Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article

Selected articles

Usage

The layout design for these subpages is at Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/Layout.

- Add a new Selected article to the next available subpage.

- Update "max=" to new total for its {{Random portal component}} on the main page.

Selected articles list

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/1

Medieval cuisine includes the foods, eating habits, and cooking methods of various European cultures during the Middle Ages, a period roughly dating from the 5th to the 16th century. During this period, diets and cooking changed across Europe, and these changes helped lay the foundations for modern European cuisine.Bread was the staple, followed by other foods made from cereals, such as porridge and pasta. Meat was more prestigious and more expensive than grain or vegetables. Common seasonings included verjuice, wine and vinegar. These, along with the widespread use of honey or sugar (among those who could afford it), gave many dishes a sweet-sour flavor. The most popular types of meat were pork and chicken, while beef, which required greater investment in land, was less common. Cod and herring were mainstays among the northern population, but a wide variety of other saltwater and freshwater fish were also eaten. Almonds, both sweet and bitter, were eaten whole as garnish, or more commonly ground up and used as a thickener in soups, stews, and sauces. Particularly popular was almond milk, which was a common substitute for animal milk as a cooking medium during Lent and fasts.Slow transportation and inefficient food preservation techniques prevented long-distance trade of many foods.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/2

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon (Latin: Pauperes commilitones Christi Templique Solomonici), commonly known as the Knights Templar or the Order of the Temple (French: Ordre du Temple or Templiers), were among the most famous of the Western Christian military orders.The organization existed for approximately two centuries in the Middle Ages. It was founded in the aftermath of the First Crusade of 1096, its original purpose to ensure the safety of the many Europeans who made the pilgrimage to Jerusalem after its conquest.Officially endorsed by the Roman Catholic Church around 1129, the Order became a favored charity across Europe and grew rapidly in membership and power. Templar knights, in their distinctive white mantles quartered by a red cross, were among the most skilled fighting units of the Crusades.Non-combatant members of the Order managed a large economic infrastructure throughout Christendom, innovating financial techniques that were an early form of banking, and building many fortifications across Europe and the Holy Land.The Templars' success was tied closely to the Crusades; when the Holy Land was lost, support for the Order faded. Rumors about the Templars' secret initiation ceremony created mistrust, and King Philip IV of France, deeply in debt to the Order, began pressuring Pope Clement V to take action against the Order.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/3

The Caspian expeditions of the Rus were military raids undertaken by the Rus between 864 and 1041 on the Caspian Sea shores. Initially, the Rus appeared in Serkland in the 9th century traveling as merchants along the Volga trade route, selling furs, honey, and slaves. The first small-scale raids took place in the late 9th and early 10th century. The Rus undertook the first large-scale expedition in 913; having arrived on 500 ships, they pillaged Gorgan, in the territory of present day Iran, and the adjacent areas, taking slaves and goods. On their return, the northern raiders were attacked and defeated by Khazar Muslims in the Volga Delta, and those who escaped were killed by the local tribes on the middle Volga. During their next expedition in 943, the Rus captured Barda, the capital of Arran, in the modern-day Republic of Azerbaijan. The Rus stayed there for several months, killing many inhabitants of the city and amassing substantial plunder. It was only an outbreak of dysentery among the Rus that forced them to depart with their spoils. Sviatoslav, prince of Kiev, commanded the next attack, which destroyed the Khazar state in 965. Sviatoslav's campaign established the Rus's hold on the north-south trade routes, helping to alter the demographics of the region. Raids continued through the time period with the last Scandinavian attempt to reestablish the route to the Caspian Sea taking place in 1041 by Ingvar the Far-Travelled.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/4

