we think the interests of future individuals are often unjustifiably undervalued.

We think if impartiality were taken more seriously in general, we’d live in a much better world that would commit many more resources than it currently does toward alleviating all kinds of suffering, including for the present generation. For example, we’d love to see more resources go toward fighting diseases, improving mental health, reducing poverty, and protecting the interests of animals.

3. Advocating for any moral priority means time and resources are not going to another cause that may also be quite worthy of attention. Advocates for farmed animals’ or prisoners’ rights are in effect deprioritising the interests of alternative potential beneficiaries, such as the global poor. So this is not just an objection to longtermism — it’s an objection to any kind of prioritisation.

Ultimately, this objection hinges on the question of whether future generations are really worth caring about — which is what the rest of this article is about.

Some people, especially those trained in economics, claim that we shouldn’t treat individual lives in the future equally to lives today. Instead, they argue, we should systematically discount the value of future lives and generations by a fixed percentage.

(We’re not talking here about discounting the future due to uncertainty, which we cover below.)

When economists compare benefits in the future to benefits in the present, they typically reduce the value of the future benefits by some amount called the “discount factor.” A typical rate might be 1% per year, which means that benefits in 100 years are only worth 36% as much as benefits today, and benefits in 1,000 years are worth almost nothing.

This may seem like an appealing way to preserve the basic intuition we began with — that we have strong reasons to care about the wellbeing of future generations — while avoiding the more counterintuitive longtermist claims that arise from considering the potentially astronomical amounts of value that our universe might one day hold. On this view, we would care about future generations, but not as much as the present generation, and mostly only the generations that will come soon after us.

We agree there are good reasons to discount economic benefits. One reason is that if you receive money now, you can invest it, and earn a return each year. This means it’s better to receive money now rather than later. People in the future might also be wealthier, which means that money is less valuable to them.

However, these reasons don’t seem to apply to welfare — people having good lives. You can’t directly ‘invest’ welfare today and get more welfare later, like you can with money. The same seems true for other intrinsic values, such as justice. And longtermism is about reasons to care about the interests of future generations, rather than wealth.

As far as we know, most philosophers who have worked on the issue don’t think we should discount the intrinsic value of future lives — even while they strongly disagree about other questions in population ethics. It’s a simple principle that is easy to accept: one person’s happiness is worth just the same amount no matter when it occurs.

Indeed, if you suppose we can discount lives in the far future, we can easily end up with conclusions that sound absurd. For instance, a 3% discount rate would imply that the suffering of one person today is morally equal to the suffering of 16 trillion people in 1,000 years. This seems like a truly horrific conclusion to accept.

And any discount rate will mean that, if we found some reliable way to save 1 million lives from intense suffering in either 1,000 years or 10,000 years, it would be astronomically more important to choose the sooner option. This, too, seems very hard to accept.20

If we reject the discounting of the value of future lives, then the many potential generations that could come after us are still worthy of moral concern. And this doesn’t stand in tension with the economic practice of discounting monetary benefits.

If you’d like to see a more technical discussion of these issues, see Discounting for Climate Change by Hilary Graves. There is a more accessible discussion at 1h00m50s in our podcast with Toby Ord and in Chapter 4 of Stubborn Attachments by Tyler Cowen.

There are some practical, rather than intrinsic, reasons to discount the value of the future. In particular, our uncertainty about how the future will unfold makes it much harder to influence than the present, and even more near-term actions can be exceedingly difficult to forecast.

And because of the possibility of extinction, we can’t even be confident that the future lives we think are so potentially valuable will come into existence. As we’ve argued, that gives us reason to reduce extinction risks when it’s feasible — but it also gives us reason to be less confident these lives will exist and thus to weight them somewhat less in our deliberations.

In the same way, a doctor performing triage may choose to prioritise caring for a patient who had a good chance of surviving their injuries over one who has much less clear likelihood of survival regardless of the medical care they receive.

This uncertainty — along with the extreme level of difficulty in trying to predict the long-term impacts of our actions — certainly makes it much harder to help future generations, all else equal. And in effect, this point lowers the value of working to benefit future generations.

So even if we can affect how things unfold for future generations, we’re generally going to be very far from certain that we are actually making things better. And arguably, the further away in time the outcomes of our actions are, the less sure we can be that they will come about. Trying to improve the future will never be straightforward.

Still, even given the difficulty and uncertainty, we think the potential value at stake for the future means that many uncertain projects are still well worth the effort.

