This could be the most important century

Will the future of humanity be wild, or boring? It’s natural to think that if we’re trying to be sober and measured, and predict what will really happen rather than spin an exciting story, it’s more likely than not to be sort of… dull.

But there’s also good reason to think that that is simply impossible. The idea that there’s a boring future that’s internally coherent is an illusion that comes from not inspecting those scenarios too closely.

At least that is what Holden Karnofsky — founder of charity evaluator GiveWell and foundation Open Philanthropy — argues in his new article series, “The Most Important Century.”

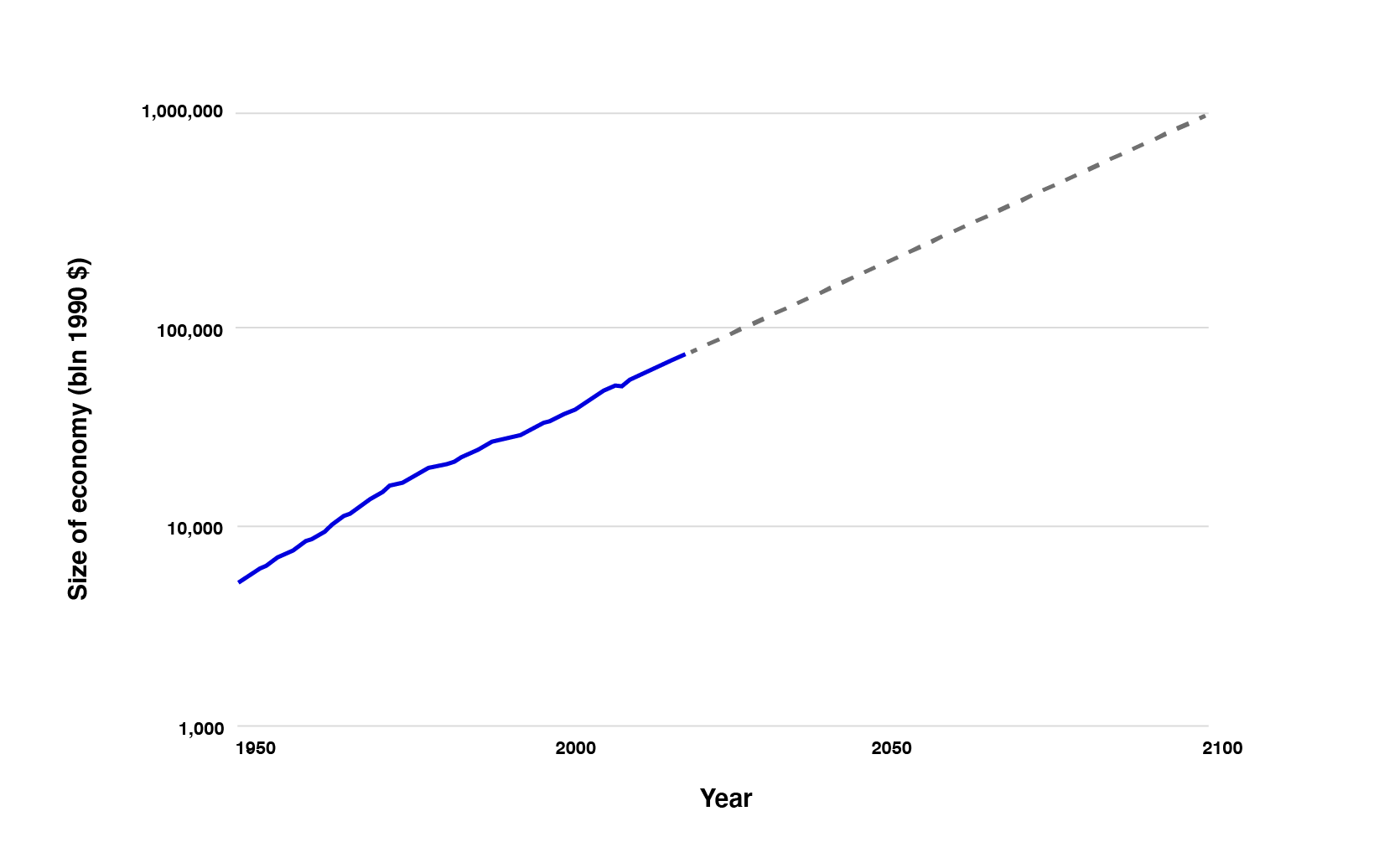

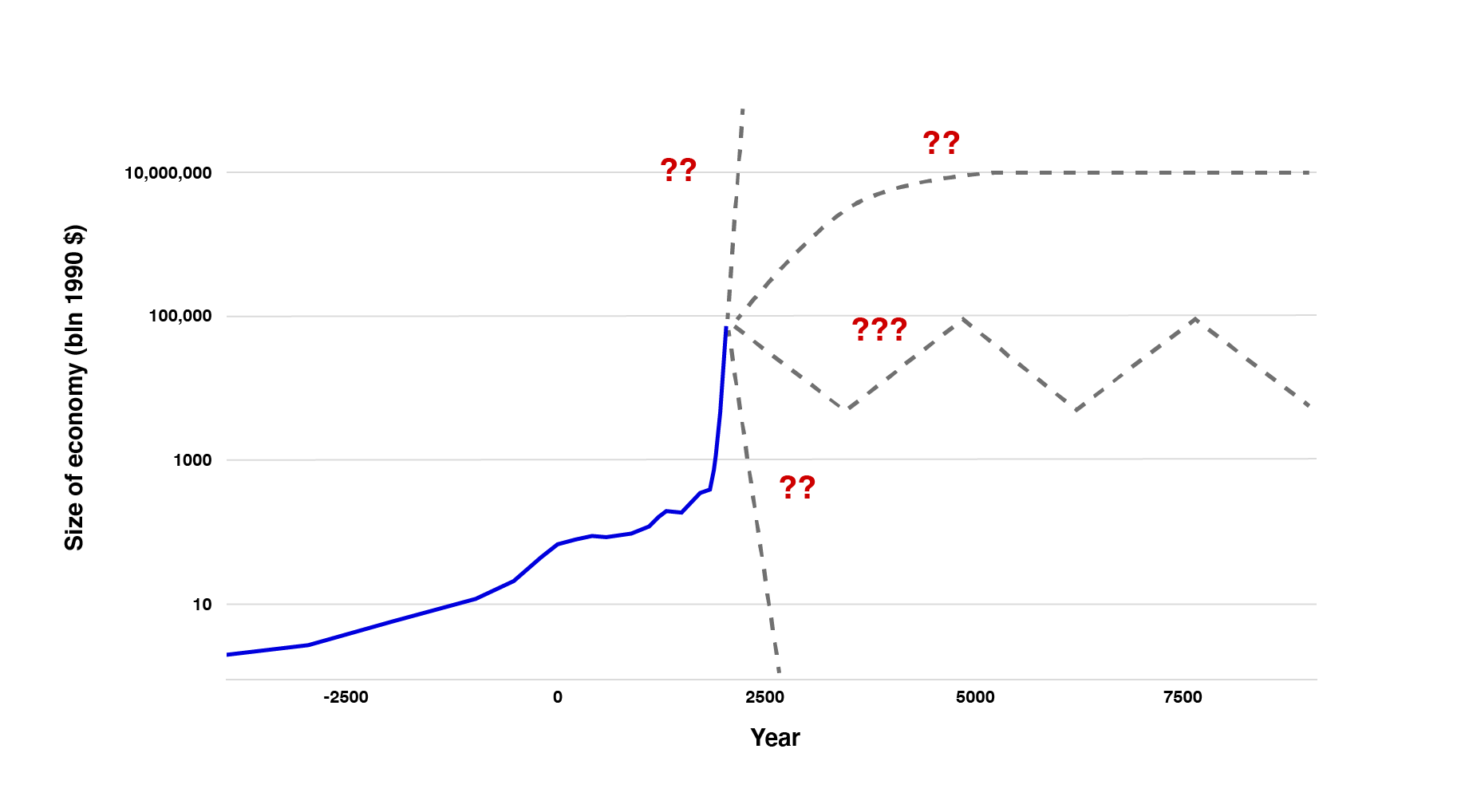

