Transcript

Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

Hi listeners, this is the 80,000 Hours Podcast, where we have unusually in-depth conversations about the world’s most pressing problems, what you can do to solve them, and whether I’d be willing to give up Happy Meals to get rid of biological weapons. I’m Rob Wiblin, Head of Research at 80,000 Hours.

We’ve been talking about global catastrophic biological risks since our 4th episode back in 2017, and have had a lot more to say about preventing pandemics since, you know, we’ve actually been in a pandemic.

But to date something we’ve only talked about in passing are concrete policy changes that would actually help to reduce the worst biological risks specifically, rather than just control normal emerging respiratory diseases.

That’s why I was delighted to speak with Jaime Yassif, who is one of the sharpest and most spirited people in the world working on this question. She used to be a Program Officer at Open Philanthropy and is now a senior fellow focused on biological weapons control at the Nuclear Threat Initiative.

One thing I really valued about this interview was finally getting a bit more of a nuts and bolts sense of how international organizations work and where they might actually be useful.

I have to admit when people start talking about the WHO, UN agencies, arms control conventions and so on, I don’t feel like I have enough context about the actors or their motivations to tell what’s valuable, or know where listeners might be able to slot in there and make a difference. But after hearing from Jamie I feel a bit less adrift, and I hope that understanding will have some crossover value when I’m thinking about other policy areas.

We focus on a coherent set of policy proposals that aim to:

- Firstly, make it a lot harder for non-state actors to deliberately or accidentally produce a really dangerous pathogen

- And secondly, to ensure states really don’t want to do dangerous experiments or operate bioweapons programmes.

We also talk about:

- How the Biological Weapons Convention ended up without much funding or an enforcement mechanism

- Why Jaime focuses on prevention rather than response

- Jaime’s disagreements with the effective altruism community

This might all sound pretty serious, but Jaime is one of those people who is never dull to talk to.

If you think you might be interested in dedicating your career to reducing global catastrophic biological risks, stick around to the end of the episode to get Jaime’s advice — including on how people outside of the US can best contribute, and how to weigh up roles in academia vs think tanks, vs nonprofits, vs national governments and vs international orgs.

All right, without further ado, I bring you Jaime Yassif.

The interview begins [00:02:32]

Rob Wiblin: Today I’m speaking with Jaime Yassif. Jaime is a senior fellow for global biological policy and programs at the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), with a particular focus on reducing global catastrophic biological risks (GCBRs) and strengthening governance of bioscience and biotechnology. Prior to this, Jaime served as a program officer at the Open Philanthropy Project, where she recommended approximately $40 million worth of grants focused on biosecurity and pandemic preparedness. Before all that, she completed a biophysics PhD at UC Berkeley and was a science and technology policy advisor at the US Department of Defense. So thanks so much for coming on the podcast, Jaime.

Jaime Yassif: Thanks so much, Rob. It’s great to be here and I’m really excited to chat with you about reducing global catastrophic biological risks.

Rob Wiblin: I hope we’ll get to talk about how we can motivate countries to take appropriate care around global catastrophic biological risks. But first, what are you working on at the moment, and why do you think it’s important?

Jaime Yassif: Great. Something I wanted to share at the top is just a project that we at NTI are really excited about: we’re working to develop a new international organization or entity that’s dedicated to biosecurity and to strengthening governance of bioscience and biotechnology research and development.

Jaime Yassif: The reason that we’re really interested in this space is we think this work can meaningfully reduce two really important risks that are closely tied to GCBRs. One of them is deliberate attacks with engineered pathogens by malicious actors, and one of them is an accidental release with an engineered pathogen with catastrophic consequences on a global scale. So we’re really focused on reducing those risks. And if you believe that engineered pathogens are more likely to cause a GCBR than perhaps a naturally emerging pathogen, I think that’s a compelling reason to really focus on this space.

Jaime Yassif: I know we’re going to get into it in more detail later, but I’ll just tell you at a very high level that the way that we’re envisioning this organization is that its mission is going to be fairly broad. It’s going to be focused on promoting stronger global norms for biosecurity across the board, and to develop tools and systems to incentivize and make it easier to adhere to those norms — meaningful, tractable ways to concretely reduce risk. So there’s a lot of work to be done there and we’re excited about it. And we’ll talk about it a bit more later in the interview.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, I think our regular listeners will be familiar with some of the threats that we face, but we’ll give a quick primer on them again later on. So you mentioned you’re trying to start a new international organization. Is this a nonprofit, or some kind of new UN agency or something like that?

Jaime Yassif: The way that we envision this organization is it would be an independent organization. It would be nonprofit, so that it can be agile and innovative, work closely with all the key stakeholders, and keep up with rapid advances in science and technology. But importantly, in order to have legitimacy and be effective, it would work really closely with the UN System, including key parts of the World Health Organization and key parts of the UN that are associated with the Biological Weapons Convention.

Categories of global catastrophic biological risks [00:05:24]

Rob Wiblin: In terms of global catastrophic biological risks, you can cut it up into a couple of different categories. I suppose one is active military bioweapons programs. Another one might be accidental releases of something dangerous from legitimate scientific research labs. And I guess the third category is just natural pandemics that happen to be extremely bad. How does the magnitude of the risk across these things compare, do you think, and which one are you guys focused on primarily?

Jaime Yassif: Absolutely. I think your description of the three buckets is roughly right. There are deliberate risks that could come from either state actors or non-state actors. There is accidental release that could come from a wide variety of sources. And then there are naturally emerging infectious disease outbreaks and pandemics. I think a lot of different people in the community have speculated about which pose a greater threat and which is most likely to pose a global catastrophic biological risk. And we don’t have enough evidence to say definitively that we know it’s A and not B or vice versa.

Jaime Yassif: I think the argument within parts of the biosecurity community and parts of the effective altruism community that I identify with is that engineered pathogens pose a more significant risk from a GCBR perspective than perhaps naturally emerging infectious diseases, at least in the long term. They’re much more likely to cause a global catastrophic biological risk, in my view.

Jaime Yassif: And therefore, we should really focus on the kinds of pandemics that can be caused by human activity — either a deliberate attack or an accidental release of a pathogen that has been engineered in a laboratory. And in fact, at NTI, our bio team is working to reduce risks across the board, but we’re primarily focused on reducing deliberate and accidental release risks. That’s where we feel that we have a comparative advantage.

Rob Wiblin: I guess that makes a lot of sense, given that the Nuclear Threat Initiative’s background is working on nuclear nonproliferation and control and weapons issues. So I suppose it’s natural for you to take on the issue of bioweapons, and other irresponsible production of dangerous material.

Jaime Yassif: I think that’s close to how we would view it at NTI. We view our mission as reducing catastrophic risks to humanity that could imperil our long-term future, and that could come from nuclear or biological sources. We don’t necessarily have a bias towards human-caused events, but we want to address the risks that we believe are most significant to the long-term future of humanity, so we can build a safer world. And so we’re very strategic about how we prioritize our time and our efforts.

Disagreements with the effective altruism community [00:07:39]

Rob Wiblin: We’ve got a lot of listeners who are in some way involved with the effective altruism community. What do you think that broader group, like the listeners to the show or perhaps me, are most likely to get wrong about global catastrophic biological risks?

Jaime Yassif: There are a couple areas where I feel like I’ve had spirited debates with my very smart colleagues in the effective altruism community. And I have a lot of respect for the EA community. I really appreciate how rigorous people are when they think about these problem sets. And I think they’ve really challenged our community to think harder about how we prioritize our efforts and how we can really most meaningfully address catastrophic biological risks. So first of all, I want to give credit where credit is due.