You might disagree with this conclusion if you believe that human extinction is so likely and practically unavoidable in the future that the chance that our descendants will still be around rapidly declines as we look a few centuries down the line. We don’t think it’s that likely — though we are worried about it.

Journalist Kelsey Piper critiqued MacAskill’s argument for longtermist interventions focused on positive trajectory changes (as opposed to extinction risks) in Asterisk, writing:

What share of people who tried to affect the long-term future succeeded, and what share failed? How many others successfully founded institutions that outlived them — but which developed values that had little to do with their own?

…

Most well-intentioned, well-conceived plans falter on contact with reality. Every simple problem splinters, on closer examination, into dozens of sub-problems with their own complexities. It has taken exhaustive trial and error and volumes of empirical research to establish even the most basic things about what works and what doesn’t to improve peoples’ lives.

Piper does still endorse working on extinction reduction, which she thinks is a more tractable course of action. Her doubts about the possibility of reliably anticipating our impact on the trajectory of the future, outside of extinction scenarios, are worth taking very seriously.

You might have a worry about longtermism that goes deeper than just uncertainty. We act under conditions of uncertainty all the time, and we find ways to manage it.

There is a deeper problem known as cluelessness. While uncertainty is about having incomplete knowledge, cluelessness refers to the state of having essentially no basis of knowledge at all.

Some people believe we’re essentially clueless about the long-term effects of our actions. This is because virtually every action we take may have extremely far-reaching unpredictable consequences. In time travel stories, this is sometimes referred to as the “butterfly effect” — because something as small as a butterfly flapping its wings might influence air currents just enough to cause a monsoon on the other side of the world (at least for illustrative purposes).

If you think your decision of whether to go to the grocery store on Thursday or Friday might determine whether the next Gandhi or Stalin is born, you might conclude that actively trying to make the future go well is a hopeless task.

Like some other important issues discussed here, cluelessness remains an active area of philosophical debate, so we don’t think there’s necessarily a decisive answer to these worries. But there is a plausible argument, advanced philosopher and advisor to 80,000 Hours Hilary Greaves that longtermism is, in fact, the best response to the issue of cluelessness.

This is because cluelessness hangs over the impact of all of our actions. Work trying to improve the lives of current generations, such as direct cash transfers, may predictably benefit a family in the foreseeable future. But the long-term consequences of the transfer are a complete mystery.

Successful longtermist interventions, though, may not have this quality — particularly interventions to prevent human extinction. If we, say, divert an asteroid that would otherwise have caused the extinction of humanity, we are not clueless about the long-term consequences. Humanity will at least have the chance to continue existing into the far future, which it wouldn’t have otherwise had.

There’s still uncertainty, of course, in preventing extinction. The long-term consequences of such an action aren’t fully knowable. But we’re not clueless about them either.

If it’s correct that the problem of cluelessness bites harder for some near-term interventions than longtermist ones, and perhaps least of all for preventing extinction, then this apparent objection doesn’t actually count against longtermism.

For an alternative perspective, though, check out The 80,000 Hours Podcast interview with Alexander Berger.

Because of the nature of human reproduction, the identity of who gets to be born is highly contingent. Any individual is the result of the combination of one sperm and one egg, and a different combination of sperm and egg would’ve created a different person. Delaying the act of conception at all — for example, by getting stuck at a red light on your way home — can easily result in a different sperm fertilising the egg, which means another person with a different combination of genes will be born.

This means — somewhat surprisingly — that pretty much all our actions have the potential to impact the future by changing which individuals get born in the future.

If you care about affecting the future in a positive way, this creates a perplexing problem. Many actions undertaken to improve the future, such as trying to reduce the harmful effects of climate change or developing a new technology to improve people’s lives, may deliver the vast majority of their benefits to people who wouldn’t have existed had the course of action never been taken.

So while it seems obviously good to improve the world in this way, it may be impossible to ever point to specific people in the future and say they were made better off by these actions. You can make the future better overall, but you may not make it better for anyone in particular.

Of course, the reverse is true: you may take some action that makes the future much worse, but all the people who experience the consequences of your actions may never have existed had you chosen a different course of action.

This is known as the ‘non-identity problem.’ Even when you can make the far future better with a particular course of action, you will almost certainly never make any particular individuals in the far future better off than they otherwise would be.

Should this problem cause us to abandon longtermism? We don’t think so.

While the issue is perplexing, accepting it as a refutation of longtermism would prove too much. It would, for example, undermine much of the very plausible case that policymakers should in the past have taken significant steps to limit the effects of climate change (since those policy changes can be expected to, in the long run, lead to different people being born).

