Marc Lipsitch on whether we’re winning or losing against COVID-19

By Robert Wiblin and Keiran Harris · Published May 18th, 2020

Marc Lipsitch on whether we’re winning or losing against COVID-19

By Robert Wiblin and Keiran Harris · Published May 18th, 2020

On this page:

- Introduction

- 1 Highlights

- 2 Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

- 3 Transcript

- 3.1 Rob's intro [00:00:00]

- 3.2 The interview begins [00:01:45]

- 3.3 Things Rob wishes he knew about COVID-19 [00:05:23]

- 3.4 Cross-country comparisons [00:10:53]

- 3.5 Any government activities we should stop? [00:21:24]

- 3.6 Lessons from COVID-19 [00:33:31]

- 3.7 Global catastrophic biological risks [00:37:58]

- 3.8 Human challenge trials [00:43:12]

- 3.9 Disease surveillance [00:50:07]

- 3.10 Who should we trust? [00:58:12]

- 3.11 Epidemiology as a field [01:13:05]

- 3.12 Careers [01:31:28]

- 3.13 Rob's outro [01:36:40]

- 4 Learn more

- 5 Related episodes

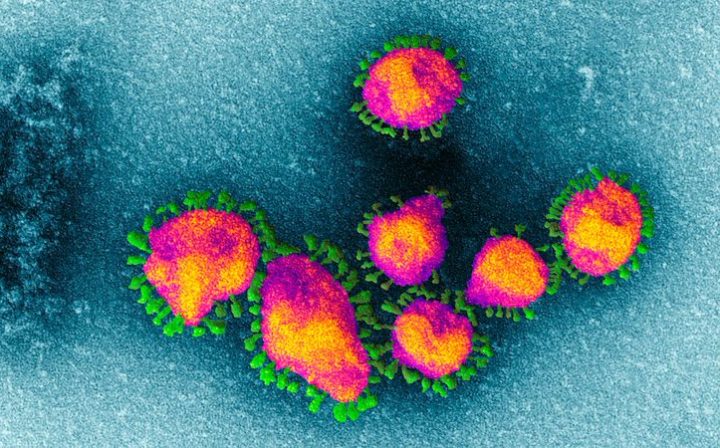

Public health poster drawn by Le Duc Hiep. Learn more about coronavirus artists in Vietnam.

…I think it remains to be seen whether we in the United States can do better than just letting everybody get it gradually … If it’s about 5 or 10% of the population now, I can’t envision a scenario where we have a vaccine or a really good treatment before it’s about twice that. … Clearly we need a lot of creative thinking about alternative ways to make life go on.

Marc Lipsitch

In March Professor Marc Lipsitch — director of Harvard’s Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics — abruptly found himself a global celebrity, his social media following growing 40-fold and journalists knocking down his door, as everyone turned to him for information they could trust.

Here he lays out where the fight against COVID-19 stands today, why he’s open to deliberately giving people COVID-19 to speed up vaccine development, and how we could do better next time.

As Marc tells us, island nations like Taiwan and New Zealand are successfully suppressing SARS-COV-2. But everyone else is struggling.

Even Singapore, with plenty of warning and one of the best test and trace systems in the world, lost control of the virus in mid-April after successfully holding back the tide for 2 months.

This doesn’t bode well for how the US or Europe will cope as they ease their lockdowns. It also suggests it would have been exceedingly hard for China to stop the virus before it spread overseas.

But sadly, there’s no easy way out.

The original estimates of COVID-19’s infection fatality rate, of 0.5-1%, have turned out to be basically right. And the latest serology surveys indicate only 5-10% of people in countries like the US, UK and Spain have been infected so far, leaving us far short of herd immunity. To get there, even these worst affected countries would need to endure something like ten times the number of deaths they have so far.

Marc has one good piece of news: research suggests that most of those who get infected do indeed develop immunity, for a while at least.

To escape the COVID-19 trap sooner rather than later, Marc recommends we go hard on all the familiar options — vaccines, antivirals, and mass testing — but also open our minds to creative options we’ve so far left on the shelf.

Despite the importance of his work, even now the training and grant programs that produced the community of experts Marc is a part of, are shrinking. We look at a new article he’s written about how to instead build and improve the field of epidemiology, so humanity can respond faster and smarter next time we face a disease that could kill millions and cost tens of trillions of dollars.

We also cover:

- How listeners might contribute as future contagious disease experts, or donors to current projects

- How we can learn from cross-country comparisons

- Modelling that has gone wrong in an instructive way

- What governments should stop doing

- How people can figure out who to trust, and who has been most on the mark this time

- Why Marc supports infecting people with COVID-19 to speed up the development of a vaccines

- How we can ensure there’s population-level surveillance early during the next pandemic

- Whether people from other fields trying to help with COVID-19 has done more good than harm

- Whether it’s experts in diseases, or experts in forecasting, who produce better disease forecasts

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type 80,000 Hours into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

Producer: Keiran Harris.

Audio mastering: Ben Cordell.

Transcriptions: Zakee Ulhaq.

Highlights

The true infection fatality rate in the US

I think it’s clearly under, say, one and a half percent, and it’s very likely under 1%. It’s clearly above 0.2% and probably above 0.4%. So I think if I really had to cover all my bases, I would say between 0.2 and 1.5, but I would put most of my money in the intermediate range.

I think one of the challenges is that it’s so variable by your risk factors, that a little bit of unrepresentativeness in the sampling of cases can translate into a really wrong inference about the death rate.

Immunity

I think there’s some slightly encouraging news that was published, I think, just yesterday in Cell by a large group of people, I think, mostly American researchers, that seems to show that the large majority of people create all three types of immunities through types of T-cells and antibodies and that essentially everybody that they studied creates an antibody response if you wait long enough.

So that’s a good sign. Of course, what we don’t know exactly is the degree of protection it offers, but we don’t know that for any new virus. We assume, in most cases, that there’s pretty good immunity. The only reason everyone’s hesitant with this one is that it’s a coronavirus and a lot of coronaviruses have sort of weak immunity, but I think all indications are that there will be some level of immunity in virtually everyone.

Human challenge trials

I think the resistance to it is that there is a very long tradition, unfortunately, of research that was done either with unwilling, non-volunteers or people who were under compulsion or in other unethical fashions. So research has been seen as an area where ethics have to be vastly more restrictive than in other activities that we do. I think in some ways that’s for very good reason, especially the reluctance of many physicians to be involved in deliberately giving someone an infection is an admirable trait. I think that on the other hand, in a situation like this where there is, as you say, massive social value to a trial, in expectation, of course a trial could fail. And some people have suggested that there’s no social value to finding out that a vaccine doesn’t work, but I disagree with that because we need to know which ones do and don’t work.

But I think in a situation like this with a large social value to doing such a study and the possibility that there really are thousands of people who have already stated their willingness to take on, actually in some cases, quite large risks… Some of them are not young and healthy, and they understand that that means that it is a risk. We should think of this as an activity like other altruistic activities that people engage in. It’s the nature of altruistic activities and of risky activities especially, that you don’t always know what the risk is. Someone doesn’t join the military on the grounds that they’ve been told that over history, 7% of military recruits have suffered some kind of bad outcome. I just made that number up. You join the military and, to the extent that that’s an altruistic decision, you decide, “I’m willing to take this risk because I want to serve a purpose that I believe in”.

Present uncertainties, and speak clearly

I’m a real fan of people who are very explicit about their sources of uncertainty and what their findings do and don’t imply for decision making. And I think that is characteristic of the people that I’ve just described. And it’s sometimes in competition with trying to get a splashy publication, but I think the best groups in our field have figured out a way to balance that and to say what they found but not to overclaim it. And just applying that filter of “Is there a good presentation of the uncertainties and the limitations” gets rid of a lot of garbage in the field. It’s not a perfect filter, but it’s a pretty good heuristic.