Jaime Yassif: But I will say that I think where we’ve had differences of opinion are two key areas. One phenomenon I’ve noticed in the effective altruism community is that sometimes people like to identify one big thing that could happen that is the most important thing, and it’ll be 1,000 or 100 times more effective than anything else you could do. And I think there’s a desire for us to identify what that is in biosecurity and dedicate a vast majority of our resources and time to that one thing.

Jaime Yassif: And I am skeptical of that approach, personally. There is a chance that maybe as we look back, there may have been things that we have done that were more effective at reducing risks, but a priori I think it’s very difficult to tell. And I think it’s really important to have a layered defense that has multiple theories of risk reduction. I don’t believe that there’s one silver bullet.

Jaime Yassif: Related to that, something that I consider to be an open question is, what is the greatest source of global catastrophic biological risks? Should we be worried more about states or non-state actors? I’m concerned about both. In the long term, it’s not obvious to me that we should focus exclusively on one or the other. I think both are significant risks, and we shouldn’t ignore non-state actors, for example. I think some folks in the community think that states are a greater risk.

Jaime Yassif: And then the third thing I would add is that sometimes I notice in the EA community there’s a real excitement about finding technology solutions to problems. And I think technology solutions are fabulous and a really important tool. And sometimes they’re very attractive because it’s easier — you don’t have to build broad coalitions to support tech. You just develop the technology —

Rob Wiblin: Fewer conversations.

Jaime Yassif: There are aspects of that that I personally find appealing. But I would stress that you can’t solve all the problems with technology and you do have to work with people and institutions sometimes. And even though that’s messy, sometimes you’ve got to do the hard work to drive institutional change, to really have sustainable solutions. So those are some of the ongoing conversations that we’re having about areas where we don’t necessarily agree.

Rob Wiblin: Something I noticed preparing for this interview is that it seems like the conclusion is that there isn’t a silver bullet here. Instead, you just need to layer a bunch of different risk reduction methods on top of one another, and each one maybe halves the risk, and then collectively, they’ve made a really huge difference.

Rob Wiblin: I had this vague sense that in the past, people might have gotten a bit stuck by the search for the silver bullet — they couldn’t find anything that would by itself solve the problem, or even solve the problem 90% or anything like that. And so then they were like, “Well, I guess we should just keep on researching and trying to find something.” But maybe the way forward is instead this approach of having five or 10 different things that you do, each of which reduces the risk more like 50%, or perhaps 30%.

Jaime Yassif: I think that’s basically right. And in defense of the effective altruism community, I don’t think this community is the only community that has fallen into that mode of thought. In recent years and recent decades, as our community has struggled to find really effective ways to reduce risks and threats in the bio space — anytime you come up with any solution, people can poke holes in it. And it’s very tempting to say, “Oh, well, it’s not a 100% solution” or “There are big holes in it and therefore that’s not an answer and we should drop it.”

Jaime Yassif: I think that’s a mistake. Having tried to develop multiple solutions and continuing to go through that pattern, I’ve decided that just because something has holes or it doesn’t reduce the risk by 100% doesn’t mean we should drop it. And then in terms of this layered defense, I absolutely believe that that’s the way to go.

Jaime Yassif: When I was working at Open Phil as a program officer, we had a conversation that I thought was a really helpful way to talk about it in simple terms, which is: you find all the biggest holes in the system, and you try to plug the biggest holes first. So I’m not making an argument that we shouldn’t prioritize. We absolutely should, and there are a priori ways to figure out what are more and less impactful things we can do. But I think we shouldn’t reduce the list down to one or two actions. It should be a longer list.

Stopping the first person from getting infected [00:11:51]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Makes sense. Broadly speaking, you could split trying to stop catastrophic pandemics into two different approaches. One would be to stop the first person getting infected at all. And then another approach is trying to stop the pandemic from spreading from that point — so trying to detect the pandemic early and then contain it or come up with treatments really quickly. It sounds like you’re basically focused on the first one — stopping the first person from getting infected. Why focus on that stage?

Jaime Yassif: First of all, I believe that again — keeping with my layered defense mantra here — I think prevention, detection, response are all critical elements. And I think for the world to be safer from pandemics and global catastrophic biological risks, we need to do all three. I think we need a division of labor in the community. I think others in the community are doing a lot of great work on early detection and response.

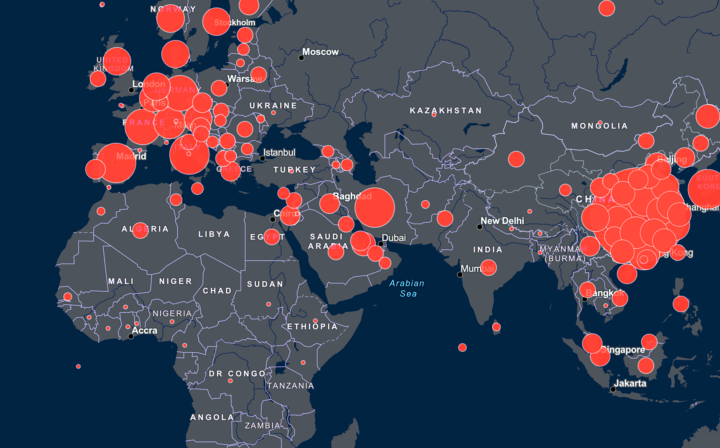

Jaime Yassif: Our bio team at NTI is engaged in some efforts that are related to early detection and response, including our Global Health Security Index — where we’ve done an assessment of 195 countries and looked at their pandemic preparedness capabilities across the board, and tried to draw attention to the need to fill those gaps. So we really believe in the full spectrum of activities, and we are, in fact, working on them.

Jaime Yassif: The work that I personally as an individual am engaged in is more focused at the moment on prevention. But that’s just because I see really big gaps in the area — I think it’s more of a neglected area than some of the other areas. And so I think the marginal impact that I individually can have on the space is greater by working on prevention, though it is a challenging area to work.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Just briefly on the containment side of things, I don’t know whether you’ve heard the Andy Weber interview that we did earlier in the year. Or possibly you’ve heard his opinions elsewhere, because I think he tends to talk about them quite a lot. But he has this proposal for containing potential GCBRs, where I guess you try to get DNA sequencing all over the place so that we can detect any new biological threats really quickly.

Rob Wiblin: And then he thinks we should have a system for very rapidly developing new mRNA vaccines against any new pathogens, which is really great because mRNA vaccines are kind of a platform that you can quickly adapt to new pathogens. And then also have in mind a system for really quickly vaccinating the whole world against any new pathogen with these vaccines that we hopefully develop within weeks or months. Do you have any thoughts on that? Is that something that excites you, even though it’s perhaps not as much within your wheelhouse?

Jaime Yassif: First of all, I used to work for Andy Weber. Back when I worked at the Department of Defense in government, he was an Assistant Secretary and I worked for him and his team at the Department of Defense. I’m a huge fan of Andy Weber and his work, and we’re really lucky to have him in the field. So I’ll just start with that.

Jaime Yassif: Second, I’ll say that I totally agree with the ideas that he is advocating for, and that we should absolutely invest in those capabilities. I think early detection and building a more robust biosurveillance system nationally and globally — and one that includes sequencing — would be incredibly valuable for early detection for the reasons that you state. If we can contain pandemics before they turn into pandemics early, that’s a huge gain in terms of risk reduction.