Or consider a hypothetical case of a society that is deciding what to do with its nuclear waste. Suppose there are two ways of storing it: one way is cheap, but it means that in 200 years time, the waste will overheat and expose 10,000,000 people to sickening radiation that dramatically shortens their lives. The other storage method guarantees it will never hurt anyone, but it is significantly more expensive, and it means currently living people will have to pay marginally higher taxes.

Assuming this tax policy alters behaviour just enough to start changing the identities of the children being born, it’s entirely plausible that, in 200 years time, no one would exist who would’ve existed if the cheap, dangerous policy had been implemented. This means that none of the 10,000,000 people who have their lives cut short can say they would have been better off had their ancestors chosen the safer storage method.21

Still, it seems intuitively and philosophically unacceptable to believe that a society wouldn’t have very strong reasons to adopt the safe policy over the cheap, dangerous policy. If you agree with this conclusion, then you agree that the non-identity problem does not mean we should abandon longtermism. (You may still object to longtermism on other grounds!)

Nevertheless, this puzzle raises pressing philosophical questions that continue to generate debate, and we think better understanding these issues is an important project.

We said that we thought it would be very bad if humanity was extinguished, in part because future individuals who might have otherwise been able to live full and flourishing lives wouldn’t ever get the chance.

But this raises some issues related to the ‘non-identity problem.’ Should we actually care whether future generations come into existence, rather than not?

Some people argue that perhaps we don’t actually have moral reasons to do things that affect whether individuals exist — in which case ensuring that future generations get to exist, or increasing the chance that humanity’s future is long and expansive or would be morally neutral in itself.

This issue is very tricky from a philosophical perspective; indeed, a minor subfield of moral philosophy called population ethics sets out to answer this and related questions.

So we can’t expect to fully address the question here. But we can give a sense of why we think working to ensure humanity survives and that the future is filled with flourishing lives is a high moral priority.

Consider first a scenario in which you, while travelling the galaxy in a spaceship, come across a planet filled with an intelligent species leading happy, moral, fulfilled lives. They haven’t achieved spaceflight, and may never do so, but they appear likely to have a long future ahead of them on their planet.

Would it not seem like a major tragedy if, say, an asteroid were on course to destroy their civilization? Of course, any plausible moral view would advise saving the species for their own sakes. But it also seems like it’s an unalloyed good that, if you divert the asteroid, this flourishing species will be able to continue on for many future generations, flourishing in their corner of the universe.

If we have that view about that hypothetical alien world, we should probably have the same view of our own planet. Humans, of course, aren’t necessarily that happy, moral, and fulfilled for their lives. But the vast majority of us want to keep living — and it seems at least possible that our descendants could have lives many times more flourishing than we have. They might even ensure that all other sentient beings have joyous lives well-worth living. This seems to give us strong reasons to make this potential a reality.

For a different kind of argument along these lines, you can read Joe Carlsmith’s “Against neutrality about creating happy lives.”

Some people advocate a ‘person-affecting’ view of ethics. This view is sometimes summed up with the quip: “ethics is about helping make people happy, not making happy people.”

In practice, this means we only have moral obligations to help those who are already alive22 — not to enable more people to exist with good lives. For people who hold such views, it may be permissible to create a happy person, but doing so is morally neutral.

This view has some plausibility, and we don’t think it can be totally ignored. However, philosophers have uncovered a number of problems with it.

Suppose you have the choice to bring into existence one person with an amazing life, or another person whose life is barely worth living, but still more good than bad. Clearly, it seems better to bring about the amazing life.

But if creating a happy life is neither good nor bad, then we have to conclude that both options are neither good nor bad. This implies the options are equal, and you have no reason to do one or the other, which seems bizarre.

And if we accepted a person-affecting view, it might be hard to make sense of many of our common moral beliefs around issues like climate change. For example, it would imply that policymakers in the 20th century might have had little reason to mitigate the impact of CO2 emissions on the atmosphere if the negative effects would only affect people who would be born several decades in the future. (This issue is discussed more above.)

This is a complex debate, and rejecting the person-affecting view also has counterintuitive conclusions. In particular, Parfit showed that if you agree that it’s good to create people whose lives are more good than bad, there is a strong argument for the conclusion that we could have a better world filled with a huge number of people whose lives are just barely worth living. He called this the “repugnant conclusion”.

Both sides make important points in this debate. You can see a summary of the arguments in this public lecture by Hilary Greaves (based on this paper). It’s also discussed in our podcast with Toby Ord.