And I also think my doctoral advisor, Bob May, who died very recently, a couple of weeks ago, used to say, he was Australian so he said it with a little bit more color than this. He said, “If the freaking guy can’t explain that he doesn’t understand what he’s talking about, it’s not your fault”. And I also do see a very strong correlation between people who explain things clearly and people who are reliable. Because it’s harder to hide what’s really going on… I think a lot of people who do low-quality work don’t understand why they got the results that they got. They just got them and thought, “Oh, that’s exciting”. And the people who do high-quality work and can explain what they did I find much more credible. Because ultimately, all of this boils down to multiplication, division, and a little bit of calculus.

It’s not quantum physics. There are no truly counterintuitive things happening in our field. There are some things that are surprising when you first hear about them. We just worked through an exercise like that in my class right before I spoke to you. So there are things that are surprising, but there are no things that are so surprising you just say, “Well, the model says this and I don’t understand why”. So if you can’t explain it, you really don’t understand it. And those two heuristics together I think actually are a pretty good filter on work that’s likely to be meaningful.

Global catastrophic biological risks

I think that the most severe possible pandemics are either going to be addressable by the types of approaches that we develop for a pandemic like this one, or dealing with them is going to be pointless, and we’re just going to have a catastrophe. I don’t think that there’s a set of approaches that is distinctive to the utterly catastrophic scenario. I mean, this is in some ways close to catastrophic, but it’s not going to erase humanity. It will do a lot of damage economically and to health, but it’s not going to erase humanity or even a large fraction of humanity. But I think from a methodological perspective, this one is bad enough that we’re essentially throwing everything we have at it. There’s no extra thing that we’re saying, “Oh well we’re not going to do that, because this isn’t bad enough”.

We’re pretty much doing everything we know how to do. And moreover, less severe pandemics are more common because there’s been no pandemic to date that has wiped out the human race, by definition. And from a human resource perspective, again, the people who are going to deal with the problem in a catastrophic scenario, are the people who are dealing with this problem. They’re exactly the same people, and their successors. So the idea that I found hard to understand in some effective altruism discussions, is this idea that we know that all the minor cases are taken care of and we have to focus on the edge cases. But I don’t see any activity that would be helpful for the edge cases that doesn’t also involve preparing for the less edge cases like this one. I literally can’t think of one thing that is like that.

Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

Marc’s work

- General Principles for Choosing a Graduate Program or Postdoctoral Fellowship

- Covid-19 Path Forward website, by Joseph Allen, Barry Bloom, Caroline Buckee, Yonatan Grad, Bill Hanage, Marc Lipsitch, and Michael Mina

- Who Is Immune to the Coronavirus? in The New York Times

- Keep parks open. The benefits of fresh air outweigh the risks of infection. by William “Ned” Friedman, Joseph G. Allen and Marc Lipsitch

- Testing COVID-19 therapies to prevent progression of mild disease by Marc Lipsitch, Stanley Perlman, and Matthew K Waldor

- Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the post-pandemic period by Stephen M. Kissler, Christine Tedijanto,Edward Goldstein, Yonatan H. Grad, and Marc Lipsitch

- If a Global Catastrophic Biological Risk Materializes, at What Stage Will We Recognize It? in Health Security

- Good Science Is Good Science in The Boston Review

- Human Challenge Studies to Accelerate Coronavirus Vaccine Licensure by Nir Eyal, Marc Lipsitch, and Peter G Smith

- Defining the Epidemiology of Covid-19 — Studies Needed by Marc Lipsitch, David L. Swerdlow, and Lyn Finelli.

- Marc on Twitter

- Underprotection of Unpredictable Statistical Lives Compared to Predictable Ones

Everything else

- Do forecasting platforms beat expert predictions? Philip Tetlock comments. And read the latest expert surveys.

- Women in science are battling both Covid-19 and the patriarchy by Caroline Buckee et al.

- Adaptive cyclic exit strategies from lockdown to suppress COVID-19 and allow economic activity by Karin et al.

- 12th Annual Summer Institute in Statistics and Modeling in Infectious Diseases (SISMID)

- The 1 Day Sooner project for human challenge trials

- Identified versus Statistical Lives Edited by I. Glenn Cohen, Norman Daniels, and Nir Eyal

- How you can help with COVID-19 modelling by Julia R. Gog

- Reich Lab COVID-19 Forecast Hub

- Roadmap to Pandemic Resilience: Massive Scale Testing, Tracing, and Supported Isolation as the Path to Pandemic Resilience for a Free Society, by 21 authors

- National coronavirus response: A road map to reopening by Scott Gottlieb et al.

- Paul Romer’s plan

- What Is The Infection-Fatality Rate Of COVID-19? by Gideon M-K

Transcript

Table of Contents

- 1 Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

- 2 The interview begins [00:01:45]

- 3 Things Rob wishes he knew about COVID-19 [00:05:23]

- 4 Cross-country comparisons [00:10:53]

- 5 Any government activities we should stop? [00:21:24]

- 6 Lessons from COVID-19 [00:33:31]

- 7 Global catastrophic biological risks [00:37:58]

- 8 Human challenge trials [00:43:12]

- 9 Disease surveillance [00:50:07]

- 10 Who should we trust? [00:58:12]

- 11 Epidemiology as a field [01:13:05]

- 12 Careers [01:31:28]

- 13 Rob’s outro [01:36:40]

Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

Robert Wiblin: Hi listeners, this is the 80,000 Hours Podcast, where each week we have an unusually in-depth conversation about one of the world’s most pressing problems and how you can use your career to solve it. I’m Rob Wiblin, Director of Research at 80,000 Hours.

Professor Marc Lipsitch is a world-famous expert on emerging contagious diseases, including COVID-19, and is among the most-read epidemiologists on Twitter.

He’s getting a tonne of media requests every day so I felt both lucky and a bit surprised that he was willing to set aside a full 2 hours to answer my questions.

If, like me, you’ve tuned out of COVID-19 news, and want a quick way to get up to date, this episode will do that. And if you have somehow been keeping up, Marc has plenty of new views to share as well.

One notice before that. The Effective Altruism Global conference in SF had to be cancelled in March for obvious reasons, and we can’t yet know whether the London event in October will be able to go ahead.

But to fill the gap there’s a new online conference you can join next month between June 12 and 14 called EAGxVirtual. The main focus will be one-on-one meetings between attendees, but there’ll also be a bunch of live and pre-recorded content including talks, Q&As, speed meetings, and group discussions.

Presumably this won’t be as good as an in-person conference, but it will cost much less of your time and money. It’s being run on a ‘pay what you want’ with a suggested price of $40, which would allow them to cover their costs. And to go you won’t have to even catch a bus let alone a plane. So it could still be good value if you’re looking to make connection or find a way to have more impact.

It’s aimed at people who have some familiarity with ideas related to effective altruism, which probably includes you if you regularly listen to this show. You can apply to go at eaglobal.org.

Alright, without further ado, here’s Marc Lipsitch.

The interview begins [00:01:45]

Robert Wiblin: Today, I’m speaking with Marc Lipsitch. Marc is a professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He did his PhD at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar studying zoology, finishing in 1995, and later worked at the US Centers for Disease Control before joining the faculty at Harvard.

Robert Wiblin: He is an author of more than 200 peer-reviewed publications on antimicrobial resistance, mathematical modeling of infectious disease transmission, and development of immunity. His group produced one of the early assessments of the transmissibility of the original SARS virus in 2003, and has worked to estimate the transmissibility of the 1918 Spanish flu as well.