Jaime Yassif: Likewise, I’m a huge fan of platform technologies for medical countermeasure development, and mRNA technology is the leading technology that’s most advanced and most promising at the moment. There may be other technologies that become an option in the future, and we should consider those as well. The days are gone where we think about one bug and one drug, and then we stockpile vaccines for known pathogens. If we want to look to the future and reduce risks meaningfully, we have to be prepared for a surprise. So a platform technology that can respond in an agile way to quickly develop a new medical countermeasure in response to a new threat is absolutely the way that we need to go. We should pour lots of resources into it.

Jaime Yassif: However, like any system that we develop to reduce risks, there are going to be failure modes. And that is just a feature of this space. And so we absolutely should do all those things and we should also do prevention as well. We should not have a single point of failure. If this is really part of a shared global effort to safeguard the future of humanity, we need to intervene at every point possible — prevention, detection, and response — to reduce the risk as close to zero as we can that we would face something catastrophic from a biological release in the future.

Jaime Yassif: So I’m really grateful that Andy’s working on those issues, and would love to see those things come to pass, in addition to all the other ideas that we’ll be talking about today.

Shaping intent [00:15:51]

Rob Wiblin: All right. So on that note, let’s push into the meat of the Nuclear Threat Initiative agenda on GCBRs. At a high level, NTI’s work to prevent GCBRs I think you can see it as broken down into two parts, which you call “constraining capabilities” and “shaping intent.”

Rob Wiblin: Constraining capabilities is focused on limiting what dangerous things malicious actors like rogue groups are able to do by exploiting legitimate academic research science or the work that’s coming out of biotech companies. And we’ll come back and deal with that stream later on in the conversation.

Rob Wiblin: But I actually want to start with this idea of shaping intent, because I think it’s super interesting. The basic idea here is that if a powerful or well-resourced country wants to do some dangerous thing with novel bioscience, then in your view — and I think by my view as well — there’s not a whole lot we can do to stop them from being able to buy the equipment or hire people to pursue that idea, if they’re really committed to it. Maybe we could slow them down a little bit, but that doesn’t really get us where we want to be, which is really discouraging that dangerous kind of activity by states.

Rob Wiblin: And that means that instead we need to focus on this other approach, which in short, is making states not want to do dangerous experiments or run bioweapons programs. Because if a country thinks it’s clearly not in their interests to do so, then they probably won’t do it and that will be good. What’s the key mechanism we have for shaping the intent or motivations of states and other big actors whose capabilities are hard to constrain?

Jaime Yassif: Absolutely. So I want to start by just explaining why a rational country, or perhaps an irrational country sometimes, might decide to pursue a biological weapons program or even use a biological weapon. So I think that there are two sets of motivations — or three, actually — that we should really be thinking about when we’re trying to shape intent.

Jaime Yassif: One of them is just fear of what their adversary might be up to. So recognizing that right now, there’s not as much transparency among states about what is going on with regard to biodefense and bioscience and biotechnology development. There is a risk that there could be misperceptions, that there could be escalating suspicion, and that could lead to an undesirable future where you have arms racing behavior.

Jaime Yassif: So that’s a future we really want to avoid. And a way that you address that is through increased transparency. Transparency is helpful in the sense that if, in fact, the vast majority of states aren’t in violation of the Biological Weapons Convention, that would just help clarify that. And to the extent that transparency could actually bring to light where there are violations, that’s also information we want to know.

Jaime Yassif: On the other hand, I think there’s another set of motives. Let’s assume a country isn’t necessarily being driven by fear, but they think that they have some sort of strategic or tactical advantage for having a biological weapon, and there may be some instances where they could get away with something. That they could launch an attack — maybe in a targeted way, maybe in a way that’s clandestine.

Jaime Yassif: And because current international tools for attribution and accountability are not, in my view, what they should be, they might not get caught. Or if they are suspected of doing something, that they wouldn’t be held accountable and they could get away with it. And I think that we need to change that to the extent that that’s true. There are a lot of tools and systems we can build up in the international community to strengthen deterrence regarding bioweapon development and use.

Jaime Yassif: I do want to also note that a lot of the times when you think about shaping intent, it’s assuming rational action. Sometimes institutions do have irrational behavior, and there’s some historical evidence of this. Even if at the highest levels governments don’t want to develop a bioweapons program, there might be strange activities within large bureaucracies — if there are weird institutional drivers for an individual scientist or for an individual institution seeking budgets to push in a certain —

Rob Wiblin: Or a company?

Jaime Yassif: Company less so. I think that is a different set of incentives. And I still think that a lot of the bigger-picture ideas we’re focused on in terms of shaping rational decision-making could address those motives as well. But those are the three paths in my view that you can imagine getting to a bioweapon development program. And I believe that it’s plausible that effective action in this space to build stronger institutions and capabilities could dissuade a country from seeking to develop a new program or explore new research that crosses the line.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So I guess if a country is rational, then making it more likely that their violation of the Biological Weapons Convention would be detected and they would face some negative consequence, that should make them less likely to want to pursue it. Even a country that’s irrational, if they’re pursuing a bioweapons program — in a sense, foolishly or against their own interests — I suppose just piling on the probability of detection and the scale of the consequences they might face still might push them over the line, even if they’re not assessing things completely rationally.

Rob Wiblin: You’ve raised this issue of a potential arms race with biological weapons and our past guests have raised that as well. But I’m just imagining that scenario, where country A and country B do not have amicable relations, and A suspects that B has a biological weapons program — would A really benefit that much from establishing their own bioweapons program? How does that really help them to defend themselves? They could just invest in all kinds of other military stuff that isn’t related to bioweapons programs. I guess I’m not quite understanding how it exactly assists them in the arms race situation.

Jaime Yassif: Sure. I think that’s a fair question. And I’m certainly not trying to justify the development of biological weapons or encourage any state to seriously consider it — that’s definitely not my position, just to be very clear. But I think if you want to really understand where the rationale might come from, I think some people are concerned that bioweapons could be viewed as an asymmetric weapon.

Jaime Yassif: So if you’re a superpower and you’ve got lots of resources, then it’s easy to build up very strong conventional capabilities that are very effective in deterring adversaries from attacking you, and actually can be used in warfare. And there’s no moral or humanitarian norm against using conventional weapons. But those are expensive and hard to develop, and having an edge in conventional terms is hard.

Jaime Yassif: A nuclear weapon is an asymmetric weapon. And there have been some discussions about how that dynamic works, and we need to work to disincentivize development of nuclear weapons. But I would say the threshold for developing a biological weapon is even lower, because dual-use bioscience and biotechnology, knowledge, tools, resources — they’re widely distributed. And so there’s just a lower barrier to entry, so you could imagine a country saying, “Well, I can develop this asymmetric weapon at lower cost, and it’s more accessible to me than these other means of military dominance or deterrence.”

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Before we turn to the new ideas for deterrence, maybe let’s talk about the things that we already have. A lot of people will know that the US in the past has used military force against countries that they suspect, or purportedly suspect, of having biological or chemical weapons. Famously, Saddam Hussein in the 90s and then again in 2003, and the threat of force was used against Syria throughout the 2010s regarding their potential chemical weapons. To what extent can the problem of bioweapons be solved this way?

Jaime Yassif: I know the US has played this role in the past. And I guess I would say I wouldn’t want to build an entire international arms control regime based on an assumption that the US is going to police the global order. I don’t think it’s a reliable approach. I think it’s a very last resort, and fundamentally, it’s not always legitimate in the eyes of the international community and it’s messy — it involves conflict and a lot of innocent people that die on both sides.

Jaime Yassif: By the time you get to that point, there’s a lot of cost. And so I think we are much safer if we can get upstream of this and just prevent countries from exploring this in the first place — and not get to a point where weapons development or production may have commenced, and we’re trying to bomb it out of existence. I think that’s a really tough place to be, and it’s not a theory of change that I think is…

Rob Wiblin: Ideal.

