Tara Kirk Sell on COVID-19 misinformation, who’s done well and badly, and what we should reopen first

By Robert Wiblin and Keiran Harris · Published May 8th, 2020

Tara Kirk Sell on COVID-19 misinformation, who’s done well and badly, and what we should reopen first

By Robert Wiblin and Keiran Harris · Published May 8th, 2020

On this page:

- Introduction

- 1 Highlights

- 2 Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

- 3 Transcript

- 3.1 The interview begins [00:01:43]

- 3.2 Misinformation [00:05:07]

- 3.3 Who has done well during COVID-19? [00:22:19]

- 3.4 Guidance for governors on reopening [00:34:05]

- 3.5 Collective Intelligence for Disease Prediction project [00:45:35]

- 3.6 What else is CHS trying to do to address the pandemic? [00:59:51]

- 3.7 Deaths are not the only health impact of importance [01:05:33]

- 3.8 Policy change for future pandemics [01:10:57]

- 3.9 Emerging technologies with potential to reduce global catastrophic biological risks [01:22:37]

- 3.10 Careers [01:38:52]

- 3.11 Good news about COVID-19 [01:44:23]

- 3.12 Rob's outro [01:51:02]

- 4 Learn more

- 5 Related episodes

…we all went into lockdown at incredible cost to ourselves right now, and to our kids in the future… and still six weeks go by and I don’t see huge improvements in testing capacity, in serology, in PPE, in hospital capacity. These things just haven’t happened…

Tara Kirk Sell

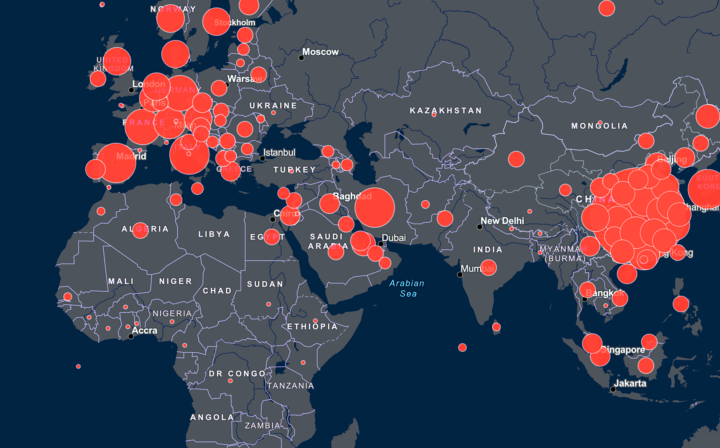

Amid a rising COVID-19 death toll, and looming economic disaster, we’ve been looking for good news — and one thing we’re especially thankful for is the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (CHS).

CHS focuses on protecting us from major biological, chemical or nuclear disasters, through research that informs governments around the world. While this pandemic surprised many, just last October the Center ran a simulation of a ‘new coronavirus’ scenario to identify weaknesses in our ability to quickly respond. Their expertise has given them a key role in figuring out how to fight COVID-19.

Today’s guest, Dr Tara Kirk Sell, did her PhD in policy and communication during disease outbreaks, and has worked at CHS for 11 years on a range of important projects.

Last year she was a leader on Collective Intelligence for Disease Prediction, designed to sound the alarm about upcoming pandemics before others are paying attention. Incredibly, the project almost closed in December, with COVID-19 just starting to spread around the world — but received new funding that allowed the project to respond quickly to the emerging disease.

She also contributed to a recent report attempting to explain the risks of specific types of activities resuming when COVID-19 lockdowns end.

It’s not possible to reach zero risk — so differentiating activities on a spectrum is crucial. Choosing wisely can help us lead more normal lives without reviving the pandemic.

Dance clubs will have to stay closed, but hairdressers can adapt to minimise transmission, and Tara (who happens to also be an Olympic silver medalist swimmer) suggests outdoor non-contact sports could resume soon at little risk.

Her latest work deals with the challenge of misinformation during disease outbreaks.

Analysing the Ebola communication crisis of 2014, they found that even trained coders with public health expertise sometimes needed help to distinguish between true and misleading tweets — showing the danger of a continued lack of definitive information surrounding a virus and how it’s transmitted.

The challenge for governments is not simple. If they acknowledge how much they don’t know, people may look elsewhere for guidance. But if they pretend to know things they don’t, or actively mislead the public, the result can be a huge loss of trust.

Despite their intense focus on COVID-19, researchers at the Center for Health Security know that this is not a one-time event. Many aspects of our collective response this time around have been alarmingly poor, and it won’t be long before Tara and her colleagues need to turn their mind to next time.

You can now donate to CHS through Effective Altruism Funds. Donations made through EA Funds are tax-deductible in the US, the UK, and the Netherlands.

Tara and Rob also discuss:

- Who has overperformed and underperformed expectations during COVID-19?

- When are people right to mistrust authorities?

- The media’s responsibility to be right

- What policies should be prioritised for next time

- Should we prepare for future pandemic while the COVID-19 is still going?

- The importance of keeping non-COVID health problems in mind

- The psychological difference between staying home voluntarily and being forced to

- Mistakes that we in the general public might be making

- Emerging technologies with the potential to reduce global catastrophic biological risks

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type 80,000 Hours into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

Producer: Keiran Harris.

Audio mastering: Ben Cordell.

Transcriptions: Zakee Ulhaq.

Highlights

Misinformation

Misinformation is something that we see all the time and we’ve also seen these disinformation campaigns that have really started to move into public health. There was a paper in AJPH about Russian trolls and the vaccine debate. So I’m not surprised that we’ve seen this level of misinformation and disinformation in this outbreak. I’m glad that people are paying more attention to it. I think it is a huge opportunity to sow division in the American public and lead to a lot of lack of trust which to me is really concerning. So I think the themes we saw for the Ebola outbreak, we see those exact same things now. You could almost just take the disease name out and replace it and you see many of those same themes. So that wasn’t surprising. But the extent to which we’re seeing it, I guess, is something that’s new and interesting.

The difficulty of writing good forecasting questions

It’s hard to write these questions because you have to sort of think, “Okay, what could the range of outcomes be?” And the outbreak was moving so quickly and we were finding more bad things happening. And so I think that it comes down to the fact that one limitation of these platforms is being able to write a good question. And it’s very, very difficult to do that. And also, the other thing is that when you actually score it at the end, you need to have a clear outcome, right?

Because otherwise your forecasters are really upset that maybe it seemed like you were making an arbitrary choice. Or they’re like, “Well, I am going to argue it’s actually this answer”. And so you need a clear piece of information about what the actual resolution is. And that depends on surveillance and the timing of the surveillance. And if you say, “How many cases will be by X date”, but the situation reports comes out three days later, when you fall in the crack between your two outcomes, then what do you do?

If you say, “How many counties will see cases of measles in this month”? Well, did the person with measles drive through that county? Does that count? Was the person diagnosed in one county and then went back home to another county? How are we counting that?

Deaths are not the only health impact of importance

One thing that I’ve been worried about in this response is it seems like when we think about models of COVID deaths and we think about what we’re doing to stay inside to prevent COVID deaths, from a public health perspective, COVID deaths aren’t the only deaths that occur in the US. They’re not the only public health problem that we’re going to have. And so I’m worried about COVID deaths, but I’m also worried about all these cancer surgeries that aren’t happening because we don’t have elective surgeries, you know, that biopsy that didn’t happen. Someone who should have gone to the hospital for a stroke but didn’t feel like they should. All these things. Growing obesity… I do think that these problems that are coming out of the measures that we are taking to prevent the spread of the transmission of COVID… I worry about them. Plenty of people die from being poor. I worry about suicides. We need to think of this from a big-picture perspective and not just do everything we can just to prevent COVID deaths.

