Pursuing fame in art and entertainment

Review status

Exploratory career profile

Table of Contents

What is this career?

This exploratory career profile discusses musicians, visual artists, actors and fiction writers, and in particular attempts to become famous within these fields. We have not yet considered other careers in the arts and entertainment, most of which have quite different characteristics, and so our view on these careers should not be generalised from this career profile. We also appreciate being contacted with corrections, relevant data, or further important considerations.

Here we will consider these careers from the perspective of someone early in their career (15-25) who could reasonably aim to be admitted to a selective training school in their artistic field.

Many people believe that progress in the arts has intrinsic value. This may be true, but in this profile we will consider only how much these careers help people – that is, how many people are helped multiplied by how much it improves their lives.

What are some reasons to pursue this career?

- Many people find pursuing a career as an entertainer or artist to be highly meaningful and enjoyable.1

- Outstanding art can entertain and delight millions of people.

- Some of the most famous entertainers become incredibly wealthy, which they could then use for highly effective philanthropy.

- Entertainers who become famous, whether wealthy or not, have the potential to engage in celebrity advocacy on important issues. Bono is an example of this.2 Those who are less famous can also engage in advocacy on a smaller scale.

- Art itself, especially genres which involve encouraging people to imagine themselves in the circumstances of others, may help in the ‘civilizing process’, encouraging people to care more about people who are different from them. 3

What are some downsides of this career?

- Earnings and fame are incredibly unequally distributed because the world’s single best entertainer in any genre can reach almost everyone on Earth. There are a handful of runaway stars like Beyonce or Bono, but the vast majority of people who attempt to enter the entertainment sector achieve little or no recognition. In that case their direct impact, earnings and advocacy potential are likely to remain low unless they change career track.

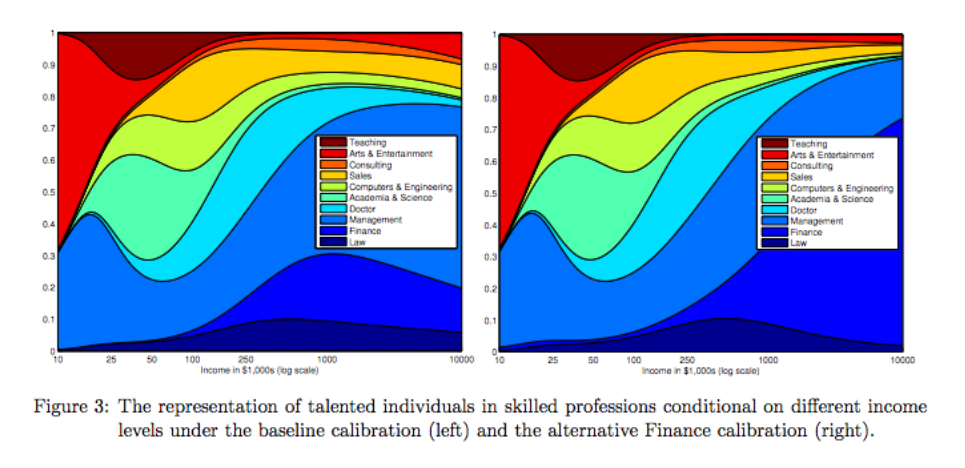

This figure, applying only to Harvard graduates, shows that people in the arts and entertainment are very overrepresented among those with the lowest incomes, and also somewhat over-represented among people with the very highest incomes. (Lockwood, Nathanson and Weyl, 2014) 4

- Because many people would like to be famous artists for their own gain, or find the arts intrinsically enjoyable regardless of their mainstream success, the sector is very crowded. This increases the level of competition and means only a small fraction of people who enter the industry can achieve significant success or social impact.

- While expressing your creative vision through the arts can be very fulfilling in itself, the challenges of finding work, earning enough money to pay the bills, or finding appreciation from others in a crowded field, can also be demoralising.

- Entertainment offers relatively poor opportunities to accumulate ‘career capital’. Most people who try a career in entertainment eventually leave and work in other industries. While they have built up some skills and professional networks as entertainers, most of these are not very transferrable to other industries. Some skills are transferable though: while being a skilled pianist has almost no value outside of the music industry, the ability to present yourself confidently in front of others, design marketing materials, or write well, are important in many jobs.

- While great art can entertain or improve those who receive it, there is already a great stock of art available for people to enjoy. For example, even if you write one of the best novels ever written, most people who read it would have been able to read a different outstanding novel in its absence. This argument however is weaker in the case of new art forms such as movies and TV, where a larger share of the population exhausts the highest quality of content.