Jaime Yassif: Yeah. Nor is it really… You know, a lot of countries around the world don’t find that to be a legitimate international tool.

Rob Wiblin: To what extent then might we be able to rely on robust biosecurity intelligence capabilities to be able to detect any bioweapons programs that the country might be initiating?

Jaime Yassif: I want to step back for a second and discuss the big picture of what I think is the positive case for what we can do to shape intentions. And then I’m happy to talk about intelligence.

Jaime Yassif: My recipe for more robust systems is that we need more effective transparency for the reasons I said before, which is to reduce the risks of arms racing and reduce the risks of misperceptions that could lead to arms racing. And people have talked about that in the past as verification. I think that verification is a complicated word with a long history — and we can unpack that in a few minutes if you’d like — but I think that there’s work to be done there.

Jaime Yassif: The second piece is, I think we need more effective means of investigating the origins of a high-consequence biological event if and when it does occur, so that there is an internationally legitimate, evidence-based, transparent process to actually effectively run that to ground, and fairly quickly. That’s important. I would argue that we don’t really have the full suite of capabilities that we need to get there, and we have a lot of work to do there too, and I see an opportunity.

Jaime Yassif: The third piece is accountability. If we are in fact able to reliably attribute the source of an attack or an event to either a state or a non-state actor, they should be held accountable in ways that would actually be meaningful. That’s hard, but I do think it’s necessary.

Jaime Yassif: So I just wanted to paint a big picture. In addition to all those things I said, in terms of trying to get upstream of risks and anticipating them early before they’re fully present, if we want to really be effective at preventing high-consequence biological events, we as an international community should get better at anticipating threats. I think there’s a lot of opportunity for governments and countries around the world to invest more in intelligence gathering for biosecurity threats — to see if other states or non-state actors might be interested in developing biological weapons, or if they’re actively engaged in those pursuits. We should get better at detecting that early and really dedicate more resources. I think there’s a lot of value in that.

Verification and the Biological Weapons Convention [00:25:34]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So you mentioned verification. I guess famously the Biological Weapons Convention doesn’t really have a verification or any enforcement mechanism, and it only has about three staff or something like that. Why that’s the case is an interesting story that you put me onto when I was preparing for the interview. Your focus isn’t history here, but it’s relevant because there was this big push to add a verification mechanism in the 90s — which ended up not panning out, which I guess we need to learn from. What was the setup there?

Jaime Yassif: Absolutely. Yeah, so as you point out, the BWC doesn’t have a verification regime. It also lacks a large institution to support it: the only support it has institutionally is a three-person Implementation Support Unit. Its annual budget is $1.5 million a year. Some of our friends in the effective altruism community have pointed out that that’s roughly the cost of running one McDonald’s restaurant in a franchise for a year — which is just not the right level of spending in my view and in many people’s view for this really important global institution.

Rob Wiblin: Seems like it’s doing more important work.

Jaime Yassif: Yeah. I would argue the case for that is pretty clear. But in terms of the verification piece, there was a very vigorous attempt made in the 90s — there were a series of measures that were part of the process in the 90s to try to develop a verification mechanism. Back in 1991 at the BWC Review Conference, the States Parties agreed to establish something called VEREX, which was tasked with preparing a technical report on the feasibility of potential verification measures, recognizing, “Hey, there have been some advances in bioscience and biotechnology. It’s the ’90s, and what can we do that’s different than what we might have been able to do before?”

Jaime Yassif: And then a few years later, in 1994, as part of a special conference in Geneva I believe, the States Parties established something called an Ad Hoc Group. And that actually had a mandate to negotiate a verification protocol. That was a big deal at the time. And so over the next seven or eight years, the States Parties to the BWC undertook serious efforts to negotiate what that agreement might look like.

Rob Wiblin: And this included how many countries? Is this every signatory to the BWC, which is almost 200?

Jaime Yassif: That’s right. All the States Parties at the time. There were fewer at that time than there are now, but —

Rob Wiblin: Still a handful.

Jaime Yassif: Yeah. Roughly, I think 170 or 180, I would guess at the time, States Parties to the BWC — a very large group. I’ll tell you what the punchline was at the end game and then I’ll back up and tell you why this didn’t work out. So at the end of the day, in 2001, the chairman of the BWC meeting had this compromise text, and it basically captured all the different positions and the open questions associated with the negotiation. It was a text that the States Parties were going to try to refine to come to an agreement.

Jaime Yassif: What happened is basically the United States government walked away from the negotiations. They withdrew their support from this text and this process. And I think a lot of people will show up at meetings and say, “Oh, well, the United States is the reason that this didn’t happen and they’re to blame.” And I think that that’s facile and I don’t think it’s fully accurate, and it’s much more complicated than that — it kind of gets into the politics of the BWC as an institutional body and also the history of the discussions.

Rob Wiblin: So the proximate cause, the cause that was very visible to journalists, I guess, who hadn’t been following this closely was —

Jaime Yassif: And just political figures and countries around the world. It’s very convenient to blame the US, you know?

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So there was John Bolton, right? This somewhat bellicose, somewhat aggressive US diplomatic figure under the Bush administration. They walked away from the table, said, “This is pointless, we’re out.” But there were far deeper reasons why they walked away, and probably it wouldn’t have made any difference if they’d stayed. Do you want to explain why?

Jaime Yassif: Yeah. I’m happy to unpack that. And I just want to make it clear that I’m not a historian, but this particular issue is really important to me. And my thinking about this topic is shaped by some writing done by Kenneth Ward. There’s a really great paper in The Nonproliferation Review that some folks might want to check out. It’s called “The BWC protocol mandate for failure.”

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. It’s a cracker.

Jaime Yassif: It’s great. And I’ll readily acknowledge that it is very much a Western perspective and a US perspective, and I don’t agree with 100% of the things that he says. But I do think he makes some really compelling arguments about some of the underlying causes for why this fundamentally was a very weak process that was unlikely to succeed as it was constructed.

Rob Wiblin: Was he a negotiator in the process? Or just an observer?

Jaime Yassif: Yes, I believe that he was a negotiator in the process. So he participated, he viewed it up close, and he was associated with the US government. So obviously he’s not an unbiased observer, and so you can take his perspective with a grain of salt.

Jaime Yassif: But basically his argument, which I think sounds very plausible, is that… So something that’s important to understand generally about the BWC is it’s not almost 200 individual countries acting as individual actors. It’s broken into these three blocs that are really a historical artifact of the Cold War.

Jaime Yassif: You’ve got the Western group, which is comprised of Western countries — many of which are allied with the US — you’ve got Europe. You’ve got the Eastern bloc, which is a group that’s associated with the former Soviet Union and countries that are closely allied to them. And then you’ve got the Non-Aligned Movement, which is a lot of countries from the Global South, developing countries. And they all have slightly different interests, and those interests came forth in this discussion.

Jaime Yassif: So here were the challenges: the Non-Aligned Movement, fundamentally, as part of these protocol negotiations, they were really advocating for development assistance. They wanted to weaken some of the export controls, including the Australia Group, so they could have access to technology. Technology transfer is important to them, and they wanted also financial assistance to build their own capability —

Rob Wiblin: Biotech industries.

Jaime Yassif: Exactly, exactly. And so —

Rob Wiblin: What’s the Australia Group?