St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery is a functioning monastery in Kiev, Ukraine. The monastery is located on the Western side of the Dnieper River on the edge of a bluff northeast of the St. Sophia Cathedral. The site is located in the historic and administrative Uppertown and overlooks the city's historical commercial and merchant quarter, the Podil neighbourhood.Originally built in the Middle Ages by Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych, the monastery comprises the Cathedral itself , the refectory of St. John the Divine, built in 1713, the Economic Gates , constructed in 1760 and the monastery's bell tower, which was added circa 1716–1719. The exterior of the structure was rebuilt in the Ukrainian Baroque style in the 18th century while the interior remained in its original Byzantine style. The cathedral was demolished by the Soviet authorities in the 1930s, but was recently reconstructed after Ukraine gained its independence. Some scholars believe that Prince Iziaslav I Yaroslavych, whose Christian name was Demetrius, first built the Saint Demetrius's Monastery and Church in the Uppertown of Kiev near Saint Sophia Cathedral in the 1050s. Half a century later, his son, Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych, is recorded as commissioning a monastery church (1108–1113) dedicated to his own patron saint, Michael the Archangel. One reason for building the church may have been Svyatopolk's recent victory over the nomadic Polovtsians, as Michael the Archangel was considered a patron of warriors and victories.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/5

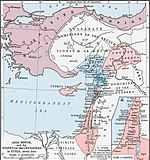

The First Crusade was launched in 1096 by Pope Urban II with the dual goals of conquering the sacred city of Jerusalem and the Holy Land and freeing the Eastern Christians from Islamic rule. What started as an appeal by Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus for western mercenaries to fight the Seljuk Turks in Anatolia quickly turned into a wholescale Western migration and conquest of territory outside of Europe. Both knights and peasants from many nations of Western Europe travelled over land and by sea towards Jerusalem and captured the city in July 1099, establishing the Kingdom of Jerusalem and other Crusader states. Although these gains lasted for less than two hundred years, the First Crusade was a major turning point in the expansion of Western power, as well as the first major step towards reopening international trade in the West since the fall of the Western Roman Empire.The origins of the Crusades in general, and of the First Crusade in particular, stem from events earlier in the Middle Ages. The breakdown of the Carolingian Empire in previous centuries, combined with the relative stability of European borders after the Christianization of the Vikings and Magyars, gave rise to an entire class of warriors who now had little to do but fight among themselves. By the early 8th century, the Umayyad Caliphate had rapidly captured North Africa, Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and Spain from a predominantly Christian Byzantine Empire.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/6

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a late 14th-century Middle English alliterative romance outlining an adventure of Sir Gawain, a knight of King Arthur's Round Table. In the tale, Sir Gawain accepts a challenge from a mysterious warrior who is completely green, from his clothes and hair to his beard and skin. The "Green Knight" offers to allow anyone to strike him with his axe if the challenger will take a return blow in a year and a day. Gawain accepts, and beheads him in one blow, only to have the Green Knight stand up, pick up his head, and remind Gawain to meet him at the appointed time. The story of Gawain's struggle to meet the appointment and his adventures along the way demonstrate the spirit of chivalry and loyalty. The poem survives in a single manuscript, the Cotton Nero A.x., that also includes three religious pieces, Pearl, Cleanness, and Patience. These works are thought to have been written by the same unknown author, dubbed the "Pearl Poet" or "Gawain poet." All four narrative poems are written in a North West Midland dialect of Middle English. The story thus emerges from the Welsh and English traditions of the dialect area, borrowing from earlier "beheading game" stories and highlighting the importance of honour and chivalry in the face of danger.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/7