Policy change for future pandemics

The fact that “Stay-at-home orders” are actually possible in the US and seem to work… I had not really had a lot of faith in that before and I feel like I’ve been surprised. But I don’t want “Stay-at-home orders” to be the way we deal with pandemics in the future. Like great, it worked, but I don’t want to do this again. And so I think that it has shown us that we need to probably prioritize some other responses, you know, vaccine development, countermeasure development, increasing the capacity of our healthcare system. Because in the US the healthcare system is either profit or nonprofit but, you know, very slim margin kind of operation. You know, it’s hard to have that extra capacity that’s really necessary for something like this. And so that’s really critical.

Emerging Technologies with Potential to Reduce Global Catastrophic Biological Risks

The ones that I think I’m most excited about in the context of this experience with this pandemic is really the easy-to-use ventilators and microfluidic devices because they can sort of solve our problems or at least help solve those problems with rapid and expansive testing. And then also that if hospital capacity is the thing that we’re really worried about not having enough of, then one of those steps is having enough ventilators and having them be something that you don’t have to have specialized training to actually operate.

One type of microfluidic device would be paper-based testing. It’s just a way to do rapid tests that don’t have to go to a lab and that you can get the results pretty quickly. And so I think this could really change the game. Because right now, if it takes a couple of days to get your test and then it takes a couple of days to get your test back, and by the time you get that and you start doing contact tracing, you’re already in big trouble. It’s hard to really make a change in the epi curve that way. But if you can say, “I’m starting to feel sick”, and then you take a test and you know immediately, you can tell everyone you’ve been in contact in the last couple of days that, “Hey, you know, you should watch for symptoms or take your own test”. I think that’s a game changer.

Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

Tara’s recently published work on misinformation

- Article: Misinformation and the US Ebola communication crisis: analyzing the veracity and content of social media messages related to a fear-inducing infectious disease outbreak

- Blog: The challenge of misinformation during disease outbreaks

Center for Health Security publications

- All of Tara’s publications

- Technologies to Address Global Catastrophic Biological Risks (2018)

- Public Health Principles for a Phased Reopening During COVID-19: Guidance for Governors (2020)

- A National Plan to Enable Comprehensive COVID-19 Case Finding and Contact Tracing in the US by Crystal Watson, Anita Cicero, James Blumenstock, and Michael Fraser. (2020)

- The disease prediction policy dashboard from Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security

- Serology-based tests for COVID-19

- CHS first working definition of Global Catastrophic Biological Risks

- Subscribe to Center for Health Security E-Newsletters

Everything else

- Weaponized Health Communication: Twitter Bots and Russian Trolls Amplify the Vaccine Debate by Broniatowski et al (2018)

- ‘There Are Sensible Voices That Are Emerging,’ How Scientists Are Using Social Media to Counter Coronavirus Misinformation by Jasmine Aguilera

- PM Lee Hsien Loong on the COVID-19 situation in Singapore on 8 February 2020

- Misinformation During a Pandemic by Leonardo Bursztyn, Aakaash Rao, Christopher Roth, David Yanagizawa-Drott (2020)

- National coronavirus response: A road map to reopening by Scott Gottlieb, Caitlin Rivers, Mark B. McClellan, Lauren Silvis, and Crystal Watson (2020)

- Helen Branswell’s articles for STAT

- Biosecurity and Pandemic Preparedness work at Open Philanthropy

- Hypermind prediction market

Transcript

Robert Wiblin: Hi listeners, this is the 80,000 Hours Podcast, where each week we have an unusually in-depth conversation about one of the world’s most pressing problems and how you can use your career to solve it. I’m Rob Wiblin, Director of Research at 80,000 Hours.

The Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security is one of the top global institutions working to prevent health disasters by shaping the development of both technology and government policy.

As you’d expect they’ve been working their ass off on COVID-19, but have also been preparing for this moment for over 20 years.

So I was excited to interview Tara Kirk Sell, who did her thesis on misinformation during disease outbreaks and has worked at the Center for over a decade since completing a very successful career in the US national swimming team.

If you’re as keen on the Center’s work as I am, you’ll be glad to know that as of a few weeks ago you can donate directly to the Center for Health Security through the website for the Effective Altruism Funds, which plenty of you are already signed up to.

They also recently added the option to give to the Biosecurity Program at the Nuclear Threat Initiative in Washington DC.

The Effective Altruism Funds system also supports donations to their four expert-advised funds, and direct donations to 28 other organisations that might be popular donation targets for listeners.

Three projects on the list have been featured on the previous episodes: the Alliance To Feed The Earth In Disasters, also known as ALLFED, the Wild Animal Initiative, and GiveWell.

The site is operated by our fiscal sponsor, the Centre for Effective Altruism, and note two of the expert-advised funds have made grants to 80,000 Hours before.

Alright, at the end of the show I’ll have a few random book recommendations for you, so if you’ve enjoyed my past suggestion for things to read and listen to, stick around for that.

Without further ado, here’s Dr Tara Kirk Sell.

Table of Contents

- 1 The interview begins [00:01:43]

- 2 Misinformation [00:05:07]

- 3 Who has done well during COVID-19? [00:22:19]

- 4 Guidance for governors on reopening [00:34:05]

- 5 Collective Intelligence for Disease Prediction project [00:45:35]

- 6 What else is CHS trying to do to address the pandemic? [00:59:51]

- 7 Deaths are not the only health impact of importance [01:05:33]

- 8 Policy change for future pandemics [01:10:57]

- 9 Emerging technologies with potential to reduce global catastrophic biological risks [01:22:37]

- 10 Careers [01:38:52]

- 11 Good news about COVID-19 [01:44:23]

- 12 Rob’s outro [01:51:02]

The interview begins [00:01:43]

Robert Wiblin: Today I’m speaking with Tara Kirk Sell. Tara completed her PhD in public policy responses to emerging epidemics at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. She is now a senior scholar and assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security where her work focuses on public health policy in response to large scale health events such as disease outbreaks, bioterrorism, or natural disasters. The Center for Health Security might well be familiar to listeners as it received a major grant from Open Philanthropy in part to expand its work on global catastrophic biological risks, which we discussed with the Center’s director Tom Inglesby back in episode 27. Among other things, Tara has studied communication in Ebola and Zika outbreaks and is a co-principal investigator for the Center’s disease prediction project, an online platform to collect forecasts about disease outbreaks and test their accuracy. She contributed to Public Health Principles for a Phased Reopening During COVID-19: Guidance for Governors, which came out just last week. She also happens to have won a silver medal at the Olympics, swimming in the women’s 4×100 metres medley relay. And most impressive of all, back in 2008, she was a contributor for episode 18 season six of the US version of “What Not to Wear”. Thanks so much for coming on the podcast, Tara.

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, it’s such a pleasure to be here. Thank you for having me.

Robert Wiblin: We were going to speak last month at EA Global San Francisco, but then suddenly, somehow that got canceled, I guess along with every other conference in the world. I’m glad we can now finally have a chat about the thing that caused our previous interview to get canceled. But first, our usual opening question is what are you doing and why do you think it’s very important work? I guess I might be able to guess what you’re working on at the moment, but it’d be interesting to hear more!