Jaime Yassif: The Australia Group is a group of like-minded countries, mostly Western, that have agreed upon export controls of key technologies that are associated with potential weapons of mass destruction. And so it constrains the export of certain knowledge or goods to certain countries that could otherwise lead to proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

Rob Wiblin: Some poorer countries, some developing countries, weren’t keen on this, because they saw it as limiting their scientific research development or their economic development. And so they wanted to see those kinds of export controls reduced and maybe even countries like Australia or the US paying to build a biotech R&D industry or sector within their countries.

Jaime Yassif: Yeah. So they’re emphasizing economic development assistance and weakening of certain export controls as part of their positioning in the context of these discussions. And so that was what they were pushing for, which was viewed by others as a threat to the nonproliferation regime and could actually exacerbate proliferation and weaken the BWC overall. And so that was a dynamic that was underway.

Jaime Yassif: And there were some other countries that had other agendas. I’m not going to name names. But there were certain countries that were trying to create a list-based approach to what is considered a biological threat, instead of having a general-purpose criterion and saying, “If you have intention to weaponize this, it’s already crossing the line.” Redefining what it means to violate the BWC to a list-based approach, where you basically define “Within these quantities and these categories of pathogens, this is a violation” — and therefore implicitly things that fall outside this specific list have what it was perceived to be a quote unquote “safe harbor.” And so again, to some other countries, including in the West, there was a concern that this could create big holes in the BWC in terms of what is considered a violation, which could undermine the Convention.

Jaime Yassif: And then a third thing is… Part of what would be an effective verification mechanism would include challenge inspections — that’s commonly found in other regimes. So some countries were trying to weaken the challenge inspections provisions by saying they would have to pass through the UN Security Council, in which certain countries have veto power. So all of these things were viewed by others as really weakening what was possible, and weakening the BWC, and untenable.

Jaime Yassif: And so there were a lot of big open questions about which countries weren’t able to reach agreement. Not to mention the fact that even within the Western group, there wasn’t full agreement about the extent and scope of what this verification regime would look like. It was a really challenging negotiation, and really entrenched positions in different political groupings. It wasn’t clear that they were ever going to arrive at some sort of consensus statement about what was going to work that was going to be meaningfully strengthening BWC instead of weakening it.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So the Biological Weapons Convention operates on consensus. So every country that’s party to it, in order to change it, would have to agree to change the rules, right?

Jaime Yassif: That’s right, the BWC is a consensus-based decision-making body. And so it is in fact very challenging to agree on big changes with that kind of approach.

Rob Wiblin: Okay. So you need a consensus, and as you’ve laid out, there were different priorities — definitely competing priorities — between the different countries. It kind of surprises me that people spent seven or eight years trying to reach consensus when it seems like it might have become apparent fairly quickly that that was never going to happen.

Jaime Yassif: I don’t think everyone shared the view that it wasn’t going to happen. I mean, I’ve spoken with people about the plausibility of revisiting the question of verification or thinking about it in a new light — refreshing the conversation. People who were involved in those negotiations… I think some of them believed that the solution was in sight and they just needed more time and more political space. I’m not in the minds of the people who were involved in those negotiations, and I certainly wasn’t there at the time, but I believe that the people who were engaged in it in earnest genuinely had faith that a solution was within reach.

Jaime Yassif: And I do believe generally — notwithstanding how challenging it can be to advance progress within a consensus-based decision-making body — I think that if you can get enough of these divergent political groups to align their interests… I mean, we do have a lot of shared interest in building a safer world. We do have a lot of common interests. I can imagine a future where this body could really change its political dynamics and be more constructive and make progress with a consensus-based decision-making process.

Jaime Yassif: But the current political blockings and the current dynamics are just not conducive, and we need to have a radically different environment. And that’s going to take a lot of smart young people who are energized and participating from a lot of different countries with a different view that really are earnestly trying to tackle this issue. And I’m hoping that members of the effective altruism community can help us be part of that solution.

Rob Wiblin: So most countries care about bioweapons control to some greater or lesser degree, but it seems like the great majority don’t care about it as much as you and I do. What do you think is the main reason for that?

Jaime Yassif: I think there are a couple things going on here. One of them is that a lot of countries very legitimately are focused on reducing the risks posed by naturally occurring infectious disease outbreaks and pandemics. Because they’re facing those risks every day, it is a drain on their economy, it’s a drain on their workforce, and it kills their publics. And so that’s what’s in front of them now and they need help with that now. And I think that is a totally understandable position.

Jaime Yassif: A lot of Western countries or countries with a lot of money don’t have to deal with that as much, because we just have more resources to have public health and sanitation. But other places are really struggling, and I think it’s totally understandable and valid for them to be focused on the issues that are really pressing for them. We really need to be cognizant of that and sympathetic to that if we’re going to work together with those countries to build a safer world. We have to understand their perspective.

Jaime Yassif: As part of that, there are also just different threat perceptions. I think a lot of countries view deliberate biothreats as a problem of the US or a problem of the West — as an invented problem that’s not as significant in their minds as we view it in the West. And so it’s just different threat perceptions.

Jaime Yassif: I think part of that is also that they don’t have as advanced bioscience and biotechnology infrastructure, and they would like to have it. So for them a priority is developing that infrastructure — that’s step one. Step two is reducing the risk associated with it, but they want to have the infrastructure to begin with. So I think that there’s a lot going on. And part of this is just a North–South divide issue.

Attribution [00:37:19]

Rob Wiblin: Okay. So that’s a bunch about the verification and the Biological Weapons Convention. Let’s talk now about attribution, because I suppose a really important part of giving countries incentives not to do dangerous things is that we need to be able to identify after the fact who has done something wrong — like where a pathogen has come from, if it was caused by human action, so there can be some consequences. What mechanisms are there currently for attributing the sources of new diseases?

Jaime Yassif: There are two major tools that are in place right now. One of them resides within the World Health Organization, and the World Health Organization has a strong comparative advantage in investigating the origins of naturally emerging infectious disease outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics. The UN System also has the UN Secretary-General’s Mechanism, which has the authority to investigate allegations of deliberate misuse of biological weapons, meaning bioweapons attacks.

Jaime Yassif: One thing I’ll say about WHO is in light of everything that’s been going on right now — the controversies about the origins of COVID — WHO has been working in earnest to make their capabilities more robust to deal with these edge cases where the origins are uncertain. And a lot of people in WHO would stress that the International Health Regulations, which provide them with their authorities, also give the authority to investigate origins of events that are not natural.

Jaime Yassif: I think that part of the issue there is a capabilities gap. The WHO even in recent weeks has been working very publicly to set up this new Scientific Advisory Group for the Origins of Novel Pathogens (SAGO). And they recently announced the members of this advisory group, which are scientists from around the world. I think that’s great. I really applaud WHO’s efforts to expand the scope of their work in this area. I believe that this group will be advisory in nature, which is valuable.

Jaime Yassif: And I believe notwithstanding WHO’s valiant work to expand its capabilities, there’s still a gap between what WHO can do, what their capabilities are and could become in the near future, and what the Secretary-General’s Mechanism can do. What I mean by that is there’s an area in between where if there’s an allegation of an accident… So for example, the Secretary-General’s Mechanism’s authorities do not cover accidents — it’s only allegations of deliberate misuse. Or if you’re just not sure if it was a natural or deliberate or an accident, and you need to run it to ground — you’re not prepared to make an accusation and launch a Secretary-General’s Mechanism, but there’s enough evidence there that you think that something fishy might be going on.

Jaime Yassif: We don’t really have a robust tool right now to address those sorts of questions. So we started our work on this problem in the context of our work at NTI, long before the current controversies emerged. But I think the current challenges highlight this gap and the need to make the UN systems and capabilities more robust to address this in-between zone.