The Second Crusade (1147–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe, called in 1145 in response to the fall of the County of Edessa the previous year. Edessa was the first of the Crusader states to have been founded during the First Crusade (1095–1099), and was the first to fall. The Second Crusade was announced by Pope Eugene III, and was the first of the crusades to be led by European kings, namely Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, with help from a number of other important European nobles. The armies of the two kings marched separately across Europe and were somewhat hindered by Byzantine emperor Manuel I Comnenus; after crossing Byzantine territory into Anatolia, both armies were separately defeated by the Seljuk Turks. Louis and Conrad and the remnants of their armies reached Jerusalem and, in 1148, participated in an ill-advised attack on Damascus. The crusade in the east was a failure for the crusaders and a great victory for the Muslims. It would ultimately lead to the fall of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade at the end of the 12th century. The only success came outside of the Mediterranean, where Flemish, Frisian, Norman, English, Scottish, and some German crusaders, on the way by ship to the Holy Land, fortuitously stopped and helped the Portuguese in the capture of Lisbon in 1147. Some of them, who had departed earlier, helped capture Santarém earlier in the same year.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/8

The Palace of Westminster, also known as the Houses of Parliament or Westminster Palace, in London, is where the two Houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom (the House of Lords and the House of Commons) meet. The palace lies on the north bank of the River Thames in the London borough of the City of Westminster, close to other government buildings in Whitehall. The palace's layout is intricate: its existing buildings contain around 1,100 rooms, 100 staircases and 4.8 kilometres (3 mi) of corridors. Although the building mainly dates from the 19th century, remaining elements of the original historic buildings include Westminster Hall, used today for major public ceremonial events such as lyings in state, and the Jewel Tower.Control of the Palace of Westminster and its precincts was for centuries exercised by the Queen's representative, the Lord Great Chamberlain. By agreement with the Crown, control passed to the two Houses in 1965. Certain ceremonial rooms continue to be controlled by the Lord Great Chamberlain.After a fire in 1834, the present Houses of Parliament were built over the next 30 years. They were the work of the architect Sir Charles Barry (1795–1860) and his assistant Augustus Welby Pugin (1812–52). The design incorporated Westminster Hall and the remains of St Stephen's Chapel.The Palace of Westminster site was strategically important during the Middle Ages, as it was located on the banks of the River Thames. Buildings have occupied the site since at least Saxon times.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/9

The Byzantine Empire (a historiographical term used since the 19th century) and Eastern Roman Empire are expressions used to describe the Roman Empire of the Middle Ages, centered on its capital of Constantinople, referred to by its inhabitants simply as the Roman Empire (in Greek Βασιλεία Ῥωμαίων) or Romania (Ῥωμανία), its emperors continuing the unbroken succession of Roman emperors, preserving Greco-Roman legal and cultural traditions; to the Islamic world it was known primarily as روم (Rûm, "land of the Romans"). Due to the dominance of Medieval Greek language, culture and population, it was known to many of its western European contemporaries as Empire of the Greeks. As an outgrowth of the eastern portion of Empire founded in Rome, the Byzantine Empire's evolution into a separate culture from the West can be seen as a process beginning with Emperor Constantine's transferring the capital from Nicomedia in Anatolia to Byzantium on the Bosphorus (then renamed Nova Roma, and later Constantinople). By the 7th century under the reign of Emperor Heraclius, whose reforms changed the nature of the Empire's military and recognized Greek as the official language, the Empire had taken on a distinct new character. During its existence the Empire suffered numerous setbacks and losses of territory yet it remained one of the most powerful economic, cultural and military forces in Europe.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/10

The High Middle Ages of Scotland encompass Scotland in the era between the death of Domnall II in 900 AD and the death of king Alexander III in 1286, which was an indirect cause of the Scottish Wars of Independence.At the close of the ninth century various competing kingdoms occupied the territory of modern Scotland, with Scandinavian influence dominant in the northern and western islands, Brythonic culture in the south west, the Anglo-Saxon or English Kingdom of Northumbria in the south-east and the Pictish and Gaelic Kingdom of Alba in the east, north of the River Forth. By the tenth and eleventh centuries, northern Great Britain was increasingly dominated by Gaelic culture, and by the Gaelic regal lordship of Alba, known in Latin as either Albania or Scotia, and in English as "Scotland". From its base in the east, this kingdom acquired control of the lands lying to the south and ultimately the west and much of the north. It had a flourishing culture, comprising part of the larger Gaelic-speaking world and an economy dominated by agriculture and by short-distance, local trade.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/11

