Yardsticks: how to compare the scale of different social problems

Note this article was written in 2014 and doesn’t fully reflect our views today.

What are ‘yardsticks’, and why use them?

In order to compare causes, we want to estimate the value of solving different social problems. The problem is, even if we had a precise notion of what counts as ‘value’ (for instance, the amount of human welfare created), it’s not practical to estimate the effect of solving different problems in these terms, especially if you care about the long-run effects of our actions – it’s rarely practical to count how many people benefited from an outcome, or measure how large the benefits are.

This means that in order to compare the scale of different social problems, we need to use rough ‘yardsticks’ of comparison instead. A yardstick is a factor we expect to correlate with the positive impact of solving a social problem (what we really care about), but which is easier to measure.

People use yardsticks (also called metrics, or proximate goals) all the time in other areas when it’s difficult to measure what we really care about. For instance, schools award ‘grades’. These are a yardstick to compare the educational attainment of two pupils, though we know that grades don’t capture everything that matters in education.

We don’t do research ourselves into which yardsticks best track positive impact. However, it’s a major research priority for our affiliates, the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford; the Global Priorities Project, which is part of the Centre for Effective Altruism; and our trustees. We seek to align our views with those of these groups, while also applying some weight to the views of economists and our understanding of what’s regarded as common sense among informed experts.

Any set of yardsticks will embody some value assumptions, and therefore will vary from person to person. In what follows, we outline the yardsticks we most commonly use at 80,000 Hours, attempting to flag the most important assumptions behind them.

Table of Contents

What are the properties of a good yardstick?

For comparing causes, a good yardstick is a property that is both:

- Relevant: increasing the amount of this property correlates with positive impact.

- Measurable: it’s easy to tell, given the resources you have available, whether this property is increasing or decreasing.

Which yardsticks should we use?

To measure short-run impact on welfare

To measure the short-run impact of different actions, we often focus on ‘QALYs’ or ‘quality-adjusted life years’. The QALY is a metric for measuring health that is widely used within health economics. One QALY is a year of healthy life, and can be gained either by increasing the quality of someone’s health or extending how long they live. You can read more about how QALYs are defined here.

Of course, health is not the only component of welfare. Ideally, we’d be able to measure ‘well-being adjusted life years’ or ‘WALYs’. Unfortunately, such a metric has not yet been developed, so instead, we need to consider a patchwork of metrics to capture other aspects of wellbeing. One of the most important is income, though one can also look at life satisfaction, education outcomes, satisfaction of basic human rights, and others.

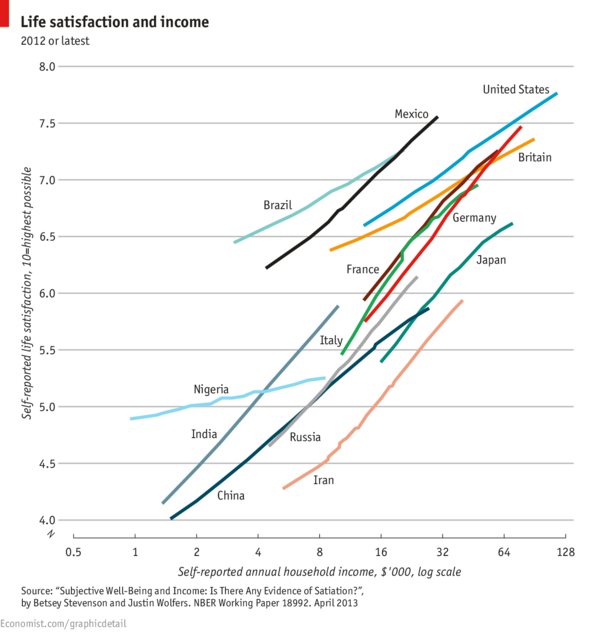

Within income, we prefer to focus on the logarithm of income. It’s widely accepted that there are diminishing returns to the usefulness of income, such that economists often talk about the “law of diminishing marginal utility”. This law means you get more welfare from gaining $100 if your current wealth is $1,000 compared to when your wealth is $10,000. Moreover, it’s thought that the returns are roughly logarithmic, in part due to empirical data, such as that shown in the chart below. There’s some evidence that individual wellbeing hardly increases at all above a threshold of about £50,000, though this has been disputed (for instance see this review paper by Stevenson and Wolfers.

The law of diminishing marginal utility, combined with the belief that all people have equal moral worth, is a key reason many think it’s more important to focus on causes that help the developing world.

We think it’s very likely that the suffering of non-human animals also deserves moral weight (for more justification, see the writings of Peter Singer).This means our yardsticks should also include animal welfare. The main group aiming to compare interventions aimed at animal welfare is Animal Charity Evaluators, who often use the metric of ‘years spent in factory farms avoided’ for different animals. We’re very uncertain how to weigh this metric against QALYs or income.

The importance of the long-run

The preceding yardsticks focused on measuring short-run wellbeing. However, we think the wellbeing of future generations carries moral weight, so we also need yardsticks to measure long-run welfare.

Indeed, we find it plausible that the impact of our actions on future generations is more important than the impact of our actions on short-run welfare, so yardsticks to measure the extent to which we’re putting human civilization on a good long-run path may deserve higher weight than those in the previous section.