Tara Kirk Sell: Yes, it’s definitely COVID-19 all the time. I guess I should start out and say that the Center for Health Security has really been following COVID-19 since the very beginning of the outbreak. I’ve been working on pandemic preparedness for about a decade. And so it’s really crazy to me to think, “Hey, this issue that we sort of worked on and thought about as the future is now here and something we have to deal with now today and that everyone’s talking about it. Everyone has an opinion. My parents have an opinion they like to tell me all about”. And so it’s strange, but I think working on these pandemic issues has now shown to be incredibly important and affects our everyday lives. And hopefully that work will help us get through this or at least help us get ready for next time.

Robert Wiblin: What are your parents’ policy suggestions?

Tara Kirk Sell: Well, at first it was really funny because they’re older and I kept saying, “Really, you should stop going out. Stop going to the fabric store. Stop going to get groceries twice a day”. And they were very resistant and now they’re completely flip-flopped and they don’t think that anything should reopen for a really long time. I’m glad that they’re taking it seriously now. So that’s good.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, I think I had a similar experience where my mom’s initial reaction was, “Oh, just let it go through. It’s going to be too much trouble to try to stop it”. But I think she’s changed her mind since then. Is CHS just doing anything that’s non-COVID related now, or has it just kind of eaten up the whole organization at least for the next few months?

Tara Kirk Sell: COVID-19 has really taken over everyone’s lives right now. I think we’ve been trying to keep up our work on a couple other things, but it’s hard even to just read our emails at this point. So I have a couple of projects. My misinformation project that I was doing for Ebola has been published now, and so we were kind of shifting that over to COVID, but at least we were able to finish that out. So a few things that aren’t COVID related, but not that many.

Misinformation [00:05:07]

Robert Wiblin: Alright, well speaking of COVID, let’s start by talking about misinformation which has been, I think, one of your main research interests. If I remember correctly, your PhD was about media and policy interactions during Ebola outbreaks in Africa?

Tara Kirk Sell: Mm-hmm, yep.

Robert Wiblin: What has surprised you about the nature or the extent of misinformation that’s going around about COVID-19. Is it kind of more or less than you’d think, or is it about what you would have predicted?

Tara Kirk Sell: So misinformation is something that we see all the time and we’ve also seen these disinformation campaigns that have really started to move into public health. There was a paper in AJPH about Russian trolls and the vaccine debate. So I’m not surprised that we’ve seen this level of misinformation and disinformation in this outbreak. I’m glad that people are paying more attention to it. I think it is a huge opportunity to sow division in the American public and lead to a lot of lack of trust which to me is really concerning. So I think the themes we saw for the Ebola outbreak, we see those exact same things now. You could almost just take the disease name out and replace it and you see many of those same themes. So that wasn’t surprising. But the extent to which we’re seeing it, I guess, is something that’s new and interesting.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So you mentioned kind of active disinformation campaigns. I’m curious, what misinformation about diseases? Where does it typically come from? Actors who are trying to sow discord who’re coming up with clever disinformation to spread? Or is it just people who don’t have a clue about medicine who say stupid things?

Tara Kirk Sell: I think it’s both. I mean misinformation is when you talk about something that’s not supported by the evidence that causes people to have the wrong belief. But it might just be a mistake, right? Or the wrong interpretation. Disinformation is more purposeful and that is definitely happening. I don’t want anyone to be uncertain about that. Those things are definitely happening. And this is an opportunity for foreign actors to really cause problems in the US.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, how do you measure the scale of disinformation and is it possible to tell, I guess, Russia would be an obvious candidate to be doing that, but are there others as well?

Tara Kirk Sell: I mean, I don’t want to point fingers without evidence, but I think that there are countries that have sophisticated abilities to do this type of thing. And so I think that it’s more than just Russia. Oh, you asked how to measure. Do you want me to talk about that?

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, how do you track it?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, so we tracked misinformation and we didn’t differentiate between disinformation in that case. But we tracked that in tweets about Ebola. And we found that about 10% of tweets had either misinformation or were misinterpretations of true information. And so 10%: is it high, is it low? I don’t know. If 10% of tweets out there are basically false, then maybe that’s a problem. But it’s not like taking over the communication landscape.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I kind of wished that only 10% of tweets were false. Probably more than 10% are not that good. My amateur impression is that there’s like, I suppose I don’t live in the US, but at least in the UK it seems like most people are on board with the lockdown. Most people think that COVID-19 is a serious problem. I guess I wonder how many practical challenges has this misinformation or disinformation actually created so far and might we expect it to get worse as people get more sick of being confined to their homes and open to alternative narratives?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, I do think that it’s going to get a lot worse. I think that in the US we’re currently at risk of losing about half the population. The trust of half the population and the belief that these public health interventions are actually worthwhile. I mean, misinformation, the thing that it does is that it makes you lose trust in authorities and you’re not as willing to comply with some of these public health interventions that you don’t really like. And so I think that there’s a moving narrative now that this isn’t worth it. And so I am worried about the rhetoric that’s emerging and I think it’s going to be a really tough couple of weeks coming up.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. To what extent do you think people are mistrustful of authorities because they have actually just been wrong or slow to respond to this? I suppose it’s like, “Oh, authorities have changed their mind on masks. It seems like for a while they were saying, Oh, there’s not going to be a big problem, but then it turned out to be much worse”. And so maybe people are kind of reacting saying, “Well actually, perhaps the federal government or some of these agencies really aren’t that trustworthy”.

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah. So I teach a risk communication class and I’ll be honest, the federal government has broken pretty much every rule when it comes to risk communication. So they were slow, sometimes not credible, changing their minds, not consistent. All the things that you kind of hope that public communicators don’t do was done in this outbreak. And so I think that people have lost a lot of trust. But I think the thing that’s really important is that we’re all in this together. So if half the people don’t really believe what’s going on, that’s a big problem. It’s not just, you know, “Oh, then you can do whatever you want over there”. I think that it’s something that we should all care about.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I saw some, I think, when you were studying Ebola, I saw some statistic that said 25% of people in the DRC think that Ebola isn’t a real disease. How big a problem is that for trying to control a pandemic over there? Can that show us how big a problem it might be over here if people are not bought into it?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, it’s a huge problem. So if you think, “Okay, we have the perfect countermeasure. Or the right vaccine, the right treatment: we have the exact thing that we know exactly what people need to do and they just need to do it. And if you can’t communicate, and you can’t get people to trust you that what you’re talking about is actually real and what you’re trying to tell them to do is actually useful, you might as well not have anything at all. It’s not worth it. So that’s such a critical component: that trust and that communication.

Robert Wiblin: Well, what about the people who don’t think that Ebola is a real thing? I mean, have they not seen anyone have the disease? It seems like it’s quite a noticeable disease. It seems like it’d be hard to deny that it exists.

Tara Kirk Sell: Right? It might be noticeable, but they might attribute it to other causes. There’s all these conspiracy theories that happen in every outbreak. So I don’t know what specifically was happening there if they didn’t see it. But in the US you’re stuck in your house, or other parts of the world for COVID-19 you’re stuck in your house. You might not see anyone getting it. And so it seems very distant.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Okay. You mentioned that some of the US authorities haven’t really been following best practice in terms of communicating about COVID-19. It seems like it’s a very hard challenge to communicate well to the public who’s a very diverse group, especially when you have lots of active groups out there trying to spread disinformation and trying to take advantage of any mistakes that you make. What can organizations do to protect themselves and do a good job in such an environment which seems pretty messed up?