The Abbey Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Bath, commonly known as Bath Abbey, is an Anglican parish church and a former Benedictine monastery in Bath, Somerset, England. Founded in the 7th century, Bath Abbey was reorganised in the 10th century and rebuilt in the 12th and 16th centuries; major restoration work was carried out by Sir George Gilbert Scott in the 1860s. It is one of the largest examples of Perpendicular Gothic architecture in the West Country.The church is cruciform in plan, and is able to seat 1200. An active place of worship, with hundreds of congregation members and hundreds of thousands of visitors each year, it is used for religious services, secular civic ceremonies, concerts and lectures. The choir performs in the abbey and elsewhere. There is a heritage museum in the vaults.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/12

The Norman conquest of England was the invasion and occupation of England by an army of Normans and French led by Duke William II of Normandy in the 11th century. William, who defeated King Harold II of England on 14 October 1066, at the Battle of Hastings, was crowned king at London on Christmas Day, 1066. He then consolidated his control and settled many of his followers in England, introducing a number of governmental and societal changes.William's claim to the English throne derived from his familial relationship with the childless King Edward the Confessor, who may have encouraged William's hopes for the throne. But when Edward died in January 1066, he was succeeded by his brother-in-law Harold, who not only faced challenges from William but also another claim by the Norwegian king, Harald Hardrada. Hardrada invaded northern England in September 1066 and was victorious at the Battle of Fulford before being defeated and killed by King Harold at the Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September 1066. William, however, had landed in southern England, and Harold quickly marched south to confront William, leaving many of his forces behind in the north. On 14 October Harold's army confronted William's invaders near Hastings and after an all-day battle, was defeated and Harold was killed.

Although William's main rivals were gone, he still faced a number of rebellions over the following years, and it was not until after 1072 that he was secure on his throne. Native resistance led to a number of the English elite having their lands confiscated, and some of them went into exile. In order to control his new kingdom, William gave lands to his followers and built castles throughout the land to command military strongpoints. Other changes included the introduction of Norman French as the language of the noble elite, the court and government, and changes in the composition of the upper classes, as William enfeoffed lands to be held directly of the king. More slowly the conquest eventually changed the agricultural classes and village life: the main immediate change appears to have been the formal elimination of slavery, which may or may not have been linked to the invasion. There was little change in the structure of government, with the new Norman administrators taking over many of the forms of Anglo-Saxon government.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/13

The Second Arab Siege of Constantinople in 717–718 was a combined land and sea offensive by the Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate against the capital city of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople. The campaign marked the culmination of twenty years of attacks and progressive Arab occupation of the Byzantine borderlands, while Byzantine strength was sapped by prolonged internal turmoil. In 716, after years of preparations, the Arabs, led by Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik, invaded Byzantine Asia Minor. The Arabs initially hoped to exploit Byzantine civil strife and made common cause with the general Leo the Isaurian, who had risen up against Emperor Theodosios III. Leo, however, tricked them and secured the Byzantine throne for himself.After wintering in the western coastlands of Asia Minor, the Arab army crossed into Thrace in early summer 717 and built siege lines to blockade the city, which was protected by the massive Theodosian Walls. The Arab fleet, which accompanied the land army and was meant to complete the city's blockade by sea, was neutralized soon after its arrival by the Byzantine navy through the use of Greek fire. This allowed Constantinople to be resupplied by sea, while the Arab army was crippled by famine and disease during the unusually hard winter that followed. In spring 718, two Arab fleets sent as reinforcements were destroyed by the Byzantines after their Christian crews defected, and an additional army sent overland through Asia Minor was ambushed and defeated. Coupled with attacks by the Bulgars on their rear, the Arabs were forced to lift the siege on 15 August 718. On its return journey, the Arab fleet was almost destroyed by natural disasters and Byzantine attacks.