To measure long-run impact on welfare

Yardsticks for improving the long-run future need to be distinct from ‘future QALYs’ or something along those lines, because that’s far too hard to measure. Unfortunately, there’s no widely accepted metrics to use as proxies for our impact on the long-run future, but here are our current ideas.

Economists often focus on boosting GDP, or even better, a sustainability-adjusted measure of GDP, such as the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare. For instance, Tyler Cowen has suggested “The Principle of Growth”:

We should make political choices so as to maximize the rate of sustainable economic growth.

Paul Romer has also said:

For a nation, the choices that determine whether income doubles with every generation, or instead with every other generation, dwarf all other economic policy concerns.

We put some weight on this view, because it appears to represent the view of economists, although don’t find the arguments very persuasive, mainly due to the reasons discussed in Chapter 3 of Nick Beckstead’s thesis. In short, because economic growth will eventually end, boosting growth today merely speeds up the point at which this day arrives – a valuable outcome, but not the biggest way we can alter the long-run future.

We’re more persuaded by Beckstead’s view that we should focus on what’s likely to cause positive ‘path changes’ to the future trajectory of civilization. See more discussion of the trade-off between speeding up progress and path changes in this thread.

We think the most important category of these path changes is likely to be ‘existential risks’ – events that could permanently curtail the future of civilization, such as a nuclear war. Nick Bostrom has most famously argued that, if concerned with the welfare of future generations, it’s most important to “maximise the probability of an OK outcome” in the short term i.e. avoid an existential risk.

The problem is that “reducing existential risk” or “causing positive path changes” are still relatively hard yardsticks to measure, so we want a sub-set of metrics that correlate with these but are easier to track.

We’re still highly unsure what these should be, though expect progress over the next couple of years. This means keeping options open is highly desirable, as is investing in more research.

Beyond keeping options open and more research, our best guess is that the most dangerous risks will be human-caused rather than natural, and likely the result of new technology. This position is widely shared by researchers in this area within the Future of Humanity Institute, including Nick Bostrom, as well as others, such as the University of Cambridge’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk. This raises the possibility that speeding up technological progress within the most dangerous areas, without a corresponding increase in our ability to wisely use new technology, could be overall harmful.

What yardsticks are best for measuring reduced chances of human-caused catastrophe? We’re highly uncertain, but suggest the following:

- Level of collaboration.By this we mean extent to which humanity is able to act together to achieve common goals. This is important to avoid dangerous arms races and deal with crises once they arise.

- Level of wisdom. By this we mean the extent to which humanity is able to use our capabilities to good ends, through compromise, reflection, altruism and so on. This is important so that society can spot and take steps to avert potential crises.

- Differential technological development. By this we mean accelerating the development of technologies that are likely to be safe, and slowly down the development of others. Some technologies seem more risky than others, so it would be better if these were slowed down, to allow for the development of other risk-reducing technologies, or the allow time for further gains to collaboration and wisdom.

- Furthering global priorities research. By this we mean further research aimed at working out which yardsticks are best, and which causes are best in light of these yardsticks. This is important because we’re highly uncertain about which yardsticks are best from the perspective of the long-run future, and research on this question is still in its infancy, so further progress would help to work out which projects are best.

- Capacity building. By this we mean effort to increase the resources and ability to coordinate of those who want to mitigate existential risk and improve the long-run future, through advocacy and community building. This is also important because we’re highly uncertain about which yardsticks are best. General capacity aiming to improve the long-run future will be able to take whichever opportunities turn out to be best in the future.

For more, see Chapter 14 of ‘Superintelligence’ by Nick Bostrom, which discusses risks from artificial intelligence in particular but applies to risks from other new technologies. Toby Ord has also written about how to balance capacity building and research against other actions.

Non-welfare values

So far, we’ve focused on yardsticks for human welfare in the long-term. You might think we should put extra weight on factors like ‘justice’ and ‘environmental diversity’ over and above their long-run effect on human welfare, because these factors also have intrinsic value.

We don’t explicitly factor in non-welfare values because:

- There’s less agreement over their importance

- They’re already included to a large degree, because a more just society is also likely one that’s better for long-run welfare.

- It’s unclear how to measure and compare them to welfare.

However, if you would like to add extra weight to a non-welfare value, then you could add them as further yardsticks.

Our overall position

We see the following as robustly good, though difficult to measure, yardsticks:

- Level of collaboration.

- Level of wisdom.

- Furthering global priorities research.

- Capacity building.

We also apply some weight to the following, which are all more measurable:

- Long-term sustainable world GDP growth rate.

- Short-run impact in terms of QALYs, log income, animal welfare etc.

- Differential technological development.

All of the above are relatively high-level yardsticks, so often need to be further divided for practical purposes. For example, the first three yardsticks suggest that “improving institutional quality” and “promoting effective altruism” are good sub-yardsticks.

How robust are our views?

We think that research into which yardsticks are best is still in its infancy, so we anticipate gaining new significant information over the medium-term, which will cause our views to evolve.

This is a point in favour of supporting causes that seem good from many perspectives, and keeping your options open.