Rob Wiblin: Okay. So just to recap, we’ve got the World Health Organization, and historically their expertise — the thing they’ve done the most of — is investigating natural, new pandemics, where it’s come from an animal or something.

Rob Wiblin: And in principle, you’re saying the International Health Regulations allow them to investigate other things as well, like bioweapons or accidental lab leaks and so on, but at least to date that hasn’t been something that they’ve done very much. So we’re not sure how that would pan out. Then if a state accuses another state of using a bioweapon deliberately, then the Secretary-General of the UN can order an investigation into that.

Jaime Yassif: Correct.

Rob Wiblin: But this means there’s various gaps. So lab leaks — a pandemic where you’re not sure. Was it from a lab? Was it a weapon? Is it a natural pandemic? It’s not clear who’s exactly responsible for figuring that out. And whether anyone in particular could be called on has the expertise necessary to really investigate that and build a global consensus around it. So I guess that’s the main gap that we have. Or are there others as well?

Jaime Yassif: Yeah, that’s right. The way that you’ve characterized it is accurate. It’s not only that we haven’t identified who would be in charge, but also we haven’t identified a process that everyone agrees on for handling this. So that’s basically where we are today. And it’s abundantly clear in my view from the ongoing controversy and the struggles of various countries and the international community to find a clear answer to the question of the origins of COVID.

Rob Wiblin: What’s the potential solution to this, do you think?

Jaime Yassif: This is something that we have been working on at NTI | bio for a while. There’s a concept that we’re developing, which we’ve named the “Joint Assessment Mechanism.” “Joint,” because we think it would be working at the interface of WHO and the UN, and that it would live within the UN System. This would be part of international organizations that already exist — we’re thinking about creating a new mechanism, not a new organization.

Jaime Yassif: We think that it should be transparent. It should be internationally credible. It should be evidence-based and scientifically sound. I think a lot of the features of the Secretary-General’s Mechanism could be applicable here. We’d want a team of investigators that have the right technical expertise, as well as logistic support teams that could be deployed on short notice to wherever their effort is needed. We would need a laboratory network that could analyze samples, conduct analysis, and come to scientific conclusions. It would be defensible and credible in the eyes of the international community.

Jaime Yassif: We’d probably also want to think about when these earlier mechanisms were established, technology hadn’t evolved as much as it has today. And so there are a lot of modern bioscience, biotechnology, bioinformatics tools that we could bring to bear and think on this problem set, and think about whether or not those could help us uncover the truth — either through onsite collection of evidence or through assessment of data that can be collected remotely. There are a lot of questions about how you can bring these tools to bear, and we have a lot of technical work to figure out how to do that.

Jaime Yassif: The other piece here is figuring out where you house it. Would this sit within the UN? Where? Who would be in charge of it? How do you fund it sustainably? How do you make sure it works? How do you establish the authority? So there’s a ton of work to be done. We’re actively engaged in international conversations with partners to figure out the answers to those questions. And we’re really pushing to try to make this a reality, because we think it would be valuable.

Rob Wiblin: Okay. So I’m imagining that I’m a national leader of a country that for whatever reason is considering having a bioweapons program. Basically the problem is that at the moment, although I might worry that if something leaked from this lab and caused a global catastrophe — everyone might figure out that it was me and I’ll get in a huge amount of trouble — I could potentially reassure myself that looking at history, the investigation into where a new pathogen came from might be a real disaster. It might not be organized very well. And so there’s a good chance that no one will figure out that it originated from this country and was my fault. So that might make me more likely to initiate the research program in the first place.

Rob Wiblin: And to plug that gap, we want to create a new Joint Assessment Mechanism, where if we’re unsure where a new pathogen came from — and it’s possible that it’s the result of human action possibly violating the Biological Weapons Convention — then the right people can very promptly look into that and gather the evidence necessary to convince everyone one way or the other.

Rob Wiblin: I guess there’s various design elements that you’re going to have to choose in constructing how this Joint Assessment Mechanism is going to work. Like who triggers it? Do you need to prove anything in order to trigger it? Who chooses who goes onto the investigation committee? Presumably it would be quite contested at the time, as we’ve seen with investigations around COVID. It could be substantially worse if the pandemic was worse. How are you going about choosing those design parameters?

Jaime Yassif: I think you’ve raised some really important questions, and absolutely the design parameters of how this mechanism is established are going to be crucial to its success or to its failure — hopefully the former.

Jaime Yassif: In terms of triggering the mechanism, that is a critically important question and something that we’re thinking about very deeply as we work with our colleagues to shape this. We’ve got to set the bar at the right level. If we set the bar too high and the requirements for triggering it are too onerous, then there’s a risk that this mechanism might never be triggered, even in cases where it would be appropriate to do so or be useful — so we don’t want to have too onerous of a bureaucratic burden.

Jaime Yassif: On the other hand, you don’t want to set the bar too low. If it’s really easy to trigger this, the other failure mode is that you have frivolous investigations triggered for frivolous purposes or political purposes, and it undermines the credibility of it. And then it’s also not useful. So you really want to hit the sweet spot in the middle, and we’re working really hard to figure out what that is. And so that’s a really important question. We don’t have the answer yet, but I agree that that’s really critically important. We have some ideas and so we’ll tell you more when we know more.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I guess that’s the kind of detail that needs to be negotiated between concerned parties. You don’t want to come in with, “It has to be this way.”

Jaime Yassif: Yeah. That’s why we’re working with international partners. I mean, honestly, a lot of this work is 5% inspiration and 95% perspiration. By which I mean, you have idea generation and then you really have to build support for it. And so this is a classic example of that.

Jaime Yassif: And then in terms of the group of experts that get deployed, absolutely we’ve seen recently that that can be a politicized process. I think to the extent that you can define the rules and the experts in advance — so that you’re not making decisions during a crisis — the more likely it is you’ll be able to insulate the process from politics.

Jaime Yassif: So our vision is that you would have a roster of experts that would be determined during peacetime. They would need to be trained. They would need to be certified. They would need to take tests to prove that they’re competent. And that those people ideally would have to have the right scientific and technical skills. They have to understand how to do their jobs and what the standard operating procedures are, and they have to prove that on a periodic basis. And they have to be able to travel to the field in the event that that’s actually part of the process.

Jaime Yassif: If you have this roster of experts in place, in practice you already have a defined list of people from whom you have to choose. And then you can also have established criteria in advance. So you need X people with this set of expertise and Y people with that set of expertise, and you just define as much as you can a priori. So that while there inevitably will be political pressures, we’re hoping to remove some of that and insulate the process from some of that to make it more evidence-based and credible.

Rob Wiblin: Are there any other design choices that you’ve thought about that would have to be figured out if this were taken forward?

Jaime Yassif: I think where the mechanism would be housed is also really important. Our growing feeling is it would be a really good idea to place it under the authority of the Secretary-General. That’s linked to the ability to trigger it, because the Secretary-General has the authority to trigger the UN Secretary-General’s Mechanism, and they are advised by a group of expert advisors. We as a group think that something similar in this case would be useful for a number of reasons. I’m not going to be able to get to all of them now, but one is we believe that that’s a good place for having the right threshold for triggering.

Jaime Yassif: Also, the UN Secretary-General sits in a very high-level position across the UN System and related organizations. And so they are in a position where they could pull together all sorts of different capabilities and resources across the UN System, which would be needed for this kind of process. And they’re in a good position to work with WHO, which is a critical player and has critical expertise. And also the UN Secretary-General just has a lot of credibility, a role that rises above the fray and can work in the best interests of the international community. So politically, it also just makes a lot of sense.