The siege's failure had wide-ranging repercussions. The rescue of Constantinople ensured the continued survival of Byzantium, while the Caliphate's strategic outlook was altered: although regular attacks on Byzantine territories continued, the goal of outright conquest was abandoned. Historians credit the siege with halting the Muslim advance into Europe, and consider it one of history's most decisive battles.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/14

Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainchant, a form of monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song of the western Christian Church. Gregorian chant developed mainly in western and central Europe during the 9th and 10th centuries, with later additions and redactions. Although popular legend credits Pope St. Gregory the Great with inventing Gregorian chant, scholars believe that it arose from a later Carolingian synthesis of Roman chant and Gallican chant.Gregorian chants were organized initially into four, then into eight, and finally twelve modes. Typical melodic features include characteristic ambituses, intervallic patterns relative to a referential mode final, incipits and cadences, the use of reciting tones at a particular distance from the final, around which the other notes of the melody revolve, and a vocabulary of musical motifs woven together through a process called centonization to create families of related chants. The scale patterns are organized against a background pattern formed of conjunct and disjunct tetrachords, producing a larger pitch system called the gamut. The chants can be sung by using six-note patterns called hexachords. Gregorian melodies are traditionally written using neumes, an early form of musical notation from which the modern four-line and five-line staff developed.[1] Multi-voice elaborations of Gregorian chant, known as organum, were an early stage in the development of Western polyphony.

Gregorian chant was traditionally sung by choirs of men and boys in churches, or by women and men of religious orders in their chapels. It is the music of the Roman Rite, performed in the Mass and the monastic Office. Although Gregorian chant supplanted or marginalized the other indigenous plainchant traditions of the Christian West to become the official music of the Christian liturgy, Ambrosian chant still continues in use in Milan, and there are musicologists exploring both that and the Mozarabic chant of Christian Spain. Although Gregorian chant is no longer obligatory, the Roman Catholic Church still officially considers it the music most suitable for worship.[2] During the 20th century, Gregorian chant underwent a musicological and popular resurgence.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/15

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great. Multiple copies were made of that original which were distributed to monasteries across England, where they were independently updated. In one case, the Chronicle was still being actively updated in 1154.Nine manuscripts survive in whole or in part, though not all are of equal historical value and none of them is the original version. The oldest seems to have been started towards the end of Alfred's reign, while the most recent was written at Peterborough Abbey after a fire at that monastery in 1116. Almost all of the material in the Chronicle is in the form of annals, by year; the earliest are dated at 60 BC (the annals' date for Caesar's invasions of Britain), and historical material follows up to the year in which the chronicle was written, at which point contemporary records begin. These manuscripts collectively are known as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

The Chronicle is not unbiased: there are occasions when comparison with other medieval sources makes it clear that the scribes who wrote it omitted events or told one-sided versions of stories; there are also places where the different versions contradict each other. Taken as a whole, however, the Chronicle is the single most important historical source for the period in England between the departure of the Romans and the decades following the Norman Conquest. Much of the information given in the Chronicle is not recorded elsewhere. In addition, the manuscripts are important sources for the history of the English language; in particular, the later Peterborough text is one of the earliest examples of Middle English in existence.

Seven of the nine surviving manuscripts and fragments now reside in the British Library. The remaining two are in the Bodleian Library at Oxford and the Parker Library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/16

To be hanged, drawn and quartered (less commonly "hung, drawn and quartered") was from 1351 a penalty in England for men convicted of high treason, although the ritual was first recorded during the reigns of King Henry III (1216–1272) and his successor, Edward I (1272–1307). Convicts were fastened to a hurdle, or wooden panel, and drawn by horse to the place of execution, where they were hanged (almost to the point of death), emasculated, disembowelled, beheaded and quartered (chopped into four pieces). Their remains were often displayed in prominent places across the country, such as London Bridge. For reasons of public decency, women convicted of high treason were instead burnt at the stake.The severity of the sentence was measured against the seriousness of the crime. As an attack on the monarch's authority, high treason was considered an act deplorable enough to demand the most extreme form of punishment, and although some convicts had their sentences modified and suffered a less ignominious end, over a period of several hundred years many men found guilty of high treason were subjected to the law's ultimate sanction. This included many English Catholic priests executed during the Elizabethan era, and several of the regicides involved in the 1649 execution of King Charles I.