Robert Wiblin: He served on the President’s Council of Advisors Working Group on the H1N1 Influenza back in 2009, and has provided advice on antimicrobial resistance, SARS, and preparing for flu pandemics to governments around the world. The last few months, he’s been working to offer the best possible recommendations about the COVID-19 pandemic. Thanks for coming on the podcast, Marc.

Marc Lipsitch: Thank you for having me.

Robert Wiblin: You’ve been one of a handful of people that me and many others have turned to to understand what is going on with the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic via your Twitter presence, which has been a welcome source of sanity and technical expertise. So, it’s a privilege to get the chance to speak to you in person.

I hope we’ll get to talk about the latest COVID science and how we should be responding to the pandemic, but first, how’re you trying to help out with the anti-COVID effort at the moment?

Marc Lipsitch: Along a few different fronts, and, I mean, my primary occupation is I’m a scientist. I’m an epidemiologist. I see that as a broad set of responsibilities and areas to work in and so when we first saw in late January, early February as a group that this was starting to spread, I sort of urged our center to begin mobilizing and more so as the threat grew more obvious to do things that would be useful and that would be not necessarily the same thing others were doing.

Marc Lipsitch: One difference between now and the original SARS is there are dozens of really first-rate groups around the world that are doing good mathematical modeling. So, we tried to figure out what are the pieces that we could do that were more tied to work we were already doing or work that was slightly off the beaten path.

Marc Lipsitch: So we began with things like seasonality and trying to understand travelers and their impact. We’ve, as a group, begun from our center, working a lot on studying mobility and that as a proxy for social distancing. That’s mostly work that I’m not directly involved in, but that our center has done under the leadership of Caroline Buckee, a colleague of mine. My interests are very heavily with immunity and with vaccines and so trying to set up studies that will help us understand how immunity works better, so-called seroprotection studies, serologic studies to understand how the immunity is distributed in the population and how good it is. And then studies that could lead to a vaccine, and my work on advocating for human challenge trials of vaccines has been one aspect of that. And so that’s the sort of academic work.

Marc Lipsitch: And then, partly as a result of the peculiar situation in the US where the federal government is not taking on its traditional role as a supplier of good information that everybody can rely on because of political considerations, I, and a lot of my colleagues, have felt that one of our major roles can be to provide unbiased information about what we think is the best science. So, I’ve been doing that a lot through talking with journalists and through writing in the popular press.

Things Rob wishes he knew about COVID-19 [00:05:23]

Robert Wiblin: Okay. Great. We’ll return to some of those issues over the next couple of hours.

Robert Wiblin: But first up, I’ve somewhat given up staying abreast of the latest developments in the pandemic as it felt like it was kind of a full-time job that I gave up on, I guess, a month or two ago. And I think even if I tried, I would be getting so much wrong because I lack a lot of relevant training.

Robert Wiblin: So here, for maybe the first half an hour or hour, I just wanted to throw a bunch of somewhat technical questions at you, things that I kind of wish I had had the time to look into and get your take on where the evidence stands today, but I’ve got a lot of these, so feel free to pass if you don’t have much to add on any one of them. Sound okay?

Marc Lipsitch: Sounds good.

Robert Wiblin: All right. First up, what fraction of the US population has been infected with the virus so far?

Marc Lipsitch: Well, I think it’s really hard to say because in most places, we don’t have measurements. What has become clear from the measurements we have is it is extremely variable by location.

Marc Lipsitch: So Chelsea, Massachusetts has probably the highest seroprevalence or record of infection that’s been measured that I’m aware of, and that’s around 30% of the population studied. Other places are in the low single digits of percents where it’s been looked at. Even within New York City, when people have looked at prevalence of current infection, it’s quite variable by neighborhood.

Marc Lipsitch: So, it’s clear that to get a representative sample, we really are going to need to know a lot more. Having said that, I think it’s probably in the low tens of percents in the most, in certain dense urban areas, often in the low single digits or mid single digits in many other areas. And so I think overall, it’s probably in the high single digits of percents in the United States, but that could be wrong.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. I guess given that research that we’ve now started doing these seroprevalence surveys to try to figure out how many people have been infected, what do we now know about the true infection fatality rate in the US? Can we kind of put tighter bounds on it than we were able to a month or two ago?

Marc Lipsitch: I think we can. I think it’s clearly under, say, one and a half percent, and it’s very likely under 1%. It’s clearly above 0.2% and probably above 0.4%. So I think if I really had to cover all my bases, I would say between 0.2 and 1.5, but I would put most of my money in the intermediate range.

Marc Lipsitch: I think one of the challenges is that it’s so variable by your risk factors, that a little bit of unrepresentativeness in the sampling of cases can translate into a really wrong inference about the death rate.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Last I read an op-ed you wrote, you think that most people are probably going to have decent immunity against being reinfected by the same virus for at least, say, a year or two. Do you still think that’s the case based on research since then?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. I think there’s some slightly encouraging news that was published, I think, just yesterday in Cell by a large group of people, I think, mostly American researchers; I didn’t look at the whole author list, or I don’t know all the people, and that seems to show that the large majority of people create all three types of immunities through types of T-cells and antibodies and that essentially everybody that they studied creates an antibody response if you wait long enough.

Marc Lipsitch: So that’s a good sign. Of course, what we don’t know exactly is the degree of protection it offers, but we don’t know that for any new virus. We assume, in most cases, that there’s pretty good immunity. The only reason everyone’s hesitant with this one is that it’s a coronavirus and a lot of coronaviruses have sort of weak immunity, but I think all indications are that there will be some level of immunity in virtually everyone.

Robert Wiblin: That’s reassuring. Do you think the fatality rate and just general health damage that COVID does might be low enough that we should consider just letting most people gradually get the disease rather than doing what we’re doing now to try to prevent it from spreading?

Marc Lipsitch: Well, I think what we’re doing now to try to prevent it from spreading is letting people get it gradually, honestly, at least in the United States. I think it’s very different in other parts of the world in both directions but, at the moment, we don’t have a way to keep it really under control in the United States and I think it remains to be seen whether we can do better than… Control it more than just letting everybody get it gradually. I think probably the only places that can do better than that are islands, but, I mean, it clearly is mild in most people as far as we know. We don’t know what the long-term effects are. That’s an asterisk to anything we say about mildness, but I think we’re going to get to a point where we’re letting it spread slowly and we should try to make it spread as slowly as possible so that we protect more people with a vaccine or a treatment rather than fewer, and so delay is good, but I just don’t actually think it’s possible to just stop it at this point.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So I guess you think that by the time a vaccine or a more permanent satisfactory solution comes about, it’s probable that a large fraction of the US population will have had the disease?

Marc Lipsitch: I don’t know about large. I think if it’s about five or 10% now, I can’t envision a scenario where we have a vaccine or a really good treatment before it’s about twice that, but I think there’s just so much uncertainty in each of the pieces of that timing that it’s really hard to be precise.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. That’s really interesting. We’ll come back to that in some later questions.

Cross-country comparisons [00:10:53]

Robert Wiblin: Do you think we can learn much from cross-country comparisons at this point, or do you think they’re more often leading people astray?

Marc Lipsitch: I think they’re very helpful. In fact, I mean, of course testing whether that’s true or not remains to be seen. But in terms of forming hypotheses about what could be possible or feasible, I think, to me, the experience of South Korea and Singapore in trying to use contract tracing as the major control measure and, in Singapore’s case, losing control after a long period of seeming to have it under control, and in South Korea’s case, getting the case numbers down to very, very tiny numbers and then loosening social distancing with contact tracing in place and finding that that wasn’t good enough, to me, is very informative that this virus is just not easy to control by those measures, even in places that are perhaps two of the best suited countries in the world to make it work, if it’s doable.