Jaime Yassif: So that’s where we are right now. It’s not set in stone, but that’s the direction we’re leaning, and we feel good about that direction and there’s support for it.

Rob Wiblin: You mentioned that, of course, there’s this existing Secretary-General’s Mechanism, which they can put into action if a country formally accuses another country of having used a bioweapon. As far as I know, that’s never been used for bioweapons, although it has been for chemical weapons.

Jaime Yassif: Correct.

Rob Wiblin: Should we have confidence that that process would be good if we ever were forced to use it?

Jaime Yassif: You mean the Secretary-General’s Mechanism specifically?

Rob Wiblin: Yeah.

Jaime Yassif: I think we, as an international community, should be putting a lot more resources into the Secretary-General’s Mechanism to bolster its operational capabilities. Likewise, they have a roster of experts. They have a network of laboratories. They do run tests and exercises pretty regularly. I do think if tomorrow they were called upon to launch an investigation, they could do it.

Jaime Yassif: But I would have more confidence in their ability to do it if we put a lot more resources into that work. Right now, it’s supported through a variety of voluntary contributions from countries that think this is really important. My guess is we should probably multiply the amount of money that we put into this by five- to tenfold, and it should be a much higher priority. I have a lot of colleagues in the field who I think are doing really important work to strengthen the Secretary-General’s Mechanism. And I’m really grateful to them for the work that they’re doing, and I would love to support that more if I had more time.

Jaime Yassif: The other thing I would say is, generally speaking for these kinds of mechanisms — and this is true of the Joint Assessment Mechanism concept that we are working to develop as well — is that the more that you can regularly exercise and test the mechanism, the more confidence you’ll have in it. And so if we could do really robust, comprehensive exercises to test the efficacy of the UN Secretary-General’s Mechanism and the Joint Assessment Mechanism — if and when it’s created — I think that is the way to have confidence that these mechanisms are effective.

Jaime Yassif: And just going back to your question about design choices. One point that I didn’t stress before that I think is important is that we don’t want this new mechanism that we’re talking about, the Joint Assessment Mechanism, to be a completely isolated pillar that’s fully standalone from what WHO can do and what the Secretary-General’s Mechanism can do. We don’t want to have bureaucratic competition between these different mechanisms. We would love them to be mutually reinforcing.

Jaime Yassif: And if there are resources from these other existing mechanisms that we could build into the Joint Assessment Mechanism, all the better. I think it’s a complicated set of questions that we’d have to answer in figuring out how to do that. But I think there’s a lot of benefit to having these mechanisms be mutually reinforcing. And if in fact by creating this Joint Assessment Mechanism, drawing resources to that work, if that could also in parallel strengthen the Secretary-General’s Mechanism, that would be fabulous. That would be a win-win.

How to actually implement a new idea [00:50:58]

Rob Wiblin: It’s an interesting situation. You’re quite a credible, international organization focused on these issues. And you have this idea for a new mechanism that maybe the UN should put in place to plug this gap in their systems. What steps do you take? Who do you call up? What do you write?

Jaime Yassif: So we have done a couple of international meetings to socialize the idea and solicit feedback, and we bring together a diverse community of stakeholders that can help us think this through. Some of these people are scientists that understand the technical elements and the technical questions we’re trying to answer. Some of them are policymakers and decision-makers who sit in various governments that would ultimately have to decide if they support this. Some of them are people who have a lot of experience working in the UN System, who understand how the UN System works and can help us shape something that makes sense.

Jaime Yassif: There are a lot of different stakeholders we bring together, and we ask them questions. We say, “Well, we would like to do X. What do you think?” And they say either “We support it” or “How about try Y?” That’s an iterative process of soliciting feedback, building the idea, socializing it again, and working to build support. So we’re in the middle of that process.

Jaime Yassif: One of the reasons I have more confidence that we have a good chance of success is we have… So I’m working on this project in earnest, but also working in partnership with Angela Kane, who’s on our team as the Sam Nunn Distinguished Fellow at NTI — she used to be the head of the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs. And so she understands how the UN System works. She oversaw a lot of related work and she has a ton of knowledge and credibility in the international community. And her involvement in this work is really helping us advance this concept, socialize it, and develop more sophisticated ideas. So I just wanted to give a shout out to Angela and to thank her for the work and just to say how thrilled we are to work with her.

Jaime Yassif: In terms of next steps, we have some working groups that we’ve established and that we’re going to launch in the coming weeks. One is focused on technical questions, and one is focused on these policy and institutional questions. So we can dig into some of these key points that you and I have been discussing: How do you design it? What are the design features? How do you establish the authority? And we hope at some point in the future that we can get to a point where we can actually establish the authority and get the critical mass of States Parties in the international community to say, “Yes, we would like this authority to exist and we will vote to support it.” That’s what we’re working towards.

Jaime Yassif: Now is a really interesting political window of opportunity. It’s not an academic question, it’s a very real question that’s at the forefront of a lot of people’s minds. The COVID pandemic has really drawn a lot of attention to these issues and created political space to drive significant change in international biosecurity and pandemic preparedness architecture. We see an opportunity to seize the moment and we really want to go for it, because we think it could make us safer. And so that’s why we’re pushing now.

COVID-19: natural pandemic or lab leak? [00:53:35]

Rob Wiblin: We’ll push on to creating consequences for violators in a second. I’m slightly reluctant to ask this, but people will be too sad if I don’t ask this question. COVID-19 — what do you think? A natural pandemic or might it be a lab leak?

Jaime Yassif: I think the bottom line up front is we just don’t know. My personal view is that it’s most likely to be a naturally occurring event. But I think both hypotheses — naturally occurring or accidentally released — are plausible, and we just don’t have enough information to rule out one or the other. I really hope that we get to the bottom of it, because I think that has value. I’m glad to see the US government and countries around the world pushing to find an answer, but we might never have a definitive answer.

Jaime Yassif: But what I would say is that just the fact that enough people around the world think it’s plausible that there could be a catastrophic global pandemic caused by a laboratory accident, I think points towards a future of what we need to do. If we really think that’s a credible risk, we should be taking much more dramatic steps than we have been taking to reduce the risk that that could happen. Some of that has to do with biosafety strengthening, and some of that has to do with governance of dual-use bioscience research, which I know we’ll talk about in a few minutes.

Jaime Yassif: In terms of how that has shaped our ability to create change, I think it’s a double-edged sword. In one way it has opened up important conversations and gotten people in senior leadership positions to be asking really serious questions about how we safeguard bioscience and biotechnology and guard against these risks, and that’s incredibly valuable. It’s been very interesting to see that and have the opportunity to use the moment to drive change. On the other hand, it’s also created some polarization and some very politicized discourse around these issues, which we find incredibly unhelpful. We’re always pushing to have evidence-based, science-based discussions and to stay away from the politicization, which we don’t think is helpful. So it’s complicated, but that’s how I see it.

Rob Wiblin: What should the consequence be for a country that leaks a terrible pathogen from a military lab or some other secret research lab?

Jaime Yassif: I don’t have an immediate answer to that question. I think the question of accountability for those kinds of events or deliberate attack is a really important one. And I’m not even sure that punitive consequences are the right answer in the case of an accidental release, if there’s not malicious intent or a violation, and if it was just a legitimate research project and there’s been an accident. We should think about whether we should support the country in question or whether punitive approaches are the right ones. So it’s a tough question.