We’re uncertain about what the right position is, but we’re inclined to reject person-affecting views. Since many people hold something like the person-affecting view, though, we think it deserves some weight, and that means we should act as if we have somewhat greater obligations to help someone who’s already alive compared to someone who doesn’t exist yet. (This is an application of moral uncertainty).

One note however: even people who otherwise embrace a person-affecting view often think that is morally bad to do something that brings someone into existence who has a life full of suffering and who wishes they’d never been born. If that’s right, you should still think that we have strong moral reasons to care about the far future, because there’s the possibility it could be horrendously bad as well as very good for a large number of individuals. On any plausible view, there’s a forceful case to be made for working to avert astronomical amounts of suffering. So even someone who believes strongly in a person-affecting view of ethics might have reason to embrace a form of longtermism that prioritises averting large-scale suffering in the future.

Trying to weigh this up, we think society should have far greater concern for the future than it does now, and that as with climate change, it often makes sense to prioritise making things go well for future individuals. In the case of climate change, for example, it was likely the case that society should have long ago taken on the non-trivial costs of financing efforts to develop highly reliable clean energy and navigating away from a carbon-intensive economy.

Because of moral uncertainty, though, we care more about the present generation than we would if we naively weighed up the numbers.

Isn't it arrogant to think we'll know what will happen in hundreds, thousands, or millions of years?

Yes, it would be arrogant. But longtermism doesn’t require us to know the future.

Instead, the practical implication of longtermism is that we take steps that are likely to be good over the wide range of possible futures. We think it’s likely better for the future if, as we said above, we avoid extinction, we manage our resources carefully, we foster institutions that promote cooperation rather than violent conflict, and we responsibly develop powerful technology. None of these strategies requires us knowing what the future will look like.

We talk more about the importance of all this uncertainty in the sections above.

This isn’t exactly an objection, but one response to longtermism asserts not that the view is badly off track but that it’s superfluous.

This may seem plausible if longtermism primarily inspires us to prioritise reducing extinction risks. As discussed above, doing so could benefit existing people — so why even bother talking about the benefits to future generations?

One reply is: we agree that you don’t need to embrace longtermism to support these causes! And we’re happy if people do good work whether or not they agree with us on the philosophy.

But we still think the argument for longtermism is true, and we think it’s worth talking about.

Firstly, when we actually try to compare the importance of work in certain cause areas — such as global health or mitigating the risk of extinction from nuclear war — whether and how much we weigh the interests of future generations may play a decisive role in our conclusions about prioritisation.

Moreover, some longtermist priorities, such as ensuring that we avoid the lock-in of bad values or developing a promising framework for space governance, may be entirely ignored if we don’t consider the interests of future generations.

Finally, if it’s right that future generations deserve much more moral concern than they currently get, it just seems good for people to know that. Maybe issues will come up in the future that aren’t extinction threats but which could still predictably affect the long-run future – we’d want people to take those issues seriously.

In short, no. Total utilitarianism is the view that we are obligated to maximise the total amount of positive experiences over negative experiences, typically by weighting for intensity and duration.

This is one specific moral view, and many of its proponents and sympathisers advocate for longtermism. But you can easily reject utilitarianism of any kind and still embrace longtermism.

For example, you might believe in ‘side constraints’ — moral rules about what kinds of actions are impermissible, regardless of the consequences. So you might believe that you have strong reasons to promote the wellbeing of individuals in the far future, so long as doing so doesn’t require violating anyone’s moral rights. This would be one kind of non-utilitarian longtermist view.

You might also be a pluralist about value, in contrast to utilitarians who think a singular notion of wellbeing is the sole true value. A non-utilitarian might intrinsically value, for instance, art, beauty, achievement, good character, knowledge, and personal relationships, quite separately from their impact on wellbeing.

(See our definition of social impact for how we incorporate these moral values into our worldview.)

So you might be a longtermist precisely because you believe the future is likely to contain vast amounts of all the many things you value, so it’s really important that we protect this potential.

You could also think we have an obligation to improve the world for future generations because we owe it to humanity to “pass the torch”, rather than squander everything people have done to build up civilisation. This would be another way of understanding moral longtermism that doesn’t rely on total utilitarianism.23

Finally, you can reject the “total” part of utilitarianism and still believe longtermism. That is, you might believe it’s important to make sure the future goes well in a generally utilitarian sense without thinking that means we’ll need to keep increasing the population size in order to maximise total wellbeing. You can read more about different kinds of views in population ethics here.