Although the Act of Parliament that defines high treason remains on the United Kingdom's statute books, during a long period of 19th-century legal reform the sentence of hanging, drawing and quartering was changed to drawing, hanging until dead, and posthumous beheading and quartering, before being rendered obsolete in England in 1870. The death penalty for treason was abolished in 1998.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/17

The Renaissance (UK: /rɪˈneɪsəns/, US: /ˈrɛnɪsɑːns/, French pronunciation: [ʁənɛsɑ̃ːs], from French: Renaissance "re-birth", Italian: Rinascimento, from rinascere "to be reborn") was a cultural movement that spanned the period roughly from the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. Though availability of paper and the invention of metal movable type sped the dissemination of ideas from the later 15th century, the changes of the Renaissance were not uniformly experienced across Europe. As a cultural movement, it encompassed innovative flowering of Latin and vernacular literatures, beginning with the 14th-century resurgence of learning based on classical sources, which contemporaries credited to Petrarch, the development of linear perspective and other techniques of rendering a more natural reality in painting, and gradual but widespread educational reform. In politics the Renaissance contributed the development of the conventions of diplomacy, and in science an increased reliance on observation. Historians often argue this intellectual transformation was a bridge between the Middle Ages and the Modern era. Although the Renaissance saw revolutions in many intellectual pursuits, as well as social and political upheaval, it is perhaps best known for its artistic developments and the contributions of such polymaths as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, who inspired the term "Renaissance man".There is a consensus that the Renaissance began in Florence, Italy, in the 14th century. Various theories have been proposed to account for its origins and characteristics, focusing on a variety of factors including the social and civic peculiarities of Florence at the time; its political structure; the patronage of its dominant family, the Medici; and the migration of Greek scholars and texts to Italy following the Fall of Constantinople at the hands of the Ottoman Turks.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/18

The Walls of Constantinople are a series of defensive stone walls that have surrounded and protected the city of Constantinople (today Istanbul in Turkey) since its founding as the new capital of the Byzantine Empire by Constantine the Great. With numerous additions and modifications during their history, they were the last great fortification system of antiquity, and one of the most complex and elaborate systems ever built.Initially built by Constantine the Great, the walls surrounded the new city on all sides, protecting it against attack from both sea and land. As the city grew, the famous double line of the Theodosian Walls was built in the 5th century. Although the other sections of the walls were less elaborate, when well manned, they were almost impregnable for any medieval besieger, saving the city, and the Byzantine Empire with it, during sieges from the Avars, Arabs, Rus', and Bulgars, among others (see Sieges of Constantinople). The advent of gunpowder siege cannons rendered the fortifications vulnerable, but cannon technology was not advanced enough to be decisive enough alone to capture the city, and the walls were repaired between reloading. Ultimately the city fell from sheer force of Ottoman forces on 29 May 1453 after a 6-week siege.