Marc Lipsitch: The Prime Minister of Singapore went on Facebook very, very early on, I think in January or certainly early February saying, “We are likely to lose control of this.” And I think it was that level of realism that probably allowed them to keep control as long as they did.

Marc Lipsitch: I think those are informative. I think also that cross-country comparisons are informative for showing us what other Western democracies can accomplish with social distancing and for encouraging us to try to do better. I think also that international comparisons highlight a lot of what we don’t know or highlight that there are aspects of this that we just don’t understand. So we don’t know why India and Vietnam and Thailand and parts of Africa are suffering less from this than everyone expected. We have some hypotheses and it’s been written about and there’s lots of ideas, but the answer to that remains really confusing. I think it points to the fact that we need to understand aspects of immunity and of determinants of transmission by weather, by urban density and other factors, so it helps to point out some of the things we need to study better.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I think a style of analysis that I’m a little bit worried about is where people just pluck out a handful of US states or a handful of countries and then do comparisons of those saying, “Well, this country did well and it had this policy and this country did badly and had this other policy.” And they don’t kind of check by what they’re claiming would hold up if they looked across a much wider range of countries and didn’t just kind of pluck out a random subset of them. Do you also worry about that?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. I worry about, at least on a number of grounds. So the first is what you say, that you can find two data points that differ in interesting ways and spin a story, and that it may not hold up in a larger sample.

Marc Lipsitch: The second piece is that there’s clearly an element of luck here and that certain cities and countries got hit early. They had a lot of spread before they intervened and, in some cases, that was because of poor policy, but in some cases, that was because they just didn’t know it was there, like Wuhan, for example, and well, they knew it was there, but they didn’t understand the size of the threat. And so places that got big epidemics early before global recognition was widespread had bad luck and I think that’s an important piece of it.

Marc Lipsitch: Then, the last thing is there are a lot of people with a lot of agendas who are doing these comparisons, knowing the answer before they look at the data. I think that adds another layer of problems but, I mean, we have to use data. We don’t have anything else to do, but trying to take a scientific approach of seeing the signal and then being the one to point out all the aspects that might not be consistent with your theory before someone else does, I wish there was more of that.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. It’s the case where there’s so much unexplained variance that it’s unusually easy to spin narratives to prove whatever you want to prove.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I looked at the figures yesterday and, of the larger countries, it seemed like the UK had the fourth highest per capita COVID death rate and the US was actually the eighth highest, which probably overstates things because maybe there’s some other countries where the death rate is higher than it looks because they’re not measuring it very well. But it does seem like both countries have fared pretty poorly compared to overseas benchmarks. How do you explain that? Is it possible to do it at this point?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. I think in the case of the UK, I’m just less familiar with how it’s played out, although I sort of understand the broad strokes. I mean, in the United States, the total lack of a national strategy has cost lives and there’s just no other way to say it.

Marc Lipsitch: I think we have extraordinarily good people working in the top and middle and throughout the public health agencies. Their views have been sidelined largely in favor of an agenda to first pretend there was nothing going on and then to minimize it and to do all sorts of things that are really hard to imagine without being inside the President’s head. But you just can’t deal with a problem like this piecemeal and without a strategy.

Robert Wiblin: Mm-hmm (affirmative). What’s the biggest policy mistake that you’ve observed, I guess other than that one?

Marc Lipsitch: I think, and again, I, in general, am interested in everything that’s happening in the world, but I’ve been focused more on the US than I might have expected during a pandemic just because we have so many issues here and the need to try to contribute to public understanding here is greater than anticipated.

Marc Lipsitch: So I’m focusing on the US for a minute. I think sort of every piece of it follows from that overall lack of a strategy, starting with the failure to get testing up and running and the failure to sort of get everything up and running.

Marc Lipsitch: I was really the only person I knew who thought that President Trump’s decision to limit travel from China was a good idea. Everybody else said, “It’s not going to work and it’s just going to delay things a little bit at best.” And I agreed with them on that, but I thought a little delay could gain us a lot if we used the time. I hadn’t quite processed, as perhaps they had, that this was not the first piece of the policy. This was the policy. This was our approach to dealing with the problem.

Marc Lipsitch: So had we built up capacity for personal protective equipment and ventilators and hospital capacity and all that stuff in that extra time, it would have saved lives, but instead, we just closed the borders, proclaimed victory and said it would all be gone again. And so to me, it’s sort of all of a piece, but it’s not understanding that buying time is a valuable commodity and you’ve paid a big price for it so you better use it well.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. The weird thing I heard is that the US was just allowing American nationals to come back from China just straight through without going into any quarantine or any testing. It was only Chinese nationals, I think, who were getting blocked from coming back, which, I mean, obviously, doesn’t have a lot of… The virus does not choose who to infect based on their nationality.

Marc Lipsitch: Right. I think that’s because it was a tactic, not a strategy. It was an attempt to show we’re doing something rather than a piece of a strategy to make us safe from this virus.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. The IHME modeling has come in for quite a lot of criticism. Is there any interesting bad modeling that you’ve seen over the last few months that went wrong in an informative way?

Marc Lipsitch: Yes. There has been some. I do have another example. The issue with the IHME model is that it’s not an infectious disease model. It’s a curve-fitting model that doesn’t take into account infectious disease dynamics and so I just think of that as sort of in its category by itself of not very helpful, although extremely well-publicized. But the interesting modeling that I think has gone wrong, went wrong for a very technical reason that we’ve been actually trying to understand better, and that was a paper by Pan and colleagues, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, which concluded that the data from Wuhan that they were analyzing showed that the lockdown that happened on January 23rd was not enough by itself to reduce transmission to a point where cases began to fall instead of increase.

Marc Lipsitch: And so we’ve dug into the methods that they used. It turns out that they used a method for estimating the reproduction number, the number of secondary cases each case generates on a given day that’s a perfectly good method and, in some ways, the best of the methods, but it has to be timed in a certain way. You have to anchor the number that you’re estimating for each day very carefully and they did it in a way that was more naïve because at least some of the leaders of that project were not infectious disease modelers.

Marc Lipsitch: The conclusion was that only once they instituted involuntary out-of-home quarantine and isolation, was the epidemic brought under control. That then has been promoted by some of the authors as meaning that such a policy should be repeated everywhere and that most famously in an article in The New York Times by Jim Kim and Harvey Fineberg and one other collaborator, it said based on this Wuhan analysis, in part, that’s faulty, it said, “Americans are going to need to get used to involuntary family separation”. That struck me as sort of piling bad civic policy on top of bad science to get really bad outcomes. So to me that’s the worst example yet.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. It was interesting that recommendation because it seemed to kind of miss that, well, at least, before you were doing forcible quarantine, forcible separation, why not at least start by trying to encourage people to engage in voluntary separation and provide free accommodation for people who wanted to isolate themselves from their families to avoid infecting their loved ones? We weren’t even at that point, so it seems like at least you’d want to do that, like maybe pay people to do it before you started forcibly taking them out like they were doing in China.

Marc Lipsitch: Right. I mean, I think there are so many… That article also misinterpreted what had happened in Korea and Singapore. It was people that I very much respect making arguments that I thought were indefensible.

Any government activities we should stop? [00:21:24]

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So people are kind of always suggesting more things that we could do about COVID, but less often suggest things that we should stop doing so we could free up resources to actually be able to do these other things that would be more useful. Are there any kind of government activities that you think we should stop in order to free up attention for other things?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. I think we’re going to begin to learn more about that as different places open up in different ways. Near the beginning of the intense period in the United States, New York City was working very, very hard to do contact tracing at a time when they knew that they had lots and lots of cases and didn’t know about most of them. That’s exactly the setting where contract tracing can’t work, because no matter how hard you fight, the five or 10% that you know about, you’re not doing anything about the rest. That was in real time, diverting the health department from doing all the things that people in the health department wanted to do. Finally, the mayor of New York was convinced to stop insisting on this. That was very much what people in the whole department wanted to do, was get onto other activities.