As we discussed above, people who don’t think it’s morally good to bring a flourishing population into existence usually think it’s still important to prevent future suffering — in which case you might support a longtermism focused on guarding against the worst outcomes for future generations.

No.

We believe, for instance, that you shouldn’t have a harmful career just because you think you can do more good than bad with the money you’ll earn. There are practical, epistemic, and moral reasons that justify this stance.

And as a general matter, we think it’s highly unlikely to be the case that working in a harmful career will be the path that has the best consequences overall.

Some critics of longtermism say the view can be used to justify all kinds of egregious acts in the name of a glorious future. We do not believe this, in part because there are plenty of plausible intrinsic reasons to object to egregious acts on their own, even if you think they’ll have good consequences. As we explained in our article on the definition of ‘social impact’:

We don’t think social impact is all that matters. Rather, we think people should aim to have a greater social impact within the constraints of not sacrificing other important values – in particular, while building good character, respecting rights and attending to other important personal values. We don’t endorse doing something that seems very wrong from a commonsense perspective in order to have a greater social impact.

Perhaps even more importantly, it’s bizarrely pessimistic to believe that the best way to make the future go well is to do horrible things now. This is very likely false, and there’s little reason anyone should be tempted by this view.

Some of the claims in this article may sound like science fiction. We’re aware this can be off-putting to some readers, but we think it’s important to be upfront about our thinking.

And the fact that a claim sounds like science fiction is not, on its own, a good reason to dismiss it. Many speculative claims about the future have sounded like science fiction until technological developments made them a reality.

From Eunice Newton Foote’s perspective in the 19th century, the idea that the global climate would actually be transformed based on a principle she discovered in a glass cylinder may have sounded like science fiction. But climate change is now our reality.

Similarly, the idea of the “atomic bomb” had literally been science fiction before Leo Szilard discovered the possibility of the nuclear chain reaction in 1933. Szilard first read about such weapons in H.G. Wells’ The World Set Free. As W. Warren Wager explained in The Virginia Quarterly:

Unlike most scientists then doing research into radioactivity, Szilard perceived at once that a nuclear chain reaction could produce weapons as well as engines. After further research, he took his ideas for a chain reaction to the British War Office and later the Admiralty, assigning his patent to the Admiralty to keep the news from reaching the notice of the scientific community at large. “Knowing what this [a chain reaction] would mean,” he wrote, “—and I knew it because I had read H.G. Wells—I did not want this patent to become public.”

This doesn’t mean we should accept any idea without criticism. And indeed, you can reject many of the more ‘sci-fi’ claims of some people who are concerned with future generations — such as the possibility of space settlement or the risks from artificial intelligence — and still find longtermism compelling.

One worry about longtermism some people have is that it seems to rely on having a very small chance of achieving a very good outcome.

Some people think this sounds suspiciously like Pascal’s wager, a highly contentious argument for believing in God — or a variant of this idea, “Pascal’s mugging.” The concern is that this type of argument may be used to imply an apparent obligation to do absurd or objectionable things. It’s based on a thought experiment, as we described in a different article:

A random mugger stops you on the street and says, “Give me your wallet or I’ll cast a spell of torture on you and everyone who has ever lived.” You can’t rule out with 100% probability that he won’t — after all, nothing’s 100% for sure. And torturing everyone who’s ever lived is so bad that surely even avoiding a tiny, tiny probability of that is worth the $40 in your wallet? But intuitively, it seems like you shouldn’t give your wallet to someone just because they threaten you with something completely implausible.

This deceptively simple problem raises tricky issues in expected value theory, and it’s not clear how they should be resolved — but it’s typically assumed that we should reject arguments that rely on this type of reasoning.

The argument for longtermism given above may look like a form of this argument because it relies in part on the premise that the number of individuals in the future could be so large. Since it’s a relatively novel, unconventional argument, it may sound suspiciously like the mugger’s (presumably hollow) threat in the thought experiment.

But there are some key differences. To start, the risks to the long-term future may be far from negligible. Toby Ord estimated the chance of an existential catastrophe that effectively curtails the potential of future generations in the next century at 1 in 6.24

Now, it may be true that any individual’s chance of meaningfully reducing these kinds of threats is much, much smaller. But we accept small chances of doing good all the time — that’s why you might wear a seatbelt in a car, even though in any given drive your chances of being in a serious accident are miniscule. Many people buy life insurance to guarantee that their family members will have financial support in the unlikely scenario that they die young.