Tara Kirk Sell: Right, it’s always tough. Especially when you say, “Okay, you have to communicate quickly and you have to also be right and sometimes that’s really hard to do together. So the other thing you can do is say, “Here’s what we don’t know. Here’s what we’re doing to find out that information, and here’s how our plans might change if we found that information out”. But I think the critical thing here is to be transparent and not try to spin anything because I think people are smart enough to realize when you’re spinning them. And so I never would recommend trying to cover anything up when it comes to communication.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. What kind of spinning are you talking about? Are you thinking about trying to explain that things are better than they actually are, or trying to pretend that you know things that you don’t?

Tara Kirk Sell: I think it’s trying to pretend that things are better than they are or being over-reassuring. That just down the road ends up biting you because you know the truth comes out and then it is worse than you said or whatever, and I think that then people lose trust. They don’t want to listen to you anymore.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. That seemed to be an issue early on. Well back in January, it seemed like the mainstream line among experts was, “Don’t worry about it. Not that many people have it. More people die of all of these other things”. Which seemed really misleading to me because obviously the concern wasn’t that lots of people were dying of the disease in late January, it was that many more people would get it in future and so saying, “Oh, don’t worry, don’t panic”, just seemed like it was completely missing the point. And then of course it was setting them up to have to do this 180 a month or two later when it became much more common. Did you also think that it was a bit odd that people were trying to play it down so much early on?

Tara Kirk Sell: Oh yeah. I was really concerned about trust, early early back in February when people were playing it down. How could anyone imagine that you’ve got it all over China and showing up in Europe, that it wouldn’t come to the US. That it wouldn’t spread all over the world. That’s just common sense. I mean no travel ban is really going to be able to actually prevent that. It was in the US already very early on. And so the idea that you didn’t have to pay attention to it and that it wouldn’t actually spread seems to me crazy.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So it seems like it wasn’t only… You might understand politicians who don’t know very much about diseases, who are trying to just put a positive spin on things because that’s the instinct that many politicians have, perhaps. But it seemed like it was people who are more informed like epidemiologists. People who do actually understand diseases or medicine, who people were turning to for advice and they were saying, “Don’t worry about it”. What was going on in their minds? Why did they think this was a good move?

Tara Kirk Sell: I don’t know. I’m not as familiar with everyone who was saying, “Don’t worry about it”. But I was in my little cocoon of people at the Center who thought this was a big deal. So I don’t know what was happening honestly. I do think though that there were people saying we shouldn’t panic and I certainly think that that is the correct message. That we should be thoughtful about how we move forward and that we need to collect this information so we can make the right moves. I don’t think that was a problem but yeah, I guess I wasn’t that familiar with many people who were saying, “Don’t worry about this at all” other than politicians.

Robert Wiblin: I think part of what was going on was perhaps people wanted to promote this idea of “Don’t panic” because they were worried that the public would panic and they felt that the way to do that was really to talk down the risk a lot and then it kind of got a bit out of control, but I’m not sure how big the risk of… It seems like what’s ended up happening is much worse than the public panicking in January. Or maybe I just haven’t seen what happens when the public really panics. I guess people panicked later and it wasn’t that bad.

Tara Kirk Sell: Well, in the academic world, we try not to say that people will panic because people are acting in ways that are rational considering the information that they have most often, at least. I mean a few times you can have instances of people not acting rationally. But for the most part, if there are information voids or there’s the sense that things are getting out of control, then people will act in more intense ways. And so that’s what happened because people were over-reassured and then had this smack them in the face.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. You mentioned earlier that one way for authorities to protect their credibility is to admit what they don’t know. But I suppose there’s kind of a difficult trade off there. Because I suppose admitting what you don’t know, maybe that makes some people trust you more because they’re like, “Oh, they’re being sincere about what they don’t know” and it makes it easier to then change it. To say something different later on because they can then say, “Well, we previously didn’t know and now we do”, and you’re not doing a backflip. But I suppose saying that you just don’t know lots of things might create this world where people then start looking for alternative authorities because they’re saying, “Well, if the CDC doesn’t know all of these things, that’s not very satisfying to me. I have to find someone else who’s going to give me answers”. Maybe false answers. But yeah, is there a difficult line to tread there? Conceding what you don’t know versus saying nothing?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah. I think it is difficult for anyone. But I think what you could say is, “Here’s what we think right now, but there’s a lot of uncertainty about it and here’s what we’re doing to sort of reduce that uncertainty and so the answers may change”. I think a lot of it is just framing and sort of admitting that maybe you’re not an expert or you don’t have that level of understanding. I think that’s fine personally, but that’s just my opinion.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, are there any countries that have done a good job? Misinformation or communication wise?

Tara Kirk Sell: I was really impressed with the Prime Minister of Singapore’s messages that he put out. They were video messages, and they were incredible when it comes to risk communication. They were explaining everything I’ve said here on what you should do in risk communication, and did a great job of foreshadowing how they might change things coming forward. So I was incredibly impressed by that.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Maybe we’ll stick up some links to those videos. Sometimes when I was feeling anxious about the situation, I would go back to YouTube and re-watch some of the videos of him explaining things and be like, “Yes, a source of common sense and like calmness in the eye of the storm”: put it on my mental health rotation. What should we think about misinformation that comes from government? Is that something that we should understand in the same way we do with other misinformation, or is that something that needs to kind of be studied within a different framework?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, misinformation can come from governments. I’m not gonna try to cover that one up. It certainly can happen. I think that it’s possible that people can sort of make mistakes, or that information can change over time. But it can come from companies, people, governments, whatever. It can come from a variety of sources.

Robert Wiblin: Do you have any view on what the internet companies should do? I noticed that YouTube and Facebook and actually so many sites now, they’ve got these banners at the top where they’re trying to direct people towards authorities on coronavirus, which here I guess is the public health people in the UK. I suppose over there they’re linking maybe to the CDC. Is that a good step or do you think that people who kind of reject the mainstream narrative are just going to reject those popups as well?

Tara Kirk Sell: Well I do think that those efforts are really valuable, and the changes to the algorithms that they’ve made can make a big difference. But I agree that if you’re someone who rejects mainstream science or the authorities, then that’s not going to be helpful to you. And so I think this is where research comes in and trying to understand the best ways to access these populations who are distrustful of authority. I think that the answer to the problem of misinformation isn’t necessarily that the tech companies should solve it all for us. I certainly don’t want Facebook to determine for me what’s true or not. And so I think that there’s a lot of stakeholders and I think members of the public also have to take a hard look in the mirror and understand and figure out how we’re figuring out what information sources to trust. And I think that there’s a whole lot of stakeholders who need to think about it.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Have you seen this paper about… It’s a little bit dark, but it’s, I guess, different mortality rates from COVID-19 in different districts of the US depending on whether they watch Tucker Carlson, the Fox News host, more than they watch Sean Hannity?

Tara Kirk Sell: I saw the abstract to that. I mean, I think it probably has to do with how quickly you were interested in social distancing. Although it could also have to do with the demographics of how old you are and if you’re able to social distance. I don’t know the demographics of those two shows.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Just for listeners, they looked at different counties, I think, in the US seeing whether people who watched the Fox News host, Sean Hannity or Tucker Carlson more. Tucker Carlson spent most of February saying that COVID-19 was going to be a massive problem. Sean Hannity spent most of February saying that it wasn’t going to be a problem at all and they noticed that places where people watch Sean Hannity more, the fatality rates were higher, or more people had died of the disease. I suppose I’ve seen enough empirical social science to wonder how good are the methods there? If you went past the abstract, would it really hold up? If it’s correct, it’s kind of startling. Do you think Sean Hannity… in a sense, people will have died. His viewers will have died potentially because he got this wrong. And I wonder how much people will feel that sense of responsibility in the media to get things correct.