Marc Lipsitch: So I think, in general, I’m a bit pessimistic about contact tracing as a mainstay of the policy. I think it’s an important thing to have in place and to try to use but I don’t, again, I think we have to throw many different approaches at this and that approaches that only target certain individuals are, by definition, very limited, especially in low information settings.

Marc Lipsitch: On a more sort of granular level, especially in Europe, there’s been a lot of closing of outdoor public spaces. I’ve written an op-ed and said a few times that outdoor transmission is just a lot less likely. It’s not that it’s not possible. It’s not that we shouldn’t social distance. But putting some resources, especially with so many people out of work, putting some resources into trying to keep social distancing happening in parks and in beaches even, rather than closing them off, seems like a much better trade-off because I think mental health is clearly going to be a big casualty in this response and being outdoors is really good for lots of things.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Closing outdoor spaces seems super misguided to me. It also means that you’ll lose public support for the stay-at-home message sooner because people will just find it intolerable if they can’t at least go outside to a park sometimes.

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. But I think a lot of countries have done that.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. What do you think of Sweden’s more laissez-faire approach?

Marc Lipsitch: I think it’s clearly killing more people than the neighbors. Having said that, I think that we’re almost all moving in that direction and that hopefully we can learn something from Sweden about what doesn’t work. But I think everybody is getting tired of being under restrictive policies and, I mean, Massachusetts so far has not reopened, but most states in the United States have begun to reopen and I think are heading in that direction. I think Sweden has, at great cost to themselves, demonstrated to the world that that’s costly.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. It’s interesting. Well, it seems like Swedes, despite the lack of government instructions are self-isolating a fair bit just off their own bat and traveling a whole lot less and, at the same time, their economy… So, their economy has contracted maybe more than you would expect given that the government hasn’t really ordered people to do that much and, at the same time, their health results are worse, but not way worse and I think it’s just maybe because, in fact, what they’re doing in reality is not that different than what their neighbors are doing.

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. I think that’s probably right. And I also wonder, a friend, we were having a discussion among our group by Zoom about Sweden and somebody said, “Well, my friend in Sweden is social distancing”. This next person said, “Well, my friend is”. I said, “Well, yeah. Of course all of our friends are social distancing because–

Robert Wiblin: They’re epidemiologists?

Marc Lipsitch: They’re students and… Well, yeah, so maybe they’re more aware but also, people who can do that because they’re students or office workers or whatever can do that.

Marc Lipsitch: But, I mean, another factor about Sweden is that although it’s changing, I guess, recently, they do not have the levels of inequality that some other places have like the United States. In places with concentrated wealth inequality, there’s also concentrated health inequality of all the kinds of conditions that predispose people to bad outcomes with COVID. So I don’t know how to quantify that, but it must be a part of the story as well.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Do you have a view on making and wearing homemade masks?

Marc Lipsitch: My daughter’s made dozens of them and we wear them. I mean, I think the limited data suggests that they are protective for other people. Not perfectly protective. I can’t say that I enjoy it. It really is quite unpleasant, but compared to other types of ways of slowing down virus transmission, it’s probably one of the more tolerable ones. So I think it should be compulsory outside. I mean, not outside necessarily, but–

Robert Wiblin: Indoors. In public indoor areas.

Marc Lipsitch: Right. In public areas and probably some outdoor areas.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. My impression is that public discourse focuses a lot on vaccines, maybe because they’re easier to explain and it’s really nice if you can get there, but we may not have a vaccine for years and, I guess, possibly never.

Robert Wiblin: So, do you think we need to maybe put more attention into drug treatment or perhaps testing, tracing and isolating people, or maybe finding a way to continue in a somewhat normal life without allowing that much transmission, kind of as alternative exit strategies to the stay-at-home orders?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. I mean enough is at stake here that we should be trying everything we can on all of these fronts. I mean, a quarter of the economy is a lot of the economy and we’re not done yet.

Marc Lipsitch: So I think it’s clear that we need to push on all these fronts because even if we do get a vaccine, it will take a while to scale it up and it will take and there will be some hiccups along the way.

Marc Lipsitch: So clearly we need a lot of creative thinking about alternative ways to make life go on. I haven’t seen any really brilliant ideas that seem doable yet, but I think there are a number ideas that may have aspects that work.

Marc Lipsitch: And one that I kind of like, although it’s got plenty of issues also, is this sort of four days on, 10 days off working approach to try to essentially get it out of sync with the virus transmission.

Marc Lipsitch: This is a group of Israeli investigators who have proposed that. And to me, the one hole to that is the 10 days off would be then transmitting to people at home.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Seems like a big weakness.

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. But that kind of thinking is very much to be encouraged.

Marc Lipsitch: On the drug front, I’ve been advocating, along with several colleagues and there’s now a nonprofit that’s funding this, a real need for drugs that are effective against early infection and mild infection to prevent it from getting severe rather than only looking for drugs that can save severely ill people from death or intensive care. There’s a good rationale that most antiviral drugs work better in the early phases of infection as we’ve seen from many other treatments and you could help a lot more people and reduce the burden on hospitals. So I think that’s a pretty straightforward modification to how we study things that would be very valuable. There’s a group called treatearly.org that’s raised money to try to fund such trials.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. You said you’re in favor of creating thinking here so, I guess, should we consider variolating people with tiny doses of the virus, which is kind of a strategy that historically, or there’s some evidence that it produces a much more mild illness, so you could potentially get immunity without that many people dying?

Marc Lipsitch: I think it’s worth considering. As you know, I put a lot of effort into a different controversial idea and I think I might stop with one as being a primary advocate, but I think this is a serious possibility. I’ve heard it proposed by very thoughtful and knowledgeable people and I think it’s worth considering.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. Yeah. We’ll return to the other controversial idea later on.

Robert Wiblin: There’s a bunch of reports out there which all feature a big scale-up in testing, including “Roadmap to Pandemic Resilience” which had 21 authors, Scott Gottlieb’s “National coronavirus response: A road map to reopening”, and Nobel Prize winner Paul Romer has been promoting a plan to test everyone in the US on a periodic cycle of a week or two, I can’t recall exactly. We’ll put up a link to all of those though. Do you have thoughts on these proposals?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. What I can say about all these testing-based plans is we need to scale up testing for every possible way forward. There’s no approach that makes sense that doesn’t involve considerably more testing. How we deploy that testing… I think there are a lot of ideas and a lot of creative ideas. I like the idea of using testing rather than long-term quarantine for contacts, which is one of the aspects of the Roadmap to Pandemic Resilience. I think that’s a good idea, although it would take enormously more amounts of testing if the contact tracing was effective.

Marc Lipsitch: So I think it’s good that people are trying to think through all these things. I think every plan has limitations and that’s not because people aren’t doing a good job. It’s because this is a problem that doesn’t have a perfect solution.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I noticed that you and some colleagues had made a website, covidpathforward.com, as a way of kind of keeping up with the views that you’re forming on policy and behavioral issues. Is there anything you want to say about that project?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. I think we took a broader, but in some sense, less comprehensive view, or in one sense more comprehensive, where we thought there were some things that we could agree upon. There are now 14 points in there ranging from massive upscale of testing, which I just mentioned, to the latest one is healthier buildings, which the instigator of this website, Joe Allen is an expert on, to use of masks as a prevention measure.