And while an individual is unlikely to be solely responsible for driving down the risk of human extinction by any significant amount (in the same way no one individual could stop climate change), it does seem plausible that a large group of people working diligently and carefully might be able to do it. And if the large group of people can achieve this laudable end, then taking part in this collective action isn’t comparable to Pascal’s mugging.

But if we did conclude the chance to reduce the risks humanity faces is truly negligible, then we would want to look much more seriously into other priorities, especially since there are so many other pressing problems. As long as it’s true, though, that there are genuine opportunities to have a significant impact on improving the prospects for the future, then longtermism does not rely on suspect and extreme expected value reasoning.

This is a lot to think about. So what are our bottom lines on how we think we’re most likely to be wrong about longtermism?

Here are a few possibilities we think are worth taking seriously, even though they don’t totally undermine the case from our perspective:

- Morality may require a strong preference for the present: There might be strong moral reasons to give preference to existing people and individuals over future generations. This might be because something like a person-affecting view is true (described above) or maybe even because we should systematically discount the value of future beings.

- We don’t think the arguments for such a strong preference are very compelling, but given the high levels of uncertainty in our moral beliefs, we can’t confidently rule it out.

- Reliably affecting the future may be infeasible. It’s possible that further research will ultimately conclude that the opportunities for impacting the far future are essentially non-existent or extremely limited. It’s hard to believe we could ever entirely close the question — researchers who come to this conclusion in the future could themselves be mistaken — but it might dramatically reduce our confidence that pursuing a longtermist agenda is worthwhile and thus leave the project as a pretty marginal endeavour.

Reducing extinction risk may be intractable beyond a certain point. It’s possible that there’s a base level of extinction risk that humans will have to accept at some point and that we can’t reduce any further. And if, for instance, there were an irreducible risk of an extinction catastrophe at 10 percent every century, then the future, in expectation, would be much less significant than we think. This would dramatically reduce the pull of longtermism.

A crucial consideration could change our assessment in ways we can’t predict. This falls into the general category of ‘unknown unknowns,’ which are always important to be on the watch for.

You could also read the following essays criticising longtermism that we have found interesting:

- A review of The Precipice written by Theron Pummer

- A blog post called “Against Longtermism” by Eric Schwitzgebel

- A post on the Effective Altruism Forum by Denise Melchin called “Why I am probably not a longtermist“

If I don’t agree with 80,000 Hours about longtermism, can I still benefit from your advice?

Yes!

We want to be candid about what we believe and what our priorities are, but we don’t think everyone needs to agree with us.

And we have lots of advice and tools that are broadly useful for people thinking about their careers, regardless of what they think about longtermism.

There are also many places where longtermist projects converge with other approaches to thinking about having a positive impact with your career. For example, working to prevent pandemics seems robustly good whether you prioritise near- or long-term benefits.

Though we focus as an organisation on issues that may affect all future generations, we would generally be really happy to also see more people working for the benefit of the global poor and farmed animals, two tractable causes that we think are unduly neglected in the near term. We also discuss these issues on our podcast and list jobs for them on our job board.

Credit: Yen Chao CC2.0

Credit: Yen Chao CC2.0What are the best ways to help future generations right now?

While answering this question satisfactorily would require a sweeping research agenda in itself, we do have some general thoughts about what longtermism means for our practical decision making. And we’d be excited to see more attention paid to this question.

Some people may be motivated by these arguments to find opportunities to donate to longermist projects or cause areas. We believe Open Philanthropy — which is a major funder of 80,000 Hours — does important work in this area.

But our primary aim is to help people have impactful careers. Informed by longtermism, we have created a list of what we believe are the most pressing problems to work on in the world. These problems are important, neglected, and tractable.

As of this writing, the top eight problem areas are:

- Risks from artificial intelligence

- Catastrophic pandemics

- Building effective altruism

- Global priorities research

- Nuclear war

- Improving decision making (especially in important institutions)

- Climate change

- Great power conflict

We’ve already given few examples of concrete ways to tackle these issues above.

The above list is provisional, and it is likely to change as we learn more. We also list many other pressing problems that we believe are highly important from a longtermist point of view, as well as a few that would be high priorities if we rejected longtermism.

We hope more people will challenge our ideas and help us think more clearly about them. As we have argued, the stakes are incredibly high.

We have a related list of high-impact careers that we believe are appealing options for people who want to work to address these and related problems and to help the long-term future go well.

But we don’t have all the answers. Research in this area could reveal crucial considerations that might overturn longtermism or cast it in a very different light. There are likely pressing cause areas we haven’t thought of yet.