Tara Kirk Sell: I think the media should feel a responsibility to get things correct. But in this case I don’t think that that was right and I think it was pretty bad.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, how can people figure out who to trust? Especially if they want to just go beyond highly confirmed facts that the CDC is putting out and they want to stay abreast of the cutting-edge science in it. Yeah. What are indications that are hard to fake that something is actually credible?

Tara Kirk Sell: So it’s hard because if you’re looking at preprints, you have to have an understanding of how those methodologies work. And if you’re not in that field, it’s hard. I’m in public health, but I don’t know how to parse exactly what to be worried about in particular in a modeling study. So I think trusted mediators are definitely important there. There can be some leading journalists who seem to have really gotten things right but also, you know, I don’t want to plug our stuff too much, but I don’t have anything to do with the CHS COVID newsletter, but I think it is excellent. I get a lot of information from that and try to follow a couple other news sources. But I’m also just run over with so much information. I think that’s a huge problem that’s happening for everyone right now is that there’s just too much to absorb. I think it’s called data deluge. I just have a hard time even keeping up with my emails. So I try to get what I can as the world’s moving at lightning speed.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I had that experience in late January/early February. I felt like I could keep up with what was being learned about COVID-19 and then just in March things snowballed so quickly. I wasn’t even able to keep up with the articles that people were literally emailing me rather than just randomly start reading through them. It’s just like, “I give up. I can’t keep track of this. I’m just going to stop trying to be at the cutting-edge and just learn things a month late and that’s going to be fine”. Maybe that’s a sensible approach because there’s so much going on that really all you can do is specialize in some narrow area and really understand that. And a lot of the rest of it just kind of has to pass you by.

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, I do think some things you’re just going to have to say, “I’m going to delete that from my inbox”. But I think one thing that can be really interesting now is that there is more information coming out about what’s happening in localities and what’s happening on the ground. So my colleague Amesh Adalja, he’s a clinician, he also works at CHS and so I really value his perspective because it’s first-person. And I think the more that we’re able to understand sort of what’s happening in localities based on the information that’s coming out of them, I think we’ll have a better picture of what’s happening rather than these large countrywide models or whatever that I think don’t have enough granularity to really tell us that much.

Who has done well during COVID-19? [00:22:19]

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I’ll just plug Scott Gottlieb who contributed to a paper that came out last week about what governors should do and Helen Branswell who’s a journalist at Stat News — actually Stat News as a whole has been pretty impressive, I think, in covering this. I guess it’s kind of an industry magazine for pharmaceutical companies or for the medical industry, and I guess it really does help when journalists have some expertise within the domain of which they’re writing, which is not always the case. But it means that I think they’ve been able to cover stuff that other places have not been able to make sense of.

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, she has been great. And then Scott also has a very sensible voice, so I’m glad that he’s been publishing and pushing things out.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Are there any institutions in the US that have overperformed how well they thought that they would go and perhaps should they be given more authority to play a big role in future pandemics?

Tara Kirk Sell: I was really impressed with the King County public health department. They were the first to recognize that. I thought they were really on their game. I thought they were approaching some very sensible solutions. Trying to think through things with the understanding of local conditions. So I was very impressed with them. I think that some states have also done a very good job. I think that when we talk about risk communication, I think the risk communication from Governor Cuomo has been excellent. And I also think that Governor Hogan in Maryland, where I live, he was on his game very quick. And I do think that the states have shown leadership, whereas we had some disappointing efforts by the federal government.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Do you think more power to respond to pandemics should be devolved down to the state level or, I suppose, I don’t know, more local levels in other countries as well? Or does that just create other problems?

Tara Kirk Sell: Well, in the United States it varies based on Home Rule vs. Dillon’s Rule. Who has the power? Is it to the locals or is it to the state? I do think the states have done a good job and that the more local you can get, the more responsive you can be. But that spreads out response resources. And in some cases now, we have states actually banding together to put their resources together. In an ideal world, I think the CDC would be empowered to do the great work that we know that they’ve been capable of in the past. Right now they’ve been a little bit silenced and I think that it’s important to have a really strong federal public health agency. So kind of a middle of the road answer there.t.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I guess I’ve heard a lot of respect for the CDC in the past, but most people seem to have been disappointed with their response to this one. Did they not have the right people or was it political interference in the CDC that made it hard to do their job?

Tara Kirk Sell: I feel the same and I don’t really know exactly what has happened. I used to work with a lot of people there and I still work with some of them. Over the past few years, many people have retired: some people who I think had a lot of institutional knowledge and a lot of capability to manage a pandemic. So I think that there has been a loss there. I don’t know exactly what happened and I don’t know if we’ll ever know. But certainly, the efforts with regard to testing were pretty disappointing.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Speaking of testing, do you have any view on the FDA and their performance? I’ve seen a lot of people who’ve been kind of angry with them for seemingly holding up advances in testing or in other medical equipment that maybe we would like to roll out with a lower level of testing or confirmation of how well it works and safety testing and so on because this is an emergency situation.

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, I’ve seen that criticism as well. I think that criticism is reasonable. I don’t get too involved in what’s going on at the FDA. To me it’s sort of a black box going on there.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Interesting. There’s been some disappointing things in the US, but if you look at the number of deaths across the country as a whole. The amount of contagion across the country as a whole, it actually doesn’t seem to have done that much worse than many other countries. At least on a per capita basis. It hasn’t done well, but it’s not as if we can say, “Oh, this is all the US federal government’s fault”. It’s like, other countries have often done similarly badly despite not having whatever the unique issues are with the United States. And so it seems to me like around the world, governments have been pretty slow to react to this, potentially being weeks behind where they could have been if they were very proactive. And I wonder what’s the reason that governments tend to lag in their response? Why aren’t they running ahead of it? I suppose one thing is you have this exponential growth where in order to get ahead of where the virus is, you have to suddenly 10X your response one week to the next, because it’s amping up so fast and maybe bureaucracy is not designed to do that or people just don’t want to believe that things are going to be so bad. But it seems like there’s potentially quite deep-seated factors that cause things to happen too slow?

Tara Kirk Sell: I think there’s a number of things happening here. One is that the reluctance to admit that something really bad is coming down the road. I think the other is that taking action has its own cost. If we had started saying “We’re going to close all businesses and do all these things” without our testing actually in place, and we had very few cases, I think it would have been hard to justify that even though we know that there were cases all over, we just weren’t testing very well. So it’s a mix of things and certainly it was a difficult situation, but I think that it would have been better to have testing set up earlier so we knew what was going on earlier. We’re not trying to sort of pop in in the middle of an epidemic curve and try to figure out where we are. I think that would’ve made a big difference, and so I think that was part of the slow reaction. But I think another part was just reluctance to sort of do the things that were hard.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, I guess there’s this interesting paradox that I suppose closing down the economy, it’s very hard to get broad-based support for that until more people have died. Until things are going worse. But of course by the time that’s happening, now you have to close down the economy for much longer to bring down the case numbers sufficiently. I suppose you can see the example of other countries going really badly, like in a peculiar sense, Italy was very helpful for the rest of the world because seeing the carnage there really prompted other people to say, “Oh my God, we’re going to be that in two or three weeks”.