Jaime Yassif: It’s a different matter if there’s an accidental release and it’s found to be coming from a lab that was pursuing bioweapons development. I think that’s a different matter and it seems appropriate to consider the question of accountability and punitive consequences. But I don’t have a clear answer for what that should be. And I think we need to do more work to figure out the answers to those questions.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. As an economist, the thing that jumps to mind to me is the probability of detection multiplied by how bad the consequence would be for a country, if them causing a terrible pandemic were detected. So you’d think if the probability of detection is low, they need to make sure that the consequences are very bad. And I suppose if the probability of catching a criminal, so to speak, is high, then maybe you don’t need to have such a severe penalty in order to make sure that countries are sufficiently discouraged from doing it. I suppose, just in the international realm, it’s hard to think about things like this, because we’re talking about issues of military conflict potentially, or serious conflict between countries. It’s very serious business, rather than just criminal justice policy.

Jaime Yassif: Yeah. It’s hard to divorce the answer to this question from politics, and fundamentally it will be a very political discussion, if and when it does come up. I would say that there are a variety of different kinds of accountability measures that you could think about. Some of them could be financial. Some of them could be diplomatic isolation from the international community. Some of them could be more military. It’s a really tough question to answer, and I think you would want the response to be proportional.

Jaime Yassif: Also, you would want to make sure that you weren’t creating a system that had undesired outcomes or perverse incentives. So you would want to think about that really hard. The other thing that’s worth thinking about also is just the reputational cost to a country. If a significant portion of the international community thinks that they’re responsible for it, even if it’s uncertain, there’s significant cost to international prestige and reputational risks that is in itself a pretty heavy cost, so that’s also worth bearing in mind.

Rob Wiblin: Is there any kind of political policy or legal agenda around this issue of creating consequences for violating —

Jaime Yassif: Not at the moment.

Rob Wiblin: No. Okay. I see. Interesting. I suppose that would be in principle part of the Biological Weapons Convention, but it’s just not, in practice, being pursued at the moment.

Jaime Yassif: Yeah. I just think it’s a really hard question, and one that is not being tackled. And I’ve asked people about it as part of my research, and their answer is generally that it would be really hard to do, and it’s a very political question and it really depends on who were the players involved and what their relationship was to the existing superpowers of the time. Very challenging, but important.

How much can we rely on traditional law enforcement to detect terrorists? [00:58:24]

Rob Wiblin: Okay. We’ve been talking about states here, but turning for a minute to the more traditional terrorist WMD threat. How much can we just rely on traditional security enforcement by law enforcement, intelligence agencies, the FBI, Interpol, and that kind of thing to detect plots to use biological weapons and catch or kill or at least disrupt the terrorists who are trying to do that?

Jaime Yassif: I would love to see a future where I could answer that question in saying, “We’ve got it covered. We can definitely rely on our security community to solve that problem.” I just don’t think we’re there. I don’t think we’ve invested the time and resources to have the tools and mechanisms in place to do that well. I do think now, partially in response to COVID, a lot of these communities are revisiting this question and thinking about bolstering intelligence, bolstering law enforcement.

Jaime Yassif: We also need stronger connections between law enforcement and the scientific community and the public health community, so that they can get better information about what’s going on. I also think a lot of the work that we’re doing at NTI about strengthening governance of dual-use bioscience and biotechnology research and development could help strengthen those tools, and this all needs to be interconnected. Part of the problem is this is a needle in the haystack issue.

Rob Wiblin: Same issue with all terrorism, really.

Jaime Yassif: Perhaps. There’s so much legitimate bioscience and biotechnology research and development going on around the world. And it’s so deeply dual use that it’s very hard to discern malicious intent or malicious action from that mountain of legitimate activity. It’s not that it can’t be done, but we have to set up more effective structures for doing that.

Jaime Yassif: And again, I think the various parts of the security sector that you mentioned all need to invest a lot more resources and capabilities to get us to the future where we need to be. We need to build better tools in the science and technology policy sector and the governance place to enable those security sector agencies to plug into, so we can have a whole system that works. So it’s a really hard nut to crack and it can’t be solved in isolation. I think these other governance approaches that we’re going to talk about in a few minutes are a critical piece, and without that, it’ll be really hard for them to be effective.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, I guess there’s potentially kind of a domestic policy agenda issue that someone could pursue in the US or the UK or Australia, trying to improve the security capabilities to check up on what terrorists are doing or be more aware of what plots terrorist organizations might be pursuing. Is that right? I guess this is more maybe at the national level than the UN level?

Jaime Yassif: I think that there’s both national-level work and international work that could be done. I think individual governments within their respective intelligence and security agencies would need to build up more capabilities to do this work more effectively. Interpol has a really interesting role to play because they are the connecting point for law enforcement and security apparatuses in different countries all around the world. So Interpol also has an opportunity to strengthen their capabilities as well. I think that they are in fact doing that, and I applaud them and we want to support their efforts.

Constraining capabilities [01:01:27]

Rob Wiblin: Okay. Moving on from shaping intent, NTI has a vision for this other comprehensive package of interventions that hopefully collectively can make it a lot harder for anyone to deliberately or accidentally produce or release a really dangerous pathogen. You call this “constraining capabilities,” and I guess it’s what you think is the main thing to do in the case of individuals or terrorist groups or laboratories that are at risk of making a terrible mistake that affects everyone.

Rob Wiblin: I came into preparing for this interview pretty pessimistic that any of this could work. Because my sense is that the technology is progressing so fast that even if you can slow down access a bit, dangerous techniques will ultimately end up being available to people all over the world pretty fast anyway. Maybe to start out, can you tell me why I should be more optimistic that we really can constrain the ability of people to do dangerous things with biotech?

Jaime Yassif: I understand why this is challenging to wrap your brain around. I think a lot of people are challenged by thinking about this in this new way. Part of the reason for that is that the M.O. we’ve seen so far has been very slow movement on the part of large institutions that make decisions slowly — including governments, including international organizations — and they really play a vital role.

Jaime Yassif: I think the way that we need to keep up with rapid advances in bioscience and biotechnology is by partnering with the very organizations that are driving those advances and move at that pace. I think the reason we can succeed is if we are working with the same scientists, and academic research institutions, and companies, and funders, and publishers that are driving the advances — if we build in biosecurity into the very processes by which the technology’s developed — we have a real chance at staying ahead of the curve.

Jaime Yassif: I think it’s a combination of working with these more agile, fast-moving groups, and then it’s also being proactive and not reactive. So instead of responding to a new threat after it emerges and preparing a patch, if we look over the horizon and see what’s coming and proactively build in new biosecurity systems before new capabilities come online, I think we can keep up.

Jaime Yassif: A classic example of this is in the DNA synthesis screening domain. The community of DNA synthesis providers, most of which are companies, voluntarily screen DNA synthesis orders in order to make sure the pieces of DNA — which are the building blocks of all living things, the building blocks of dangerous pathogens — don’t fall into the hands of malicious actors. So they’re pretty technologically sophisticated. They’re able to evolve their screening capabilities as technology advances.

Jaime Yassif: An example of looking over the horizon is benchtop synthesis. That’s this new mode where instead of centralized DNA synthesis, you have this future — which we think is coming soon — where people might be able to print DNA on their benchtop. Not everyone’s going to do that, but a part of the market is going there. What we are thinking about at NTI, and what the benchtop synthesis development community is thinking about, is how do we build in biosecurity by design, and make that a reality before these tools are disseminated widely. That’s a classic example of how you stay ahead of the curve and you don’t let the technology get out ahead of you before the security’s built in. And we need to do that across the board.

Rob Wiblin: So before we get a bit confused, we’re mostly talking here about working with legitimate labs and companies and so on to constrain the capabilities of malicious actors.

Jaime Yassif: That’s right.