We hope more people will challenge our ideas and help us think more clearly about them. As we have argued, the stakes are incredibly high. So it’s paramount that, as much as is feasible, we get this right.

Want to focus your career on the long-run future?

If you want to work on ensuring the future goes well, such as controlling nuclear weapons or shaping the development of artificial intelligence or biotechnology, you can speak to our team one-on-one.

We’ve helped hundreds of people choose an area to focus, make connections, and then find jobs and funding in these areas. If you’re already in one of these areas, we can help you increase your impact within it.

Learn more

- Toby Ord discussed these arguments in his book, The Precipice, and he discussed the ideas with us on our podcast.

- Will MacAskill also made the argument in his book, What We Owe the Future, and we interviewed him about it on our podcast.

- Benjamin Todd and Arden Koehler discussed varieties of longtermism in this podcast.

- Hilary Greaves presented the case for longtermism at Oxford University.

- In this podcast, Holden Karnofsky talked about the case that we’re living in the most important century.

- Article: The case for reducing existential risks

- Podcast: Carl Shulman on the common-sense case for existential risk work and its practical implications

- Podcast: Anders Sandberg on war in space, whether civilisations age, and the best things possible in our universe

Read next

This article is part of our advanced series. See the full series, or keep reading:

Notes and references

- This discovery was discussed in an article by Clive Thompson in JSTOR Daily.↩

- She added that “if as some suppose, at one period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature from its own action as well as from increased weight must have necessarily resulted.”↩

- “While some models showed too much warming and a few showed too little, most models examined showed warming consistent with observations, particularly when mismatches between projected and observationally informed estimates of forcing were taken into account. We find no evidence that the climate models evaluated in this paper have systematically overestimated or underestimated warming over their projection period. The projection skill of the 1970s models is particularly impressive given the limited observational evidence of warming at the time, as the world was thought to have been cooling for the past few decades.” ‘Evaluating the Performance of Past Climate Model Projections.’↩

- In his book What We Owe the Future, Will MacAskill (a co-founder and trustee of 80,000 Hours) is even more succinct: “Future people count. There could be a lot of them. We can make their lives go better.” (pg. 9)↩

- “Setting aside climate change, all spending on biosecurity, natural risks and risks from AI and nuclear war is still substantially less than we spend on ice cream. And I’m confident that the spending actually focused on existential risk is less than one-tenth of this.” The Precipice (pg. 313)↩

- Derek Parfit in Reasons and Persons on pages 356-357↩

- John Adams, the second president of the United States who laid some of the intellectual foundations for the US Constitution, pointed to the importance of enduring governmental structures in his own writing: “The institutions now made in America will not wholly wear out for thousands of years. It is of the last importance, then, that they should begin right. If they set out wrong, they will never be able to return, unless it be by accident, to the right path.” Quoted in MacAskill’s What We Owe the Future.↩

- See The Biology of Rarity edited by W.E. Kunin, K.J. Gaston↩

- “The average lifespan of a species varies according to taxonomic group. It is as long as tens of millions of years for ants and trees, and as short as half a million years for mammals. The average span across all groups combined appears to be (very roughly) a million years.” — Professor Edward O. Wilson↩

- Some might believe it’s just entirely implausible to believe humans could be around for another 500 million years. But consider, as Toby Ord precipice pointed out in The Precipice, that the fossil record indicates that horseshoe crabs have existed essentially unchanged on the planet for at least around 445 million. Of course, horseshoe crabs undoubtedly have features that make them particularly resilient as a species. But humans, too, have undeniably unique characteristics, and it’s arguable that these features could confer comparable or even superior survival advantages.↩

- See Chapter 8 of Toby Ord’s The Precipice for a detailed discussion of the prospects for space settlement.↩

- In a previous version of this article, Ben Todd explained how simple expected value calculations can give a sense of how significantly the future can weigh in our deliberations:

If there’s a 5% chance that civilisation lasts for 10 million years, then in expectation, there are over 5,000 future generations. If thousands of people making a concerted effort could, with a 55% probability, reduce the risk of premature extinction by 1 percentage point, then these efforts would in expectation save 28 future generations. If each generation contains 10 billion people, that would be 280 billion additional individuals who get to live flourishing lives. If there’s a chance civilisation lasts longer than 10 million years, or that there are more than 10 billion people in each future generation, then the argument is strengthened even further.