Marc Lipsitch: I don’t think that this amounts to a comprehensive plan, but it’s the sort of overlap, in my view, of all the sensible things that we’re aware of that people have been proposing and that together will make a difference in helping to control this virus. But I think there are still many more things to be worked out.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Do you worry that suggesting so many things maybe lacks prioritization and could mean that people’s efforts are a bit too diffuse or maybe is it a good idea to just throw everything at people and then they can pick up whatever part of the set of suggestions they’re capable of implementing?

Marc Lipsitch: Well, I think a lot of these are relatively minor things. I mean, wearing a mask is unpleasant and I don’t like it, but it’s not like a wild change in life and testing is not something people need to do. It’s something that employers and policymakers need to do. So it’s certain kinds of people, but not everybody. I think going back to the idea of having a strategy; a strategy has many tactics. I think there’s no way to fight this virus without doing many, many different things. So, that’s why we tried to highlight the ones that are essentially relatively low cost, in fact, most of them, scaling up testing is maybe more costly, but certainly worth it. But a lot of the alterations to buildings, for example, are in the few dollar range up to the few hundred dollar range for a small building and more for a larger building, but these are not crazy ideas. These are sort of small improvements that we can make that together will add up to something.

Lessons from COVID-19 [00:33:31]

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. What would be the wrong lesson to take from COVID in terms of managing future pandemics?

Marc Lipsitch: It feels a little early to be drawing lessons because we don’t know how the story ends but, I mean, I think the right lesson to draw is that early response really, really matters. That is really the strongest correlate that I can see of who’s had worse and better outcomes so far. That that involves sometimes overreacting, and so there will be cases where you react to something and it doesn’t materialize as a big threat, but I think we can see the costs of letting something get out of control.

Robert Wiblin: Speaking of reacting early, is it realistic that if China had been really on the ball and tried to control this thing as soon as they found out about it, maybe in late December, or they had better monitoring so they could find out about a new virus spreading earlier, that we could have prevented it from becoming a pandemic and save tens of trillions of dollars?

Marc Lipsitch: I don’t think we’ll ever know for sure, but it’s completely clear that small epidemics are easier to control than big ones. That’s almost so obvious, it’s not worth saying. And at some point, this was small. So, I think the question is if it had been three people or eight people and those people that been isolated adequately, then we might have been spared this. But it’s really hard to say.

Marc Lipsitch: I mean, I think probably the best answer to that is Singapore ultimately didn’t control it despite having more advanced warning and smaller numbers of cases early on and extremely good public health. New Zealand may be the greatest success story. So maybe if China had replicated New Zealand, but I’m not sure if China could have replicated New Zealand because it’s not an island and it’s not–

Robert Wiblin: Sparsely populated.

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. And there’s a lot of things in New Zealand’s favor. So, I think that’s probably the best answer is “No, it wouldn’t have worked because nobody else was able to control it with even earlier interventions”.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. That’s very interesting. I guess often people say, “Well, the way to stop pandemics in future is to control them at the outset and prevent them from getting out of hand with a very fast response”, but I suppose maybe that works on diseases that are less contagious than this one.

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. It’s probably on the borderline. So, I mean, I guess the wrong lesson to take would be–

Robert Wiblin: It’s impossible.

Marc Lipsitch: –Don’t try. It’s impossible because every disease is different and there’s still controversy about how exactly contagious this disease is.

Robert Wiblin: It seems like everyone who has any database, or any set of data that could possibly be related to COVID is trying to run a bunch of regressions. I’ve seen headlines from everything about, the BCG vaccines, to the gender of your head of state as being a potential important factor in the country’s performance in controlling COVID, which looks like a multiple hypothesis testing nightmare. Do you think there’s any… I guess there’s a lot of regressions being run that haven’t been published even. So is there any way of leveraging all that information out there without also just suffering massive parallelized p-hacking on a global scale?

Marc Lipsitch: That sounds like a really catastrophic state of the world: massively paralyzed p-hacking. I think broadly speaking, and this is not always true, but broadly speaking, these regressions are hypothesis generating. And in that sense, the more the better, and then somebody needs to decide what’s worthy of following up. But I don’t mind if someone does an observational study that suggests the BCG vaccine is protective. And I know very sensible people who are doing randomized trials now to find out if the BCG vaccine is protective. So that’s an example where it seems far-fetched, and the cost of being wrong is a small trial, but that tells you you were wrong. So I think there’s not a huge risk in having all these multiple comparisons made, as long as they’re interpreted sensibly as–

Robert Wiblin: Just as possibilities.

Marc Lipsitch: Possibilities, yeah. And I think this gets to what I said in the Boston Review last week, or this week, is that we need different kinds of evidence. Not all evidence is going to be of high quality, and we have to make decisions and try very hard to make our quality of evidence better, so we make better decisions in the future. But I think the profusion of hypothesis doesn’t bother me as long as they’re clearly demarcated as hypothesis.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah.

Global catastrophic biological risks [00:37:58]

Robert Wiblin: You’ve written at least one paper mentioning global catastrophic biological risks, which was called “If a GCBR Materializes, at What Stage Will We Recognize It”? And regular listeners will know that GCBRs are a particular interest for us at 80,000 Hours, because we kind of easily imagine a pandemic that’s as contagious as SARS-2, but with 10X or even 50X the fatality rate of this one. Given that, do you think it’s sensible for emerging disease experts to focus more on the most severe possible pandemics? Or do you think they already get an appropriate level of attention?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah, I think that the most severe possible pandemics are either going to be addressable by the types of approaches that we develop for a pandemic like this one, or dealing with them is going to be pointless, and we’re just going to have a catastrophe. I don’t think that there’s a set of approaches that is distinctive to the utterly catastrophic scenario. I mean, this is in some ways close to catastrophic, but it’s not going to erase humanity. It will do a lot of damage economically and to health, but it’s not going to erase humanity or even a large fraction of humanity. But I think from a methodological perspective, this one is bad enough that we’re essentially throwing everything we have at it. There’s no extra thing that we’re saying, “Oh well we’re not going to do that, because this isn’t bad enough”.

Marc Lipsitch: We’re pretty much doing everything we know how to do. And moreover, less severe pandemics are more common because there’s been no pandemic to date that has wiped out the human race, by definition. And from a human resource perspective, again, the people who are going to deal with the problem in a catastrophic scenario, are the people who are dealing with this problem. They’re exactly the same people, and their successors. So the idea that I found hard to understand in some effective altruism discussions, is this idea that we know that all the minor cases are taken care of and we have to focus on the edge cases. But I don’t see any activity that would be helpful for the edge cases that doesn’t also involve preparing for the less edge cases like this one. I literally can’t think of one thing that is like that.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So I’m inclined to agree with you, but what about things like regulation of dual-use research, or how we deal with biological weapons programs. Those things seem a bit more distinctive potentially to worst-case scenarios and less towards natural pandemics. Although I suppose maybe the split here is between natural pandemics versus anthropogenic ones.

Marc Lipsitch: Right. Well I think dual-use research is, as you know, a concern that I’ve been very active in and I do think it’s important, but it’s important not only because it could create a pandemic 50 times worse than this one, but because it could create a pandemic–

Robert Wiblin: Like this one.

Marc Lipsitch: Like this one.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, interesting.

Marc Lipsitch: And that’s not taking a position on where this virus came from. That’s not my point. My point is, this is really bad and trying to prevent this is a worthy outcome. And of course it’s better. It’s even a bigger benefit if we can prevent the others. But I don’t see dual-use research as an issue of preventing catastrophe only. It’s an issue of preventing things along the spectrum to catastrophe.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. That’s very interesting. I guess the weapons programs potentially still stand out as something that’s a bit unusual where perhaps it’s more focused on a disease where there’s been some intention to try and make it more dangerous, which doesn’t occur otherwise. And that’s a somewhat unusual case, although fortunately there aren’t that many biological weapons programs that active out there.