The bind is this: for the first 99% of human history, the global economy (initially mostly food production) grew very slowly: under 0.1% a year. But since the Industrial Revolution around 1800, growth has exploded to over 2% a year.

To us in 2020, that sounds perfectly sensible and the natural order of things. But Holden points out that in fact it’s not only unprecedented, it also can’t continue for long.

The power of compounding increases means that to sustain 2% growth for just 10,000 years — 5% as long as humanity has already existed — would require us to turn every individual atom in the galaxy into an economy as large as the Earth’s today. Not super likely.

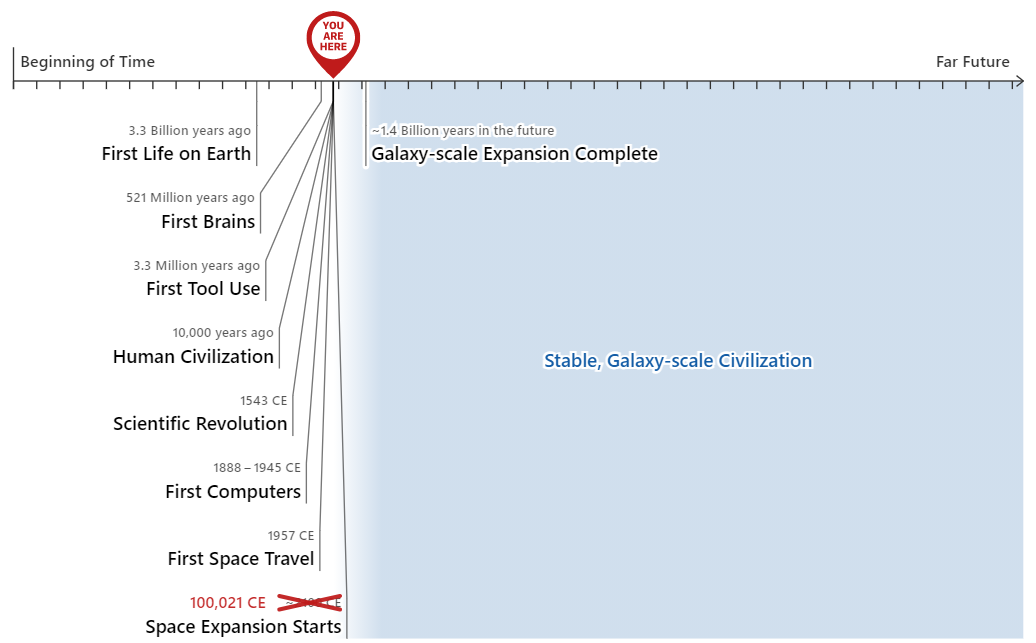

So what are the options? First, maybe growth will slow and then stop. In that case, we live today in the single miniscule slice in the history of life during which the world rapidly changed due to constant technological advances, before intelligent civilisation permanently stagnated or even collapsed. What a wild time to be alive!

Alternatively, maybe growth will continue for thousands of years. In that case, we are at the very beginning of what would necessarily have to become a stable galaxy-spanning civilisation, harnessing the energy of entire stars among other feats of engineering. We would then stand among the first tiny sliver of all the quadrillions of intelligent beings who ever exist. What a wild time to be alive!

Isn’t there another option where the future feels less remarkable and our current moment not so special?