- It is also reasonable to doubt the significance of the extra enjoyment people get from new art relative to the significance of suffering that can be averted by working to prevent, for example, ill-health and premature death.

- One person we spoke to raised concerns about the practicality of donating large sums to charity as a famous artist – particularly an actor or musician – given both the costs of the lifestyle involved, and the culture of opulence within mainstream arts.

If you really like art what should you do?

These ideas are at an early stage, and so should be taken as just suggestions:

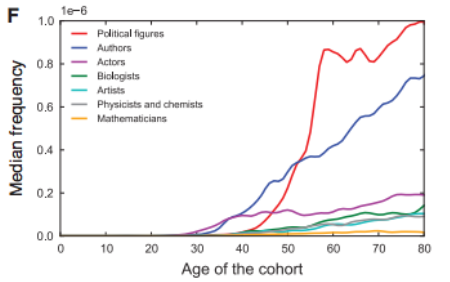

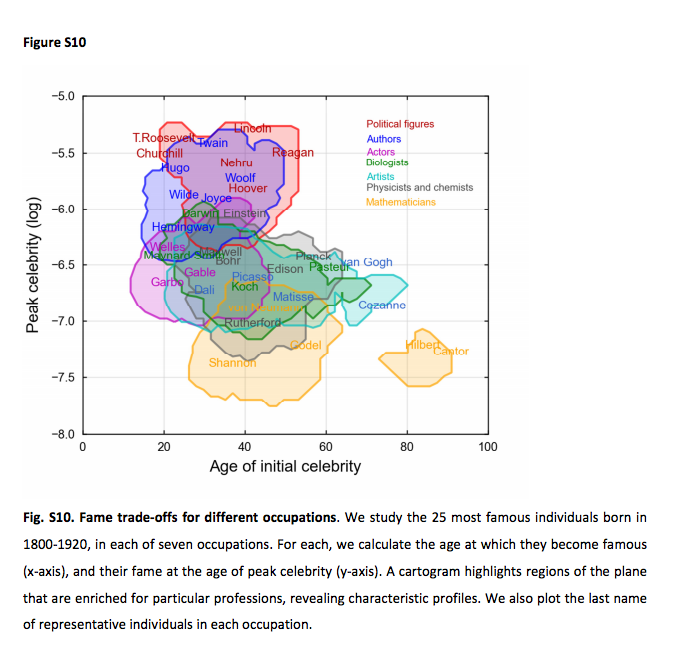

- Based on a study of the most famous figures born between 1800-1920, most actors who become famous did so by the age of 40. This suggests that after that time your odds of ‘making it’ are significantly lower, and you may wish to find a different plan. Just thinking of the most famous musicians, something similar appears to be true for them. By contrast, most writers and other artists who became famous had not done so even by age 50. 5 It also appears that there is more money available in acting and music than in publishing at this stage.

- On the other hand it seems to us that design, visual art and writing offer better exit opportunities than music or acting. For example, good writers can go into journalism, marketing and a wide range of other careers. Designers and visual artists can transition into marketing and web design, among many other things. Of course whether these careers are themselves desirable depends on the organisations and causes you are able to work for.

- Documentary film-making seems like a form of art with a good chance of direct and advocacy impact, in that it resembles investigative journalism. It also appears stronger in terms of network and transferability of skills. As a result, we would expect a career profile on documentary film-making to be more positive than this one.

- Comedy and satire also seem to offer unusually good opportunities for direct social critique and activism, as well as a reasonable transferability of skills.

Notes and references

- Bille, Trine, Cecilie Bryld Fjællegaard, Bruno S. Frey, and Lasse Steiner. “Happiness in the Arts—International Evidence on Artists’ Job Satisfaction.” Economics Letters: 15-18.↩

- Note that there is some debate about whether celebrity endorsements are effective. See discussion at: ScienceBlog and Giving What We Can Blog↩

- This argument is outlined in Steven Pinker’s book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, though it may be that enough literature of this type now exists that additions are not so useful.↩

- Lockwood, Benjamin, Charles Nathanson, and E. Glen Weyl. “Taxation and the Allocation of Talent.” Available at SSRN 1324424 (2014).↩

- Michel, Jean-Baptiste, et al. “Quantitative analysis of culture using millions of digitized books.” science 331.6014 (2011): 176-182.↩