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. But again I think there’s no activity that’s… I mean yes, biological weapons are a problem, but you can think of it as dual-use solutions that anything that’s beneficial against catastrophic risks, will be more beneficial, both because it’s more likely to be effective, and because it’s more likely to materialize against smaller, but still gigantic risks like this one.

Robert Wiblin: I guess one thing that’s potentially distinctive about a GCBR is that we would be willing to pay an even higher price than what we have with COVID. So you can imagine, for example, that just months and months of a full lockdown like they did in China, in a wider range of countries, would become a tolerable option potentially if it had a 10% or 50% fatality rate. It’s probably clear that we would try to do that. And so exploring that potentially looks a bit different.

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah, and I think that’s reasonable. But I don’t think we need a hundred million dollars to do that. I think we need some relatively modest investment in those edge cases, but that each investment in COVID-like prevention and response will pay equal dividends for those types of things.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I was going to say, if you’re going to write more papers on GCBRs, what might they be about? Sounds like it might be similar to the other things that you’re doing.

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah, I don’t know. I wrote that in part as a version of a talk that I gave at one of the effective altruism conferences where my point was essentially this: that a deliberate weaponized release where we get to GCBRs, is to fail to contain something smaller.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah.

Human challenge trials [00:43:12]

Robert Wiblin: All right. Let’s talk about human challenge trials for a minute — this controversial idea that you mentioned earlier. So you’ve been promoting a project called “1 Day Sooner”, or you’ve written papers related to them. The project is encouraging these human challenge trials which involve deliberately infecting healthy, young volunteers with SARS-CoV-2 in order to test the effectiveness of vaccine candidates and thereby speed up their development. It’s a little bit risky for the volunteers, but not that risky for the healthy, young people you’d be doing it with and that have access to top medical support. And when I’ve done the back-of-the-envelope calculation, it just seems like an obviously good idea because you could save thousands or tens of thousands of lives probably without even a single willing volunteer dying of COVID. I guess I’ll give you a softball. What’s the least bad argument against doing human challenge trials? Maybe other interviewers will be skeptical, but it just feels to me like a very good idea.

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. I mean, I think the resistance to it is that there is a very long tradition, unfortunately, of research that was done either with unwilling, non-volunteers or people who were under compulsion or in other unethical fashions. So research has been seen as an area where ethics have to be vastly more restrictive than in other activities that we do. I think in some ways that’s for very good reason, especially the reluctance of many physicians to be involved in deliberately giving someone an infection is an admirable trait. I think that on the other hand, in a situation like this where there is, as you say, massive social value to a trial, in expectation, of course a trial could fail. And some people have suggested that there’s no social value to finding out that a vaccine doesn’t work, but I disagree with that because we need to know which ones do and don’t work.

Marc Lipsitch: But I think in a situation like this with a large social value to doing such a study and the possibility that there really are thousands of people who have already stated their willingness to take on, actually in some cases, quite large risks… Some of them are not young and healthy, and they understand that that means that it is a risk. We should think of this as an activity like other altruistic activities that people engage in. It’s the nature of altruistic activities and of risky activities especially, that you don’t always know what the risk is. Someone doesn’t join the military on the grounds that they’ve been told that over history, 7% of military recruits have suffered some kind of bad outcome. I just made that number up. You join the military and, to the extent that that’s an altruistic decision, you decide, “I’m willing to take this risk because I want to serve a purpose that I believe in”.

Marc Lipsitch: Similarly, for police and fire, and I think perhaps most strikingly, the people who have jumped into their medical residencies early in the middle of COVID. Those are people who are very deliberately saying, “I had no prior obligation to do this, but I’m going to take on a risk of being a healthcare worker because I want to help in this problem”. I think it’s unfortunate to deny people who want to play a different role as a volunteer the chance to do that. But I’m very sympathetic and very much agree with the people who think research needs to be treated very carefully. I just think that has to be modulated by the risk and benefit.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, it seems pretty perverse to allow people to take on probably a greater risk just to work at a checkout at a supermarket than you would allow someone to take on in order to potentially speed up the development of a vaccine, which seems like it’s more important. I suppose we do just have these different standards for research than for practically any other behavior.

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah, I think it’s partly that, and I think it’s also that if the trial is designed well, some of the people in the trial are almost certain to get infected. So we also had this whole strange approach philosophically to statistical versus deterministic lives. So I think that’s also part of it. Actually, I think a big part of it is also the fact that healthcare professionals, doctors, and nurses are going to be involved in these trials just by the way they’re set up. The notion that you’d take off your physician’s role and put on the researcher role and that those are really different, and that your duties are different in those roles, I think it’s hard for anyone to get their head around. I don’t think it’s a weakness. I think it’s just part of humanity that we have a hard time compartmentalizing. It’s probably a good thing mostly that we do, but in this case, I think it can keep people from doing something that would be valuable.

Robert Wiblin: Do you think human challenge trials will ultimately happen?

Marc Lipsitch: I think it’s looking increasingly likely that they will in the sense that the ethical statements that have been made now by quite diverse and authoritative groups, the World Health Organization and elsewhere, are more permissive than I might have imagined at first and are very much encouraging the development of the framework to do this. I’m also encouraged that a lot of policymakers have begun to say that this is an important option.

Marc Lipsitch: I mean, in some ways, one thing I would say is that I don’t really have a desire for human challenge trials to happen in the abstract. I want them to be a possibility, but it’s not that I have a special desire for that to be the way that a vaccine is licensed or is pushed forward. I would like it to be pushed forward in the fastest, ethical, and scientifically valid way, and I think this might be that. But in some sense, I do hope that they happen in that, if they happen, it will be because a Phase 3 trial is not practical to do in a very quick way because there aren’t places with very high incidents of the disease where the trial could be done. So it would indicate that we’ve controlled things well, at least in the places where we are contemplating trials.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Well thanks for being willing to speak up in favor of this idea, really. And, I guess, also thanks to the 20,000 people who’ve already put their names down for potentially participating in a human challenge trial. It’s, I think, a very good sign about someone that they’re willing to do that.

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah, and I should say just about the 1 Day Sooner; we weren’t promoting 1 Day Sooner and, as far as I know, they didn’t exist at the time we wrote the article. I think what happened is that when we wrote the article, Josh Morrison and Sophie Rose and a few others created 1 Day Sooner. I don’t actually know the whole causal chain, but I think it went the other direction, if I’m not mistaken.

Robert Wiblin: Nice. Yeah, we’ll stick up a link to 1 Day Sooner as well as your paper.

Disease surveillance [00:50:07]

Robert Wiblin: Let’s discuss disease surveillance for a second. It would have been really useful to have population-wide, randomly sampled testing back in February, possibly even January, to try to figure out how widespread SARS-2 was in different places and try to pin down what the actual infection fatality rate was. It’s kind of crazy to me that we got to the point of shutting down our economies at a cost of tens of billions of dollars a day and this still, at that point, hadn’t been done anywhere. That could have revealed that the infection fatality rate was much lower than we thought, and so we were making a massively costly mistake.

Robert Wiblin: As it turns out, it doesn’t seem like that was the case. The IFR is decently high. It was about where we thought it was, but we could have made a mistake. But no one was willing to use these testing kits to test randomly selected people, as far as I could see it, even though the information it would produce could potentially save far more lives in the bigger picture than testing someone who has COVID-like symptoms. Do you agree what would make sense at a global or national level to reserve some tests for randomly selected people for surveillance purposes?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah, and I’ve written that in the New England Journal in February or March. I don’t remember when it came out. I think it might’ve even been January. I think it was February. That we should be wasting a lot of tests, “Doing surveillance to try to understand the extent of infection”. I think it would have been, in retrospect, it would have not worked that well to do it with viral tests because, well, unless we had done it truly with a random cross section of the population because the proportion asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic was so high.