The walls were largely maintained intact during most of the Ottoman period, until sections began to be dismantled in the 19th century, as the city outgrew its medieval boundaries. Despite the subsequent lack of maintenance, many parts of the walls survived and are still standing today. A large-scale restoration program has been under way since the 1980s, which allows the visitor to appreciate their original appearance.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/19

The Ayyubid dynasty (Arabic: الأيوبيون al-ʾAyyūbiyyūn) was a Muslim dynasty of Kurdish origin, founded by Saladin and centered in Egypt. The dynasty ruled much of the Middle East during the 12th and 13th centuries CE. The Ayyubid family, under the brothers Ayyub and Shirkuh, originally served as soldiers for the Zengids until they supplanted them under Saladin, Ayyub's son. In 1174, Saladin proclaimed himself Sultan following the death of Nur al-Din. The Ayyubids spent the next decade launching conquests throughout the region and by 1183, the territories under their control included Egypt, Syria, northern Mesopotamia, Hejaz, Yemen, and the North African coast up to the borders of modern-day Tunisia. Most of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and beyond Jordan River fell to Saladin after his victory at the Battle of Hattin in 1187. However, the Crusaders regained control of Palestine's coastline in the 1190s.After the death of Saladin, his sons contested control over the sultanate, but Saladin's brother al-Adil eventually established himself as Sultan in 1200. In the 1230s, the Ayyubid rulers of Syria attempted to assert their independence from Egypt and remained divided until Egyptian Sultan as-Salih Ayyub restored Ayyubid unity by taking over most of Syria, excluding Aleppo, by 1247. By then, local Muslim dynasties had driven out the Ayyubids from Yemen, the Hejaz, and parts of Mesopotamia. After repelling a Crusader invasion of the Nile Delta, as-Salih Ayyub's Mamluk generals overthrew al-Mu'azzam Turanshah who succeeded Ayyub as Sultan after his death in 1250. This effectively ended Ayyubid power in Egypt and a number of attempts by the rulers of Syria, led by an-Nasir Yusuf of Aleppo, to recover it failed. In 1260, the Mongols sacked Aleppo and wrested control of what remained of the Ayyubid territories soon after. The Mamluks, who forced out the Mongols after the destruction of the Ayyubid dynasty, maintained the Ayyubid principality of Hama until deposing its last ruler in 1341.

During their relatively short tenure, the Ayyubids ushered in an era of economic prosperity in the lands they ruled and the facilities and patronage provided by the Ayyubids led to a resurgence in intellectual activity in the Islamic world. This period was also marked by an Ayyubid process of vigorously strengthening Sunni Muslim dominance in the region by constructing numerous madrasas (schools) in their major cities.

Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/20

The family of Gediminas is a group of family members of Gediminas, Grand Duke of Lithuania (ca. 1275–1341), who interacted in the 14th century. The family included the siblings, children, and grandchildren of the Grand Duke and played the pivotal role in the history of Lithuania for the period as the Lithuanian nobility had not yet acquired its influence. Gediminas was also the forefather of the Gediminid dynasty, which ruled the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from 1310s or 1280s to 1572.Gediminas' origins are unclear, but recent research suggests that Skalmantas, an otherwise unknown historical figure, was Gediminas' grandfather or father and could be considered the dynasty's founder. Because none of his brothers or sisters had known heirs, Gediminas, who sired at least twelve children, had the advantage in establishing sovereignty over his siblings. Known for his diplomatic skills, Gediminas arranged his children's marriages to suit the goals of his foreign policy: his sons consolidated Lithuanian power within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, while his daughters established or strengthened alliances with the rulers of areas in modern-day Russia, Ukraine and Poland.

The relationships among Gediminas' children were generally harmonious, with the notable exception of Jaunutis, who was deposed in 1345 by his brothers Algirdas and Kęstutis. These two brothers went on to provide a celebrated example of peaceful power-sharing. However, Gediminas' many grandchildren and their descendants engaged in power struggles that continued well into the 15th century.

Nominations

Feel free to add Middle Ages related articles Featured articles to the above list.

- ^ Development of notation styles is discussed at Dolmetsch online, accessed 4 July 2006

- ^ The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Second Vatican Council; Pope Benedict XVI: Catholic World News 28 June 2006 both accessed 5 July 2006

.jpg/150px-Bath_Abbey_(Roman_Bath_view).jpg)