This is just a toy model, and it doesn’t actually capture all the ways we should think about value. But it shows why we should care about future generations, even if we’re not sure they’ll come into existence.↩

- Saulius Šimčikas of Rethink Priorities in 2020 researched the numbers of vertebrate animals in captivity. The report found that there were between 9.5 and 16.2 billion chickens, bred for meat in captivity, on any given day. There are also 1.5 billion cattle, 978 million pigs, and 103 billion farmed fish, among many other types of farmed animals.↩

- Altogether, this means there are many, many lives at stake in the way the future unfolds. A conservative estimate of the upper bound (assuming just Earth-bound humans) is 1016. But estimates using different approaches put the figure as high as 1035, or even — very speculatively — 1058. These figures and other estimates are discussed in “How many lives does the future hold?” by Toby Newbury.↩

- Note that we think the near-term risk from natural threats tends to be much lower than human-made threats.

Toby Ord explained on The 80,000 Hours Podcast why he believes extinction risk from natural causes is relatively low: “[We’ve] been around for about 2,000 centuries: homo sapiens. Longer, if you think about the homo genus. And, suppose the existential risk per century were 1%. Well, what’s the chance that you would get through 2,000 centuries of 1% risk? It turns out to be really low because of how exponentials work, and you have almost no chance of surviving that. So this gives us a kind of argument that the risk from natural causes, assuming it hasn’t been increasing over time, that this risk must be quite low.”↩

- We’re also very concerned about mitigating climate change, though at this point, we believe it’s much less likely to cause human extinction on its own.↩

- What about non-human animals? One might wonder whether this emphasis on the extinction of our own species is overly human-centric.

There might be some scenarios in which humanity goes extinct, but many other animal species continue to live for the rest of Earth’s habitable period. Does that mean that avoiding human extinction is much less important than we thought, since we believe non-human lives have value?

Probably not, for at least three reasons:

1. Without the ability to migrate to the stars, Earth-derived life may fall well below its apparent potential. It’s possible another species on Earth would evolve human-level intelligence and capacities, but we shouldn’t bet on it. As far as we can tell, it took around 3.5 billion years since life first emerged on Earth for human intelligence to reach its current state. It’s possible that animals with human-like intelligence would emerge on our planet again more quickly if we went extinct, but we shouldn’t rely on the idea that the planet has enough time left to pull off the same trick twice.

2. Wild animals may face extreme amounts of suffering, and it’s not clear how often their lives are worth living. If it’s true that many wild animal lives are full of pain and suffering, we should hope humans are around in the future – if nothing else to consider mitigating those harms. It could be best from the perspective of wild animals if humans did not go extinct, so that humans could improve the lives of wild animals.

3. We still have a lot of uncertainty about what a valuable future should look like, and it’s important to preserve the one species we know of that is at least somewhat capable of seriously deliberating about what matters and acting on its conclusions. We may yet fail to secure a valuable future, but it’s much more likely that we’ll get there by trying than if we leave it up to random chance or natural processes. If the course of the future were decided by random or natural processes, we might expect it to fall short of almost all its potential.↩

- Note that while reducing extinction risks and trajectory changes are split up in this explanation, they may, in practice, imply similar courses of action. Work to prevent, say, a catastrophic pandemic that kills all humans could likely also be effective at preventing a pandemic that allows some humans to survive but causes society to irreversibly collapse.↩

- It seems plausible that reducing the risk of this outcome could be the most important cause to work on. However, it’s not clear to us what steps are available at this time to meaningfully do so.↩

- It’s possible we’d prefer to act to prevent the suffering in 1,000 years rather than 10,000 years, because we feel less confident we can predict what will happen in 10,000 years. It seems plausible, for instance, that the greater length of time would make it more likely that someone else will find a way to prevent the harm. But if we assume that our uncertainty about the likelihood of the suffering in each case is the same, there seems to be no reason at all to prefer to prevent the sooner suffering rather than the later.↩

- If the radiation sickness is so bad that it makes their lives worse than nonexistence, they might be able to object to choosing any policy that allowed them to be born. But we can ignore this possibility for the point being made here.↩

- Some person-affecting views do assert that we have obligations to future individuals if a given individual or set of individuals will exist regardless of our actions. (Because of the extreme contingency in much of animal reproduction, the identity of future individuals is often not fixed.) For more information on this, see the entry on the non-identity problem in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.↩

- For an example of this view, read Leopold Aschenbrenner’s blog post on “Burkean Longtermism.”↩

- Some researchers estimate that the chance of extinction is significantly lower; others believe it’s much higher. But it seems hard to be confident the risks are extremely low. Assessing the level of risk we face is plausibly a top longtermist priority.↩