Marc Lipsitch: So we would have had to be prescient about the types of people to test which we weren’t. At least I wasn’t at that time. In general, the idea of having some random testing is clearly very important. Had we have done it with serology, we would have solved that problem, but had a different problem, which is that the specificity of the serologic test is not perfect. So, with low prevalence, we would have had a lot of false positives. I don’t have a really good “after the fact we should have done such-and-such” idea because, in fact, we might’ve been misled even if we had done all of that.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Maybe I’m not quite understanding. It seems like if in this case we’d done thousands of PCR tests on randomly selected people across the United States, we would have, I guess, in February found out that there was some people who had it, but it wasn’t super common. It wasn’t as if it was spreading everywhere, but we were at the beginnings of a pandemic at that point. Which seems like it would have been really helpful because then we potentially would have brought forward a bunch of their response because people were kind of sleepwalking into a disaster at that point. And it would have prevented this long discussion about, “Oh, is the infection fatality rate in fact really low because tons of people have had it”? It would have shown that that’s not the case. Or am I not right about that?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. I think that discussion was more in March, if I’m not mistaken. That might be a mistake.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. But it would have made that unnecessary.

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. I’m just trying to think. I don’t really know how many people had it in the US. Whether thousands would have really picked up very much in a statistically meaningful way.

Robert Wiblin: I see. Ah, so you think we might’ve been misled by getting a result that nobody had it. But in reality there were some clusters starting in various places and we were in a dangerous situation?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah, I think we could have easily missed it. Although, I mean, it would have been better than no data, but I’m not sure it would have settled the issue.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Do you think that we should try to do things to make this surveillance happen sooner next time?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. I mean we certainly should. We certainly should find a more reliable way to make sure that we have testing kits. One of which is to just follow the WHO’s recommendation and not try to be too clever in creating the kits as we did in the US. Another thing is clearly we have a reagent supply chain problem that needs to be fixed both by decentralizing it so that the reagents can be made in multiple places, and we’re not relying on one, and by expanding the capacity. So I think that the harder thing that I think a little bit of ingenuity probably could solve, I just don’t know how to solve it now, is trying to have a system in place so that you can get to 10,000 randomly selected people or 100,000 randomly selected people in a way that’s not heavily biased by whether they think they’ve had the infection already. I think that’s a big problem in a lot of the surveys that have been done so far, but that, I think, is a solvable problem. It’s just not a solved problem yet.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. As far as I know, no country used what testing capacity they had, admittedly limited testing capacity in February, for this population level of surveillance. Some started doing it a bit in March. Am I right in understanding that the barrier to that is that, I guess, in terms of forming national policy or in terms of protecting the population as a whole, what you need is the surveillance? But then the healthcare system is very focused on this clinical mindset of, “How do we help the patients in front of us or the patients who are coming in the door that are sick”, and they don’t perhaps think about it at the same systematic level where you’re thinking about, “How do we stop the pandemic, or how do we get the right policy in place at the right time”? And so that ends up dominating the rationing of the tests.

Marc Lipsitch: I think that’s right, and that’s why we put a line in our paper and knew in February about the need to allocate some tests for this purpose. So, I fully agree with you, but I think it also was that there was not an infrastructure for doing it easily.

Robert Wiblin: I see. Okay. So you think perhaps the next limiting factor would be that we wouldn’t have a good process for truly randomly selecting people across the country to be tested?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. I mean, we’ve been trying to think of this for serologic testing, and especially for something that involves sticking a swab in your nasopharynx, like virus testing, or pricking your finger for blood. It’s just not something that everybody is desperate to do, surprisingly enough. So you do get biases in who is willing to do that. So talked about door-to-door type of approaches.

Robert Wiblin: What about paying people? Pay them each a hundred bucks.

Marc Lipsitch: Paying them would work. I think that’s a good idea. In Spain they just did a big serosurvey, and they put the census agency or the statistics agency in charge of it. People were sort of stalked until they made contact, and they made an appointment and said, “Well, we’ll be there at your house to do this”. So there are ways to do it. It’s just it’s hard if you’ve never done it before, and you’re not being supported from above. There’s a thing called the American Community Survey that’s part of the census that would be excellent for this but has very slow moving wheels.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Yeah, I know some people who’ve been trying to do this, and the number of practical hurdles is substantial. It’s the kind of thing where you really want to set up the infrastructure ahead of time, otherwise you just get delayed a couple weeks. Is there any way maybe of setting things up ahead of time such that whatever organization has the nation’s or the whole population’s interests at heart rather than a patient in front of them, at the front of their mind, that they get access naturally to testing capacity so they can then use it for this purpose rather than they have to go begging for it and then it’s refused?

Marc Lipsitch: Right. Well, that might be the CDC in a normal time. It was the Statistics Agency of Spain and I think the census or some equivalent in the UK has been doing a serologic study. So there is such an agency. It’s just that they’ve been sidelined in this.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I guess another option would just be to massively increase the standby testing capacity that we have so the rationing isn’t as severe early on in the pandemic, and people feel more flexibility to take a thousand to do these surveys.

Marc Lipsitch: Right. I think that’s true, and much of that can be done in advance. But the exact kits need to be generated in response and, as we saw, that doesn’t always go right.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I guess, well, there’s some more flexible things, like nanopore sequencing, which seems like it might be possible to totally readapt it to a new disease. It seems kind of cool.

Marc Lipsitch: Well, it’s possible to readapt a PCR to a new disease. You just have to do it right.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah.

Marc Lipsitch: I mean, there’s nothing technically that hard about it. It was just a mistake.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah.

Who should we trust? [00:58:12]

Robert Wiblin: All right, let’s talk about how people can figure out what to believe about COVID-19 and other new diseases as they emerge. I guess true experts, by definition, are the people that you should listen to, but it seems like it’s a little bit still up for grabs who’s going to turn out to have been the best experts to listen to on COVID-19. Have you learned to update your views more in response to some kinds of sources and less in response to others over the last couple of months?

Marc Lipsitch: Yes, and with the exception of sort of people who are quite junior in the field who I just didn’t know as well, I’m afraid it’s reinforced my views that people who have been in this business for a long time are really more reliable, and that a Nobel Prize doesn’t make you an expert in this. And that being at a prestigious university in Silicon Valley doesn’t make you an expert in this. And that the intersection of those two doesn’t make you an expert in this. And that, once again, in my opinion, the most important work, a lot of it, has been done putting aside any self-dealing and self-evaluation. I would say in Hong Kong, from the group that’s been working on these things for 20 years since SARS. At the London School at Imperial College, at the RIVM in the Netherlands a little bit less just because it’s a smaller group, but they continue to do excellent work, and in a few other places. And then there are some new voices that are doing important work who just are newer to the field. And it’s really not mostly people coming in from outside, in my opinion. And I’m sure I have a little bit of bias, but I think much of that bias is justified.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, interesting. So how would we identify these people? I guess you’re sort of saying maybe next time we should just look for people who’ve been doing contagious disease epidemiology for decades and they’re going to have a lot of booted up knowledge that will allow them to reach the right answers faster?

Marc Lipsitch: Yeah. And I’m a real fan of people who are very explicit about their sources of uncertainty and what their findings do and don’t imply for decision making. And I think that is characteristic of the people that I’ve just described. And it’s sometimes in competition with trying to get a splashy publication, but I think the best groups in our field have figured out a way to balance that and to say what they found but not to overclaim it. And just applying that filter of “Is there a good presentation of the uncertainties and the limitations” gets rid of a lot of garbage in the field. It’s not a perfect filter, but it’s a pretty good heuristic.