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah. So when Italy happened, I said, “Whoa, this is actually in a country that has advanced medical care and can’t handle this”. And we knew that it was going to be bad, but Italy really showed how the case fatality rate changed when you didn’t have appropriate medical care and you had an older population. And so I think Italy was a big wake up call to say this isn’t just less than 1% case fatality. This could be bad if you’re not able to actually handle it with your health system. And that was sort of the wake up call I think for everyone.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. There’s this funny thing that… I’m originally from Australia and Australia has actually done this quite well. It seems like they imposed lockdown sufficiently earlier. They’ve managed to bring new case numbers down to really low levels already. But then it means that I’m hearing from people that people are losing support for the lockdown, or losing interest in it because not enough people they know have died. So it’s slightly hard to maintain interest in it because they have been so successful at stopping it. I suppose it’s slightly nice that I suppose Sweden, or there’s some countries that are pursuing a slightly heterodox approach where they’re potentially not going to have “Stay-at-home orders” and so we might see some more spread. Perhaps that will be an example to the rest of the world depending on how it goes. Showing like, “Well this is what would have happened”.

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah. So I think everyone’s tired of being in their house. I’m tired of being in my house. I think it’s going to be very difficult to keep up this communication and ask people to keep doing these things that they just don’t want to do anymore and that they’re not seeing cases in people they know. And so I think that’s going to be difficult. I don’t know if people have to learn the hard way or if there are ways that we can sort of meet in the middle. I hope that that’s the case. It certainly seems like these really thoughtful approaches that public health has sort of put forward as what the gating criteria for moving forward for many states are not going to be met, and people are just gonna do it anyways.

Robert Wiblin: Interesting. I suppose the point of the lockdown was to bring down case numbers. Also to give us time to put in place ways of dealing with a renewed outbreak, like testing capacity or more hospital capacity. Do you think that time has been used well given how expensive it was to buy each day of delay?

Tara Kirk Sell: Absolutely not.

Robert Wiblin: Go on, this sounds good! Well, it sounds terrible…

Tara Kirk Sell: That is a problem with the thing that has been, I guess, most infuriating actually about this outbreak. That we knew it was happening in China in January and nothing was done to really actually make measurable changes on the ground in the US to get ready for it. And then we had it happen in the US, and we all went into lockdown, as you said, at immense cost. Incredible cost to ourselves right now, and to our kids in the future. I mean, this is going to be a big problem for a long time and still, for us, six weeks go by and I don’t see huge improvements in testing capacity in the serology, in PPE, in hospital capacity. These things just haven’t happened and I was sort of wishing that we could have timelines where we say, “This is what we’re going to do by this date and here’s the person responsible and we’re going to take names until we get it done”. I would have liked to see a little bit more urgency in saying each day is many livelihoods. And each day is critical that we push our opening forward one day in a responsible way. And I just don’t think that has happened.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. What do you think has been stopping it? I suppose I feel sympathetic to the people trying to do this response really quickly because they may just not have very much experience in the area. And I suppose lots of different groups are competing to get protective equipment and maybe the factory is already maxed out and there’s only just so much that the world can do. But it sounds like you think that we’ve underperformed what is realistically possible?

Tara Kirk Sell: You know, I think this is a hard problem and I have sympathy for that. But at the same time, so is how many millions of people we have unemployed. That’s a big problem we have. We have many, many hard problems that we’re dealing with here. And so I just think, you know, we went to the moon, we built a nuclear bomb. That’s a hard problem, you know?

Robert Wiblin: Can’t we make some masks?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, exactly!

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, so are there any specific suggestions of stuff that you think should have been funded maybe that wasn’t funded or maybe regulations that should have been loosened to make things go more smoothly that weren’t loosened?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah. So with my public health hat on, I have to say local public health should be funded. The funding for the PHEP program, the Public Health Emergency Preparedness program has really declined in the past decade. Same with the Hospital Preparedness Program. These funding lines are critical and they’ve really lost a lot. So that’s one thing. The other thing is investing in technologies. And I think that we do need to be able to think outside the box and move a number of different technologies forward. I think this is something that the EA community can really help everyone get their arms around what kind of new things that we should be looking at. How do we change the game?

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, it’s interesting. I suppose I’m very optimistic about how things are going to go in Australia because they managed to bring down the case numbers to a pretty low level, and in the meantime, their testing capacity has gone up quite a bit. So now the number of tests they can run per number of cases that they expect, at least over the next few months, is pretty good such that they can do a lot of testing and tracing and probably keep it under control for quite a while. Is it realistic that other countries could have done this as well if they’d had, I suppose, similar capability to expand their ability to respond whenever the “Stay-at-home orders” end?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, so I mean it looks like South Korea has done a really excellent job. They do a great job contact tracing and they’ve had incredible levels of testing. They had a trial run with MERS so obviously they were able to test out what they were doing and improve it and change some laws. And so I think that really did make a big difference. I think New Zealand and Iceland have also done good things. But let’s also now think about the fact that three of these countries are island nations with moderate population sizes. So that makes it a little bit different. These countries have done a good job and I think that the US could emulate that a little bit.

Guidance for governors on reopening [00:34:05]

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. All right, let’s move on and talk about the ‘Public Health Principles for a Phased Reopening During COVID-19: Guidance for Governors’ which CHS put out last week. You were one contributor to that report. What was it trying to say and I guess what was its most valuable contribution in your view?

Tara Kirk Sell: So I think this report was really trying to frame different types of business or activities in a framework that was showing what the risks were as far as level of contact. So was it close contact? How many contacts there were. And then also how modifiable those contacts are. And I don’t think that there was really like specific no-go guidance on that. It was more, “Can we provide people with information that they can then take to a larger stakeholder group and have that discussion about what’s worth it”. There are different levels of risks and sometimes you might take something that might be a little bit higher risk or you have a lot more uncertainty about like schools and you might say it’s worth it, but it’s all in a mix. It’s not just public health who should be making this decision. It should be a mix of stakeholders who bring their expertise into the conversation as well.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So I guess I’d been looking for something like this and I hadn’t seen a similar report until this one came out. Maybe there was one out there that I’d missed, but I guess you were kind of trying to rate these different activities, because it seems like we’ve got this whole spectrum, thinking as an economist, there’s activities that create the most disease transmission per util that people derive, which is maybe, I don’t know, a music festival or something where people are in enormously close contact that are probably not super essential that they would do that. And so probably we’re not going to have really crowded music festivals, not going to have a mosh pit for a little while. But then there’s like all the way down to things that we’ve already closed where they’re quite important economically, like people’s livelihoods are being destroyed because they’re not happening.

Robert Wiblin: But the amount of transmission isn’t that great, say, going to a clothes shop that’s not that busy, not that packed. And I guess you’re trying to draw out that spectrum and say, “Well, if you’re gonna open some things, well here’s some things that are more promising”. Either where the number of people you’re close to is not that large, or you don’t spend that long around them. Or you can kind of adapt the shop, say, by saying, “Well, people have got to keep their distance” and then you can reopen the clothing stores. I suppose some of the interesting things are, I guess, shopping malls and retailers seem like they can reopen. I guess parks and actually non-contact sport was one which you’re saying, “Well people could probably play tennis, right”? So we could perhaps be a little bit creative.