While the full version of the argument above has a number of caveats, the short answer is “not really.” We might be in a computer simulation and our galactic potential all an illusion, though that’s hardly any less weird. And maybe the most exciting events won’t happen for generations yet. But on a cosmic scale, we’d still be living around the universe’s most remarkable time:

Holden himself was very reluctant to buy into the idea that today’s civilisation is in a strange and privileged position, but has ultimately concluded “all possible views about humanity’s future are wild.”

In the full series, Holden goes on to elaborate on technologies that might contribute to making this the most important era in history, including computer systems that automate research in science and technology, the ability to create ‘digital people’ on computers, or transformative artificial intelligence itself — and how they might create a world much weirder than most science fiction.

And if we simply project forward available computing power, or use expert forecasts, we can make a good case that the chance that these technologies arrive in our lifetimes is above 50%.

All of these technologies offer the potential for huge upsides and huge downsides. Holden is at pains to say we should neither rejoice nor despair at the circumstance we find ourselves in. His feeling is an “odd mix of intensity, urgency, confusion and hesitance.” Going forward, these issues require sober forethought about how we want the future to play out, and how we might as a species be able to steer things in that direction.

If this sort of stuff sounds absurd to you, Holden gets it.

But he thinks that, if you keep pushing yourself to do even more good, it’s reasonable to go from “I care about all people — even if they live on the other side of the world” to “I care about all people — even if they haven’t been born yet” to “I care about all people — even if they’re digital.”

If this idea is correct, what might it imply in practical terms? We’re not yet sure. You can see more of Holden’s thoughts on the implications here in the series.

One consequence is that our actions might have huge stakes, making it even more important to reflect on where to focus.

Some specific priorities that seem helpful include:

- AI alignment research — aims to ensure advanced AI systems behave in ways aligned with human values and goals, to reduce the chances that an advanced AI system causes a catastrophe. The challenge of AI alignment is that advanced AI systems could be extremely capable and may develop goals that are ‘misaligned’ with our own, potentially causing them to act in harmful ways.

- Global priorities research — a field of study that seeks to identify the most pressing problems facing the world today and develop strategies to address them. This research aims to provide a more strategic and evidence-based approach to addressing global challenges by identifying the most effective ways to allocate resources and prioritize interventions.

- Making it more likely that governments can make thoughtful, values-driven decisions. There might be ways to help important institutions improve their decision making in complex, high-stakes circumstances, especially those related to global catastrophic risks.

But most of all, we need to take this idea more seriously and understand its implications better.

To learn more, listen to our interview with Holden:

Read the full series

You can read or listen to the full series on Holden’s blog:

- All possible views about humanity’s future are wild

- The Duplicator

- Digital people would be an even bigger deal

- This can’t go on

- Forecasting transformative AI, part 1: what kind of AI?

- Forecasting transformative AI, part 2: what’s the burden of proof?

- Are we “trending toward” transformative AI? (How would we know?)

- Forecasting transformative AI: the “biological anchors” method in a nutshell

- AI timelines: where the arguments, and the “experts,” stand

- How to make the best of the most important century?

- Call to vigilance

Learn more

- Are we living at the most influential time in history? by Will MacAskill, with some reasons to be sceptical about the thesis

- Our podcast episodes with Will on the moral case against ever leaving the house, whether now is the hinge of history, and the culture of effective altruism and what we owe the future

- The emerging school of patient longtermism

- Forecasting TAI with biological anchors by Ajeya Cotra

- Podcast: Forecasting AI with Katja Grace

- New report on how much computational power it takes to match the human Brain by Joseph Carlsmith

- Modeling the human trajectory by David Roodman

- Could advanced AI drive explosive economic growth? by Tom Davidson

- Semi-informative priors over AI timelines by Tom Davidson

Read next: What are the most pressing world problems?

See the issues we think are most neglected relative to their importance, which could offer especially good opportunities to make a difference.