Stop worrying so much about the long-term

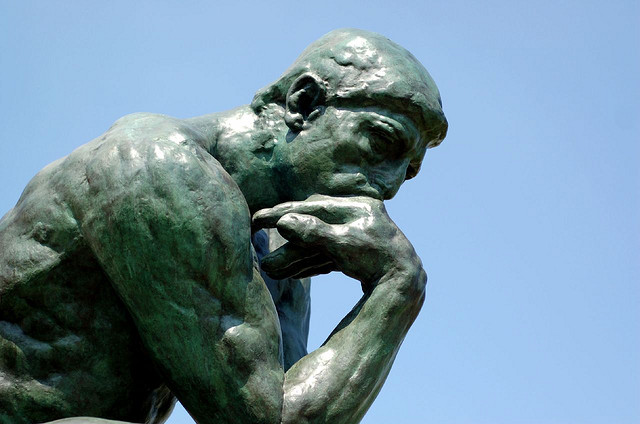

Analysis Paralysis

Today I’ve been reviewing our most recent round of coaching, and something struck me about the applications. Many of them were written by people who were clearly desperate to plan out the next decade of their career, or even their entire working life. As a result, they tended to feel anxious and even overwhelmed by the options available and the weight of the decisions in front of them.

Might this be you? Some giveaways are phrases like “how can I find the right career for me?” or “I’m trying to figure out what to do with my life”.

To people who feel this way, I have this advice: stop worrying so much about the long-term.

Don’t get me wrong, of course your career decisions are important. 80,000 Hours is built around the idea that you can make an incredible difference through your career choices, if you choose carefully.

However, I don’t think that making a detailed career plan is a particularly good way to ensure that your career goes well in the long-term. A better idea, especially at the start of your career, is to make sure you get the next step right: focus on getting into a better position, and then worry about what comes next when more decisions arise.

This may sound counter-intuitive. So why do I recommend it? Four reasons:

1. You have limited knowledge

If you’re at the start of your career, then you probably don’t know much about the career options available, and how to make a difference in the world. It’s also very difficult to know which jobs you’ll enjoy most and be best at before you try them out.

Given these facts, at the beginning it’s much more important to focus on exploring than setting off down a career path. It makes more sense to make a long-term plan after you’ve explored your options.

2. Planning too much can make you inflexible

Setting yourself goals can help keep you motivated and interested in the work you’re doing. However, research also shows that setting goals can narrow your focus and inhibit learning.

It’s important to stay open to new opportunities and to be receptive to new information, and one way to do this is to keep your long-term plans broad.

3. The future is really hard to predict

This is the kicker: It’s very difficult to know what career opportunities will be open to you in five years time. The world changes, and your situation in the world changes as well.

Moreover, you are likely to change: your values, your preferences and the causes you think are important. Consider just how different your priorities were five years ago. It might well be the case that in five years time you will simply want a different career. we consistently underestimate how much we'll change</a>. Quoidbach, Jordi; Gilbert, Daniel; Wilson, Timothy. "The End of History Illusion." Science. 2014-12-05.</p> " rel="footnote" class="footnote-link no-visited-styling" aria-label="Footnote">1

The result is that any plans you make now are likely to get completely overturned in the medium term, so time spent planning could easily end up wasted. Even worse, you could find yourself hemmed in and have difficulty altering your plans when the situation changes.

4. You don’t have to commit to one path

Careers have become far more flexible in the last couple of decades. Most people work in a variety of types of job over their lives, and it is no longer expected that you will stick with one profession or company for your entire life (with certain exceptions such as medicine and academia). Long-term planning is less necessary than ever before."planned happenstance"</a>. Kenneth F. Hughey (2009), "The Handbook of Career Advising" (Jossey-Bass).</p> <p>A textbook on organisational psychology lists some of the key trends in career choice, and includes: "More short-term contracts", "increasingly frequent changes in the skills required in the workplace", and "individuals should be flexible in terms of the work they are prepared to do." The book also outlines how the concept of a "boundaryless career" has "gained a lot of momentum and attention in career theory and practice" since the 1990s, and that "bureaucratic careers" - characterised by predictable advancement within a single occupation or organisation - are becoming less common.<br /> pp 596 - 602. Arnold and Randall, "Work Psychology: Understanding Human Behaviour in the Workplace", (2010), 5th Edition, Pearson Education Ltd</p> " rel="footnote" class="footnote-link no-visited-styling" aria-label="Footnote">2

So what should you do instead?

Especially if you’re at the start of your career, try not to worry too much about what you’re going to do long-term. Instead, focus on making your next decision. For instance, if you’re about to graduate, ask yourself “what job should I take after I graduate?” rather than “what should I do with my life?”

This is why we mainly focus on your next step in our coaching and how to choose process.

The best way to take account of the long-term is to focus on taking a step that will improve your career capital and help you learn more. That way, you’ll put yourself in a generally better position, allowing you to choose better options in the future.

If you’re right at the start of your career, this is probably all you need to do. However, I think most people should have an eye to the long-term even if it’s not their main focus. There’s a sense in which it’s true that “a bad plan is better than no plan”.

We think the best way to do this is to have a vision – a broad goal for the direction in which you’d most like to travel over the next two to ten years. This provides a sense of direction and motivation, without being overly specific and narrowing your focus. You can then make your vision more and more detailed as you get older and learn more.

There are also occasions when thinking about your vision is necessary for deciding on the next step. For instance, whether or not you want to be a doctor in the long-term is the major factor in working out whether or not to go to medical school. In these cases, it’s good to think about the long-term because you’re doing it in a focused way that relates to a real decision, rather than getting lost in a jungle of possibilities.

Conclusion

Getting used to this way of thinking takes time. Living with uncertainty can cause some anxiety, and it’s tempting to try to get your career “all figured out” so you can stop worrying about it. But unfortunately, for the reasons set out above, that approach comes with a number of hazards.

Instead, the better approach is to focus on each decision as it comes, enjoy the freedom of not having to decide your life at age twenty (or forty!), and take comfort from knowing that if each step makes sense, you’re doing the best you can to build a successful and impactful career.

Notes and references

- In general, people’s interests and personality change a lot overtime, but we consistently underestimate how much we’ll change. Quoidbach, Jordi; Gilbert, Daniel; Wilson, Timothy. “The End of History Illusion.” Science. 2014-12-05.↩

- “The Handbook of Career Advising” aims to sum up the consensus in the literature on career advising best practices. In Chapter 2, “The Evolving Workplace” it sums up how the structure of jobs has changed in the last few decades. Two of the major trends it identifies include: (i) higher pace of change (ii) jobs becoming more flexible. It recommends advisors encourage advisees to focus on taking an entrepreneurial approach to their careers, acknowledge uncertainty is unavoidable, and attempt “planned happenstance”. Kenneth F. Hughey (2009), “The Handbook of Career Advising” (Jossey-Bass).

A textbook on organisational psychology lists some of the key trends in career choice, and includes: “More short-term contracts”, “increasingly frequent changes in the skills required in the workplace”, and “individuals should be flexible in terms of the work they are prepared to do.” The book also outlines how the concept of a “boundaryless career” has “gained a lot of momentum and attention in career theory and practice” since the 1990s, and that “bureaucratic careers” – characterised by predictable advancement within a single occupation or organisation – are becoming less common.

pp 596 – 602. Arnold and Randall, “Work Psychology: Understanding Human Behaviour in the Workplace”, (2010), 5th Edition, Pearson Education Ltd↩