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah. So I mean I pushed for that one because as a swimmer, I was like, “There’s not that much mixing that’s going on when we’re swimming at the pool as long as we’re not breathing all over each other at the end of the lane”. I think it’s pretty clear that ventilation plays a really big role here. We’ve had some studies… I saw a preprint just the other day about the different outbreaks that they sort of tracked in China. And for the most part those have really come from household transmission or from transmission in transportation. And so when people are in very brief contact outside, I don’t see that as sort of a huge risk. And at this point it would be ridiculous to think that we’re trying to strive for zero risk, right?

Tara Kirk Sell: No one lives a zero-risk lifestyle. And so I think that we’re just trying to reduce the level of risk of transmission here. So we want to avoid close contact and we want, you know, not to be indoors. And I think that businesses and people can really think through those requirements and make adjustments. And that’s what I think we should really be striving for here is that people can make these decisions based on the knowledge that they have about the disease rather than these overall orders that sort of compel them to do something.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Are you seeing a lot of people responding? I guess I’ve seen a lot of businesses and offices thinking about “How can we reopen”? Because they want to reopen desperately. So they’re thinking, “How can we reopen the office in a way that isn’t going to get our employees killed”? Maybe even in some ways the government response has been a bit disappointing, but perhaps we could see quite a lot of individual responsiveness and flexibility that could allow things to return to some semblance of normality without the disease breaking out again.

Tara Kirk Sell: Right. I do think that businesses have been very flexible and are trying to push for ways that they can do things safely. And I think that’s really great. You mentioned going back to the office. I personally think that probably if you’re able to work from home, that’s one thing that I would say you should probably keep doing if you can do that effectively.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, I guess maybe in person things construction, perhaps. It’s like warehouses, factories and all that. Also try to figure out how they can keep running. So you said we don’t have much evidence of people catching it from strangers passing by them on the street or in parks or anything like that. It’s mostly in the house, you’re saying, and public transport which are the two key factors. It makes me wonder then–

Tara Kirk Sell: Well that’s from the preprint.

Robert Wiblin: Okay, right. Well let’s just take that as gospel. That makes me wonder… I’ve heard some people who’ve been a bit skeptical about the lockdown because they say, “Well, you’re going to get so much transmission within the household because people are spending tons of time in close contact with their family and housemates then, that given the enormous cost, maybe it’s not actually going to do as much good as you think”. Do you have any view on that?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, so I mean I think people are already in contact with their household and so I mean, I’m not saying I wouldn’t say that that would be a reason to say no on lockdowns, but I do think… I’m not a fan of, like I said, of the lockdown as a coercive sort of measure. I think that providing guidance and helping people understand what should really be done is much better. The costs are immense though. And having people be thoughtful about their contacts I think is important. But even if the lockdown isn’t happening, I’m still having my kids cough in my face. So I don’t know if that’s a huge difference.

Robert Wiblin: I guess part of the reasoning is that as long as you’re with the same people at the same house every day, they can’t infect you twice. So either you get it or you don’t after a while.

Tara Kirk Sell: Right. Although we were social distancing for like two weeks and somehow we caught a tiny cough. Like my whole family and I just…

Robert Wiblin: I’ve been out in the country in this house for like five weeks, seeing practically nobody, and last week I got a cold. I’m like, “Wow, this is incredible. How is this not enough”? You’d think at least if I’m meeting nobody, at least I wouldn’t get colds. But no, it’s not even the case. Yeah, what’s been the response to the report? You mentioned in the notes that librarians weren’t pleased by the suggestion that maybe libraries are a somewhat safe environment to resume normal life.

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah. So I wasn’t really involved in this debate, although I heard from Caitlin who was the main author of the report that these librarians were saying, “You know, we do have close contact with our customers or with people who are coming into the library”. If you think of it from the perspective of someone who patronizes a library then yeah, maybe you’re not coming in contact. But if you think about a librarian, then they are. I think actually that’s a fair criticism and also something that you could think about for every business. There’s a lot of unique approaches to business and also varying types of contact occurring within those businesses. And so I think an overall judgment can be helpful, but at the end of the day, that’s why we want to have stakeholders involved so that they can articulate those differences and bring them up as important components of a decision-making process.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. It is an interesting point that I suppose even in a clothing store that’s not crowded, for someone just going there to buy something, it’s probably a pretty safe trip. But then someone who’s behind the counter all day constantly being exposed to different customers, maybe the risk really does add up, and who’s going to want to take those jobs?

Tara Kirk Sell: Right. Well, I agree, but I think also unemployment’s pretty high. People need to make their rent. So then it’s sort of a situation where people don’t have a choice.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. There was a section in the report talking about the importance of consulting with lots of people in the community before deciding what things to reopen. I suppose there’s an obvious case for that, which is you want to understand people’s preferences about what to reopen and I guess get buy-in from the people who are gonna actually have to do these things that you’re asking them to do. But as I was reading it, I was thinking it could just be that members of the community, like stakeholders in this decision perhaps, don’t have the expertise to really say what activities are risky and which ones aren’t. And they might pressure a politician or pressure officials to reopen something that’s very important to them, not realizing just how dangerous it is. Is there a case for focusing more on people who have expertise in how dangerous are churches, how dangerous is swimming, rather than people who want to go back to swimming?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah. So I think that that’s a fair question. I would say though that decision makers need to be able to understand that epidemiology and people who want to advocate for themselves should be able to do so. And then if the decision goes against them, if they’ve at least been part of the conversation and had their considerations thought about. So I think it’s not a problem to have people’s voices as part of the conversation.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I suppose as long as the politicians are also paying attention to their public health people. It’s a question of balance and then, yeah, just make sure you don’t listen to only one group.

Tara Kirk Sell: Right.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Are there any things that you’re worried will be open too soon?

Tara Kirk Sell: I mean, yeah, there are things. I don’t think that close contact in bars is probably a good idea. It’s an indoor environment. There are a lot of people very close in bigger crowds. Georgia is opening up soon. I think they’re opening up movie theaters. That seems at first kind of dangerous. But I think that there are ways you could modify it, right? If you had people sitting far apart. The same with the gyms. There’s a worry about transfer via fomites, but I also think that there may be ways to modify the situation so that people are safe and that there are a lot of people who’ve been in their houses and we don’t want to increase odds of all these other chronic diseases that can occur from being very stationary.

Robert Wiblin: I guess, yeah, coming into this I would have thought there will have been lots of studies of where people catch colds or where people catch the flu. Like is it at the gym, is it at the pool, is it the church? Is it somewhere else? But it seems like we haven’t really done those studies. I guess when I then think about it, I think, well the way that you might study that is to create some new disease that’s harmless and then give it to people and then see how it spreads throughout the city and where people caught it. But that may not get past ethics approval. So perhaps this is a slightly harder thing to answer than what I thought. But is this kind of research that we just really need to figure out; where do people get the flu the most?

Tara Kirk Sell: It also varies by disease. So then you’re just not sure. And then it’s expensive and hard to contact trace, especially if you have high levels of flu in the community. You know, how many cases of flu do you have and how many times are you exposed? I think it’s pretty tough. There have been studies to see how long a viable virus can be found on certain surfaces. But I’m not sure that those have included infectious dose or that kind of thing or how it works actually in humidity and sunlight. So we’re getting into an area that I don’t know that much about, but I think that those types of things would be really helpful.

Robert Wiblin: So it sounds like a lot of what we know comes from contact tracing early with diseases where we find, in almost all cases, we can track it to someone living with someone or being on public transport or something like that.

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah. And so there may be a little bit of a bias there because it’s more obvious if you have caught it from your housemate or you know what was going on in public transport. But I think that that’s what I saw in that… I guess I’ll caveat again, in that preprint. And then South Korea has also been keeping track of these things. You know, they had these outbreaks in these churches where there’s close contact. You’re in close contact for a long time. You’re indoors. So I think it’s starting to become more and more clear. There may be risks about spreading the disease in other situations, but that close contact indoors for a long period of time is really the main way that I think people are getting this disease.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I guess that’s actually a little bit hopeful in terms of maybe we can reopen a fair few things without letting R get too far above one. If you need close contact–

Tara Kirk Sell: Right, right. I think we have to be careful, but you know it’s possible.

Collective Intelligence for Disease Prediction project [00:45:35]

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. All right. Let’s move on and talk about some other things that are being done at the Center for Health Security. You’ve been a leader on this Collective Intelligence for Disease Prediction project. What is that and how is it similar or different to other forecasting platforms like Metaculus or the Good Judgment Project?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, so it is actually pretty similar. Crystal Watson and I had started and done a past prediction project where we were actually doing a prediction market. But it’s actually really hard to have people who aren’t really that experienced and have a different sort of infectious disease day job to do commodities trading on an infectious disease outcome and so we switched it to a platform that does a lot of the work for them. And this was different from the other platforms in that it was really just specific to infectious disease; there are other questions on those other platforms that are more general. And so we started that up about a year and a half ago with funding from Open Philanthropy and that was a year long project and we were just about to close down in December, but we got additional funding from Founders Pledge and that led us to keep on operating. So one of the goals at the beginning was to establish this platform and we would have the platform set up and we would have forecasters ready to go in case there was a pandemic and here we were. We had it set up.

Robert Wiblin: It’s lucky you got that in December. COVID was already spreading.

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, exactly. So we were able to field up about a dozen or so more questions about COVID-19. It was actually really interesting because there was a lot of uncertainty. The forecasters didn’t really have a clear answer on some things like “What’s the case fatality rate going to be”. But then in other cases they were very certain. And it sort of shows how hard it is to write these questions because we would put these ranges of cases and immediately forecasters would go to the highest range and then cases were just exploding and it was hard to tell, you know, “Are cases exploding or is our testing capacity exploding”? And so it did give us some new answers there. That this wasn’t just going to increase at a moderate rate that we would be able to go along with. Over time it was going to be explosive.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Interesting. Okay. So just to back up, so you set up this platform where contributors could make forecasts about disease outbreaks and had been running for about a year. How many contributors did you have and did they have a lot of experience in the area?

Tara Kirk Sell: We had various numbers of contributors over time, but we’d over a thousand people who signed up. Each question probably got between 60 and 150 forecasters working on it. And so they had varying degrees of expertise, but a lot of them were in the infectious disease world. We sent out some advertisements through ProMED-mail and so got a lot of attention and interest from around the world. And so that was really something that we wanted. We wanted to have this varying experience. We didn’t want everyone to come from the same viewpoint because we thought that we would have stronger forecasts if we had all these different perspectives. And so that’s how we started out. We had a lot of different questions. We started out with other things like Ebola and cholera in Yemen. But at the end it was really all COVID.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. And this wasn’t a money one or anything like that. I guess, were people doing it for bragging rights or just to be helpful?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, so no, there were prizes. We’re pretty sensitive to how it looks to have people trading on death, basically. I don’t want anyone to ever have that issue. And so there were prizes for people who were the most accurate. But we weren’t doing commodities trading and we just had a prize for one through five and then we had a random draw based on how many points you had for the next 20. And so people were incentivized to do well, but I was hoping to avoid that unsavory look of having people trade on these bad outcomes.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. As an economist, my reaction is like, “What? You don’t think life is precious enough to be worth trading in prediction markets”. But I think that that may not be the typical response that people have to people making money forecasting awful stuff. Okay. So how did they perform?

Tara Kirk Sell: Well for the most part they performed really well. But the thing that we learned is that it’s not like magic, right? People need to have information to make good forecasts and if they don’t, or if the surveillance information is bad or really biased, then they don’t make good forecasts. And so I think it’s great to have these newfangled ways of getting opinions and thinking about the future. But if you don’t do that traditional epidemiological surveillance, you have a hard time. And so I think that it just says that we need to do surveillance pretty well.

Robert Wiblin: I guess. Yeah, it has the shit in shit out problem. That just if there’s no actual base information collection that they can rely on, then their forecasts can’t be that good.

Tara Kirk Sell: Exactly.

Robert Wiblin: It’s interesting. I was following the Metaculus predictions which were running fairly early on and I kept noticing that they just always seemed to be trending in one direction. I guess good forecasts should go up and down roughly equally or it should be hard to predict where they’re going, but it seemed to just constantly be moving upwards, which made me wonder if there was something broken about the algorithm. That it was constantly trailing. It was maybe using old forecasts or it could just be that maybe it was just a surprisingly large outcome. So we just kept learning more and more bad things. Did you find anything that there was… what’s the term for this… It should be a martingale, which I guess means that you can’t predict whether it’s going to go up or down. Did you find that in your methods?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, so actually some of those questions we actually cross-posted between us and Metaculus and they were great in setting something up so we could compare at a later date. I mean it’s hard to write these questions because you have to sort of think, “Okay, what could the range of outcomes be”? And the outbreak was moving so quickly and we were finding more bad things happening. And so I think that it comes down to the fact that one limitation of these platforms is being able to write a good question. That the question requires a really good forecast just from the person who writes it. And so it’s very, very difficult to do that. And also, the other thing is that when you actually score it at the end, you need to have a clear outcome, right?

Tara Kirk Sell: Because otherwise your forecasters are really upset that maybe it seemed like you were making an arbitrary choice. Or they’re like, “Well, I am going to argue it’s actually this answer”. And so you need a clear piece of information about what the actual resolution is. And that depends on surveillance and the timing of the surveillance. And if you say, “How many cases will be by X date”, but the situation reports comes out three days later, when you fall in the crack between your two outcomes, then what do you do? So I mean it’s really hard to write the question.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, that’s interesting. Yeah. That’s something that Philip Tetlock has said when we interviewed him. That he would almost like to spend less time thinking about good forecasting and more time thinking about good question-asking. Did you learn anything specific about how you can do this better, or is it just a perpetual challenge that maybe the thing you really want to know you haven’t got an objective outcome for and you have to keep changing the question because the world keeps changing and so the thing you want to know every week is different?

Tara Kirk Sell: Yeah, I mean that’s true. I think the question writing is the hardest part. The forecasting I think is pretty straightforward. But yeah, writing the question in a way that’s not ambiguous… You know, if you say, “How many counties will see cases of measles in this month”? Well, did the person with measles drive through that county? Does that count? Was the person diagnosed in one county and then went back home to another county? How are we counting that? And so we got better at it as we went along because we avoided some of these pitfalls that we experienced early in the project. But it was still incredibly difficult, even till the end.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. That’s interesting. I suppose when people I know have made bets against one another on predicting things that will happen, very often they’ve decided that there’s no objective way of deciding who will have won. So they just appoint someone who they both like to just decide who was quite closer to the truth. I guess I haven’t seen that many of those bets resolved. Maybe they’ll just end up bickering about whether the arbiter was fair?

Tara Kirk Sell: Are we talking about a Slap Bet Commissioner?

Robert Wiblin: What’s that?

Tara Kirk Sell: A Slap Bet Commissioner? It was from ‘How I Met your Mother’ and they had a bet that the person who won got to slap the other and so they appointed a third party to determine the rules of how it would occur.